More than US$ 800 million has been invested in the construction of the Mariel Special Development Zone and in the renovation of its wharf. Nevertheless, the investment has not been enough for this ambitious project—a potential new motor for the Cuban economy—to come through. Fear among investors of renewed economic restrictions imposed by the United States, local administrative incompetence by the armed forces—who would oversee the project—, the internal obstacles of a system that does not promote market economy, and the millions of dollars owed to Brazil have flooded the project.

By Suchit Chávez for CONNECTAS

Raúl Castro takes Dilma Rousseff by the arm to walk the few steps that separate her chair from the podium. For a moment, Rousseff, President of Brazil, wonders on what side of the ribbon she should stand. Smiling, she gives the scissors to Castro, President of Cuba, so that he cuts the ribbon. Everyone applauds. It was January 27, 2014, and the first phase of the Port of Mariel project was being launched in Cuba against the backdrop of the second meeting of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC).

From the podium, Rousseff greets her counterparts: Nicolás Maduro, from Venezuela, and Evo Morales, from Bolivia. During her speech, she mentions several businessmen, including Marcelo Odebrecht, president of the eponymous company and responsible for the construction work, and Luis Alberto Rodríguez López, president of the Cuban company Grupo de Administración Empresarial (GAESA), tasked with the administration of the Mariel Special Development Zone (ZEDM). At the end of the speeches, the cranes began to load the first containers in the renovated port area. It was a great celebration. With an investment of US$ 862 million from the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) of Brazil, the renovation of the Port of Mariel and its neighboring special economic zone was beginning to take shape.

Five years later, the situation of the protagonists of that celebration could not be more different. Odebrecht is serving a 19-year prison sentence for transnational corruption after it was made public that his company had paid over US$ 3,500 million in bribes to be awarded contracts in the region. Rousseff was removed from office. Maduro is no longer recognized by fifty countries as President of Venezuela. The deals of the BNDES are being brought into question, and the Bank is being investigated for financing multimillion dollar projects that, according to the inquiries, have benefited only construction companies. GAESA is among the companies on which the US State Department has imposed business restrictions. Lastly, the operational capacity of the Port of Mariel and the ZEDM is very limited, as shown by the balance sheets of the companies operating in the area.

The project, which, according to Castro, is “the largest investment made by the Cuban Revolution in the last 50 years,” has had many obstacles. These include fear among investors due to the renewed commercial restrictions imposed by the United States under Title III of the Helms-Burton Act; slow management of investment processes; a depressed local economy that since the socialist era has not managed to catch up with the pragmatic principles of capitalism; and, now, the complaints of the main financier of the work, BNDES, which due to the new ideology adopted by the giant of the south—no longer as generous as before—, demands that Cuba honor the agreements that made it possible to make the investment.

The ZEDM was created and approved by the Council of Ministers on Decree 313 of September 2013. It was one of the strategies to “update the Cuban economic model.” Operations started after the renovation of the Port of Mariel, where millions had been invested since 2009. Located to the north of the province of Artemisa, 45 kilometers to the west of Havana, the ZEDM has a total area of 465 square kilometers.

According to a document review carried out by CONNECTAS for this investigation, by March 5, 2019, the records of the ZEDM showed 43 investors. These included 6 Cuban companies—one of which had been incorporated as an International Economic Partnership—, 24 foreign companies, and 12 joint ventures (partnerships between a Cuban and a foreign company). Of all these companies, only 19 were “in operation” and the rest “under investment process.”

The table below shows detailed information about the companies that have been approved as investors. It includes line of business, country, approval date, and other data.

As stipulated by Decree Law 313, the ZEDM, as published on its website, seeks to diversify and breathe life into the Cuban economy. Despite the advantageous offer of implementing a zero-tax policy on profits from sales and services, labor force, and customs duties, for 10 years, the investments have not yielded the desired results.

Of the 19 firms “in operation,” four are Cuban. Since 2014, dozens of publications in the official media have stressed that foreign investment attracted by the ZEDM exceeds a billion dollars. If this figure were solely based on the value of businesses approved as operators, it would be accurate. But the reality depicted by the balance sheets of some investors is different. Some report allocating only up to US$ 700,000 to their Cuban operations.

