04.The assistentialism that bolted allies in

Funds received in several countries enabled exporting the so-called 21st Century Socialism and the creation of political parties that were served with questioned social programs. Despite the multimillion resources spent, sustainable benefits were not gained and with oil prices drop, the vulnerability of the model was evidenced.

Daniel Ortega, President of Nicaragua, listened pleased when Jorge Arreaza, Foreign Minister of Nicolás Maduro administration, stated in