For this investigation, we tried to arrange interviews with the officers in charge of the ZEDM. To this end, we contacted the Press Secretariat of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the ZEDM Office, and the Cuban diplomatic representation in Central America, but they never responded to any of the questionnaires that we sent.

Is the Money Flowing?

For this investigation, CONNECTAS reviewed documents and the latest balance sheets submitted by 14 international firms “in operation.” Of these, some are global corporations that did not provide a detailed breakdown of their assets. Unilever, a British-Dutch company whose subsidiary Unilever Suchel has operated in the ZEDM since June 2016, is a case in point; its latest yearly report, published on its website, only mentions that they have a subsidiary in the ZEDM. Other corporations that did not provide a detailed breakdown include CMA CGM LOG, from France; China Communications Construction Company Ltd, from China; and Bouygues Construction, also a French company.

We were unable to obtain the balance sheets of Engimov Caribe, from Portugal, because the information cannot be remotely accessed. We only acquired data on yearly sales, which amounted to US$ 9.4 million. Another six companies openly disclosed their investments in Cuba. Yet others, despite having received authorization to operate there, did not even acknowledge carrying out activities on the island.

One of the latter companies, Tecnologías Constructivas (Teconsa), is a joint venture constituted by a Cuban firm, Simen Aut, and a Spanish corporation, Estructuras Titán Steel. This joint venture was authorized to operate in Cuba in January 2016 and by November of that year, its top management was talking about an initial investment of US$ 13 million.

In its 2017 year-end balance sheet, Estructuras Titán Steel stated that total assets and liabilities amounted to US$ 5.1 million. The balance, however, does not reflect the company’s investments in Cuba.

Resa Caribe, an international subsidiary of the Spanish company Euro Resa, received the approval to operate in Cuba in December 2017. That year’s balance sheet—the last one available to the public—includes only one statement about its investment in the country, in the section “Evolution of the Company.” Its financial report merely reads, “Continue to foster development and international expansion. Startup of Resa Caribe (Cuba) and Resa Perú. Creation of the International Development Department.”

A joint venture, Logística Hotelera del Caribe, received its approval to operate in the ZEDM on December 15, 2016. It is a subsidiary of Iberostar Hotel & Resorts, based in Spain, and its Cuban counterpart is AT Comercial. Iberostar, as stated in its balance sheet, owns 70% of Logística Hotelera.

By December 31, 2017, the net worth of Logística Hotelera del Caribe was € 5.1 million but in its balance sheet, in the section “Distributed Dividends,” there was no statement whatsoever. Iberostar has invested in Cuba for a long time. Before having access to the ZEDM, it was already doing business through three other subsidiaries—Cubacaribe Hoteles (50% share), Costa Varadero (50%), and Trinidad Hoteles (50%)—, as stated in its 2017 balance sheet. Furthermore, the website of the company mentions that it runs 20 hotels in different parts of the island. According to information published on the ZEDM website, Logística Hotelera del Caribe is a provider of custom-made inputs for the hotel network in Cuba.

Since the Internet Industry is still fairly new in Cuba—and due to a long-standing lack of transparency in the country—, there is a dearth of official commercial data. Nevertheless, the Center for the Promotion of Foreign Trade and Investment (Procuba) has recently released publications regarding the Commercial Directory of the country. This official document includes information about numerous corporations established on the island. Several that are associated with the ZEDM, however, are not mentioned.

One of the few Cuban companies that are associated with the ZEDM is AT Comercial, which is mentioned in the Directory. The document also specifies that Gaviota—a company administered by and belonging to the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (MINFAR)—is the governing entity or Higher Organization of Business Management (OSDE) of AT Comercial. This situation has had a direct negative impact on the efforts of those who wish to attract foreign investment to the island due to the restrictions imposed by the United Sates on the companies linked to the MINFAR.

Among the “oldest” users of the ZEDM are two subsidiaries of BDC International, a Belgian company. These are BDC LOG Transporte y Logística and BDC TEC, both operating exclusively with foreign capital. The former provides logistic and transportation services, while the latter works in electronics. They were approved for operation in April and May 2015, respectively.

According to their 2018 balance sheets, the net results of BDC LOG amounted to € 99,686 and those of BDC TEC to € 1,164,762. Assets reported by BDC International, the Belgian parent company, amounted to € 57.7 million for 2018.

Another one of the oldest tenants at the ZEDM is Profood Service, which obtained the required approval in March 2017 and operates as a foreign capital company. It is a subsidiary of Spain-based Hotelsa Alimentación. This company, as stated in its 2017 balance sheet, reported having a 99% share of Profood and a net worth of € 76,012.39 with a negative result of minus € 57,327 for the business year. In addition, in the two bank accounts of the company in Cuba, the funds were US$ 508,703.

Hotelsa is a manufacturer and distributor of food products for hotels. Its 2017 balance sheet showed that its total assets were nearly € 24 million. Besides Spain and Cuba, the company has presence in Morocco, Cape Verde, Tunisia, Portugal, Sri Lanka, and Mexico. Based on the same balance sheet, it also had negative results in Morocco and Mexico at the end of the year.

Despite being one of the oldest users of the ZEDM, recently, in February 2019, an official publication reported that the company had become productive four years after receiving the approval. “After completion of the investment process for the plant, Profood Service, a Spanish capital company, started operations this month of February.” The publication added, “It is expected that at peak production capacity, its catalogue will include over 300 products and the plant will produce around 26 million units every year.”

Financial Restrictions

American federal regulations on money and financing have specified a series of restrictions for Cuba to avoid funding the MINFAR or any other institution associated with the Cuban armed forces. In accordance with this logic, the US State Department regularly publishes and updates a list of entities and sub-entities identified as linked to the MINFAR either directly or through the companies and holdings that the Ministry controls, including the ZEDM.

US legislation prohibits all American citizens and entities from conducting business or financial transactions with listed companies. The only transactions that are allowed are those that predate an entity’s inclusion in the Cuba Restricted List.

The list does not specify the date when the ZEDM was included. Nevertheless, at least in 2007, it was already identified as a sub-entity of GAESA (Grupo de Administración Empresarial), led by Luis Alberto Rodríguez López, former Raul Castro’s son-in-law and a guest of honor at the inauguration of Stage I of the Port of Mariel project. Official data provided by the Cuban Statistics and Information Office (ONEI) showed that GAESA was administered by the MINFAR but it does not specify whether the ZEDM is under its jurisdiction.

Banco Sabadell, the international Spanish counterpart of Financiera Iberoamericana, is a joint venture that was approved to operate in the ZEDM in September 2016. The Cuban side of operations is overseen by the Foreign Trade Bank of Cuba. During this investigation, we were not able to corroborate whether Sabadell was an exception on the restricted list. We tried to contact them via email to determine how they deal with the risks associated with their international investments but at the closing of this publication, no reply had been received.

According to its 2017 financial statement, by the end of the year, Sabadell had a 50% share of Financiera Iberoamericana and its capital amounted to € 38.2 million, with total assets of € 81.4 million. The document also states that only € 747,000 in dividends was paid in 2017.

Financiera Iberoamericana received the approval to operate in the ZEDM in September 2016. Interestingly, Banco Sabadell had canceled operations on the island only three years before. Press reports reported that in 2013, the Spanish bank had requested that the license granted to the Caja de Ahorros del Mediterráneo (Mediterranean Savings Bank) be revoked in Cuba, a business it had acquired two years earlier. No public press release explained the reason for this. Nevertheless, a year after the potential flexibilization of commercial relations between the United States and Cuba, according to the above press reports, Sabadell was considering its return to the island.

Moreover, there were also press reports stating that the incorporation of Financiera Iberoamericana as a joint venture—with Sabadell as its counterpart—was completed in 1999. This process took place with the participation of Grupo Nueva Banca (Cuba) and Natcan Holding International, a subsidiary of a Canadian bank.

Banco Sabadell is the more conspicuous name in the Sabadell Group. This business conglomerate consists of 130 globally integrated enterprises and 30 companies using the equity method of accounting. The Sabadell Group invested € 19.1 million in Financiera Iberoamericana, according to its 2017 balance sheet.

With a business volume of over € 5 billion yearly and total assets of € 221 billion in 2017, it is not surprising that the Sabadell Group has presence and more than a thousand offices in many countries, including the United States. The balance sheet does not specify the number of bank accounts and the volume of transactions of the Group in the United States. Moreover, the 2017 balance sheet does not include Cuba in its breakdown of representations and offices as a country associated with its financial activities.

Another company with foreign capital that has been authorized to operate at the ZEDM, TGT Caribe, also had problems at startup. This company is a subsidiary of the Spanish TGT Ultramar Overseas and is still “under investment process.” The approval to operate in the ZEDM was granted in November 2017. TGT Caribe will produce dairy products.

The 2017 balance sheet of TGT Ultramar Overseas states that it was established in 2016 and has several subsidiaries in Spain. Although TGT Caribe is referred to as a member of the group of companies authorized to operate in the ZEDM, it still owed TGT Ultramar Overseas € 2 million that year.

Not a port of exit

The Port of Mariel, located in the ZEDM, cannot be considered a lifesaver for the Cuban economy. Emilio Morales, president of the Havana Consulting Group, a consulting firm based in Florida that provides financial advisory services to companies interested in investing in Cuba, claims, without giving further information, that “ships [departing from the Port of Mariel] leave empty; Cuba exports almost nothing.”

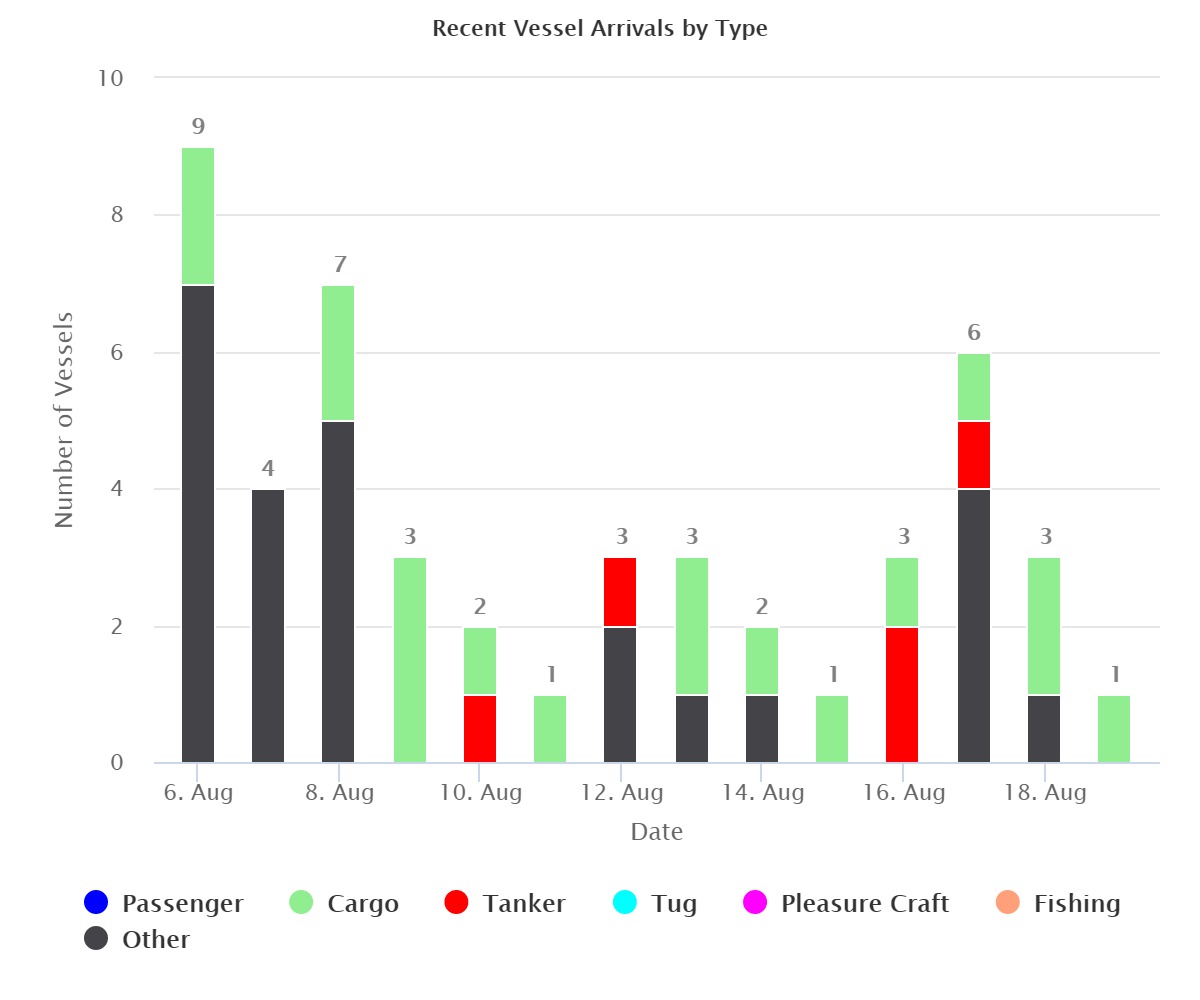

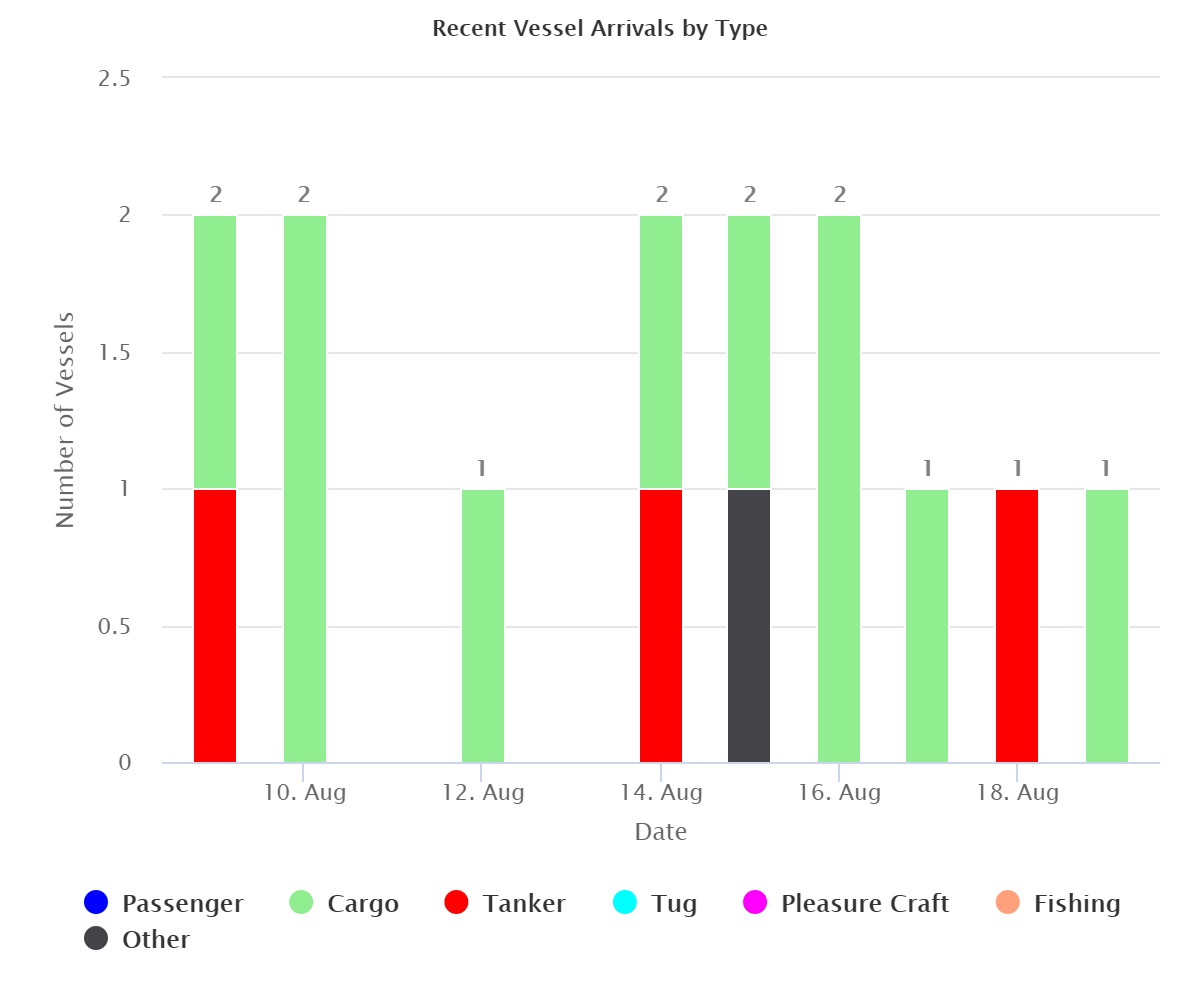

Morales’s statement is consistent with data provided by marine monitoring tools, such as Marine Traffic. They show that arrivals and departures of cargo ships are not frequent.

Last August 21, according to Marine Traffic, there were 33 ships at the Port of Mariel. Nevertheless, most were Cuban (28) and several had not undertaken any recent activities. In fact, some ships seemed to have been anchored there for months.

Despite the above information, official communiques have stated that the Port of Mariel is currently one of the main commercial sites on the island. Although arrivals are infrequent compared to other Cuban ports, the level of activity at Mariel is higher.

The financial complexities of Cuba—and their potential solutions—have been analyzed by William LeoGrande, a political scientist with a PhD from the University of Syracuse. LeoGrande is a specialist in foreign policy and a scholar of Cuban history. Unknowingly, he used the same language as the balance sheets: so much excitement about new investors and so little transparency in execution. “I believe that the data on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) provided by the Cuban government are reliable in general but they tend to focus on new agreements rather than capital flows. Moreover, the government rarely talks about agreements that never happened or about companies that decided to leave.”

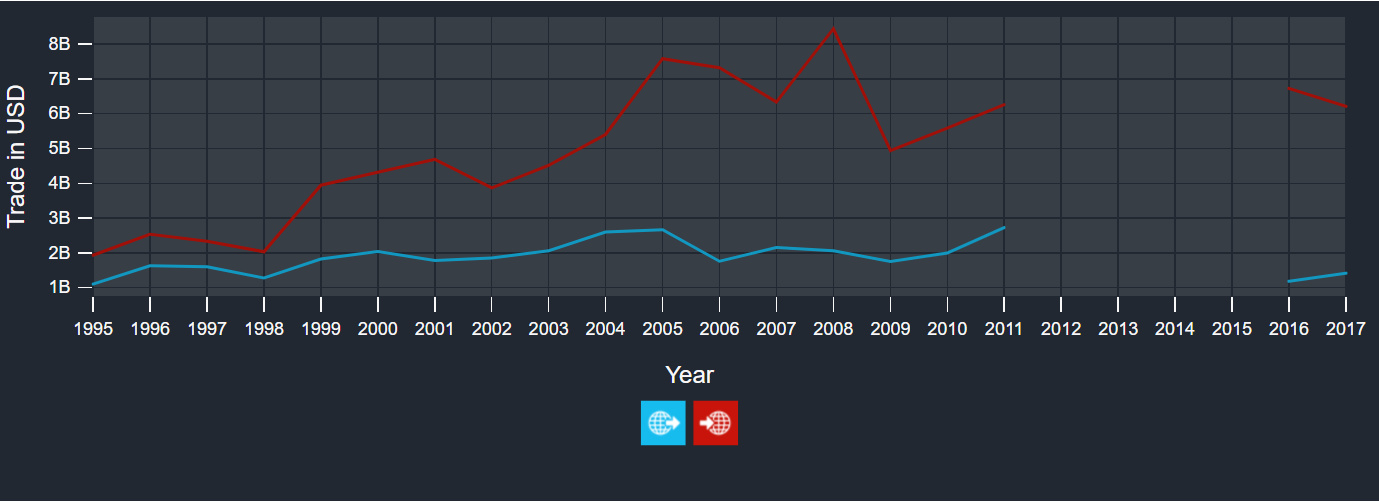

The descriptions of the experts are in line with the data produced by the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), a tool developed with the support of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab. It has analyzed global commercial data using the information in the trade statistics database created by the United Nations (UN Comtrade). The OEC shows that Cuban imports have grown faster than exports.

Although there is no information about some years, the statistical behavior does not show a consistent difference after the ZEDM was inaugurated in 2013. In other words, despite major reforms, such as the passage of two laws on foreign investment, and a project such as the ZEDM, the dependence of Cuba on exports rather than domestic production to satisfy its needs has not changed. On the contrary, the island’s economy has been driven basically by a larger volume of imports.

For Emilio Morales, another problem that has stopped the ZEDM from taking off is that investors are not free to hire their own staff. That is, there is excessive bureaucratization. According to the official website of the special zone, they are required to approach certain Cuban companies to recruit the personnel necessary to operate and comply with the 2014 Law on Foreign Investment. The law states, in Article 30.1, that staff should be hired through a state intermediary. The result is an internal structural obstacle that unsuccessfully tries to provide a solution to capitalism based on socialist tenets.

In terms of job creation, it is not easy to compare the ZEDM to other areas. The ZEDM’s official website claims that the project has created 6,850 direct jobs. Nevertheless, there is no breakdown to determine whether the number of jobs referred to by Odebrecht in its balance sheets—which no longer exist and are associated with construction work and the expansion of the Port of Mariel and the ZEDM—was 2,435 at the completion of the works.

CONNECTAS tried to contact all the companies via email. The objective was to interview them on the subject and obtain further information about their balance sheets and trade relations with Cuba. At the closing of this publication, no company had responded to our requests.

In the Shadow of Odebrecht

The plan to finance the ZEDM was based on proposals from other countries, including Venezuela. In addition, as the result of the cooperation agreement with Brazil, Cuba was offered lines of credit at low interest rates, which were tied to Brazilian exports. These transactions required an agreement between three parties: The National Bank of Cuba, the debtor; the BNDES, the financier; and either Compañía de Obras e Infraestructura (COI), a subsidiary of Odebrecht, or Ingeniería del Transporte (TRANSPROY) as the guarantor and beneficiary that would export all the inputs necessary to execute the project. The funds were transferred directly from the BNDES to COI, and the contracts were based on the cooperation agreement between Brazil and Cuba, in effect since 2008.

Audit TC/034.365/2014/1 of the Court of Accounts of Brazil establishes that Cuba financed engineering projects for US$ 848 million loaned by the BNDES. Of this amount, US$ 831 million was paid to Odebrecht and the rest to TRANSPROY.

The audit report, however, does not provide a clear account of potential irregularities by the Cuban entities. It only points out their noncompliance with the bidding process. The Court of Accounts explained, “Though the island had no legal instruments to enter the bid, the BNDES should have informed, before granting the credit, that in Brazil the process is mandatory.”

Last July, El Nuevo Herald prepared an interesting investigative report. The information brought to light that the relationship between Cuba and Odebrecht is recorded in “Drousys,” a secret accounting system hosted in servers in Switzerland and operated by Odebrecht’s Structured Operations Division, which is responsible for managing and paying bribes worldwide.

In the words of the Herald, “In the more than 13,000 documents stored in Drousys are references to a payment in the amount of $8.44 million. The payment is also mentioned in a document with the English phrase ‘Mariel Port Cuba Conquest’ in the title.”

The Herald admits, however, that the destination of the money is unclear as are the multiple references to Cuba in Drousys. “We may never know if Cuban officials received bribes or not,” explained the newspaper that put together the collaborative investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists of the Lava Jato case.

In addition to the above, other political changes have had negative impacts. In December 2018, a delegation of nearly 8,000 Cuban physicians who were working in Brazil under contract were dismissed. Thus, Cuba stopped receiving a millionaire income. At the same time, the current President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, requested an investigation on the credit granted by the BNDES to Cuba. Amid all this, Bolsonaro, as published by The New York Times last June, had not managed to find replacements for the Cuban doctors.

The heart of the matter is Cuba’s failure to repay the loans granted by the BNDES for the development of the ZEDM and the renovation of the Port of Mariel. Several media have informed that the total outstanding debt may be nearly US$ 580 million.

Based on data published in its annual reports, Odebrecht decided to drastically reduce its presence in Cuba after the completion of work at the Port of Mariel and the ZEDM.

Rough Seas at the ZEDM

“The Cuban government did not take advantage of the opportunity created by the opening promoted by Barack Obama. It is evident that Cuba’s glamour as an investment destination has dropped to a minimum.” This argument was put forward by Emilio Morales to explain why Cuba has had modest success in attracting investors to the ZEDM, as published in a column in June 2018.

In the above statement, Morales referred to the beginning of the normalization of relations between Cuba and the United States, an endeavor that started in 2014 and ended in 2016 with the visit of former American President Barack Obama to the island. During a public appearance, Ana Teresa Igarza, then director of the ZEDM, explained the investment opportunities available. For him [sic], “The Mariel Zone project is almost dead. This is because of the circumstances, of the implementation of the Helms-Burton Act. It didn’t manage to attract investments before, let alone now.”

Morales, a Cuban national who has taken up residence in the United States since 2007, also talked about the coming into effect of Title III of the Helms-Burton Act on last May 2. Enforcement of this Title had been repeatedly postponed by several American presidents. Donald Trump, however, has endorsed its implementation. Title III allows Cuban citizens residing abroad or foreign companies whose property was confiscated in 1959 to sue for damages in the American court system. Nevertheless, the main requirement for legal action is that an individual or entity is profiting from their property. “Businesses are very cautious,” Morales said. “No one will risk investing.” According to William LeoGrande, another expert consulted for this investigation, this is an indirect negative impact that is practically driving away potential investors.

For LeoGrande, “The Cuban economy is definitely suffering because of the new economic sanctions imposed by the United States and the decrease in oil shipments from Venezuela. Basic consumer goods are scarce, and fuel consumption is being restricted by state-owned companies. The private sector has been especially affected by American sanctions, particularly by the ban on educational trips to Cuba, known as “people to people” exchanges, and on cruise ships.”

“The ZEDM makes sense as a way to attract FDI (foreign direct investment). Nevertheless, it has important limitations, including the poor infrastructure that surrounds the Zone and the overall difficulties facing foreign investors that wish to do business in Cuba. Moreover, enforcement of Title III of the Helms-Burton Act will further discourage new investors,” LeoGrande wrote in an email. According to him, the administrative delays in repaying the investments made in the ZEDM are not the only problem, as evidenced by the postponement of operations by some investors.

The damaging effects of the enactment of Title III of the Helms-Burton Act have already been observed. In early August, the Meliá hotel group reported a 10% loss in revenue in the first semester of 2019 in Cuba, where it has more hotels—a total of 36—than in any other country where it operates, according to its webpage. This is partly due to the ban—imposed by Trump last June—on cruise ships journeying to the island.

Press reports show that there are indications that even established firms, such as Banco Sabadell, are taking steps to leave the island due to the hardening of the sanctions.

As for Morales, he refuses to blame the American restrictions for this situation. Morales explained that up to now the lack of success of the project “has nothing to do [with the sanctions]. It’s the government’s lack of strategic vision.”

Morales did not provide information on the above but his opinion is consistent with what the data suggest in the balance sheets. That is, operations are yet to set sail. “The approval has been signed but things haven’t moved an inch. Very few investors are in the stage of construction,” he added.

There is no sense of immediate improvement. According to LeoGrande, “Cuba is likely to have a small recession this year due to the marked decrease in tourism caused by the US travel restrictions, the drop in cheap oil shipments from Venezuela, and the loss of income from the medical missions in Brazil.”

This academic believes that the project is still feasible but that a strategy to save the ZEDM is needed. This may include improving the physical administrative infrastructure for foreign investors because “Cuba cannot do anything about the US sanctions.” For Morales, in turn, the solution lies elsewhere: liberalize the market and allow investments from Cuban individuals—private citizens and residents in the island and abroad.

One thing is certain. The Cuban state has started to shift to a more liberal economic policy, just as Morales and LeoGrande observed. The 1995 Law on Foreign Investment stipulated a 30% tax on profits for joint ventures, foreign companies, and foreign partnerships. By 2014, when the new law was enacted, the tax was reduced to 15% and a grace period to pay it was established for the first eight years of operation.

The above notwithstanding, measures have been slow in coming to push forward the so-called “largest investment of the Cuban Revolution.” This project, according to available data, languishes docked in a port and there is no good weather in sight to set sail.

Below you can find the financial statements of the following companies: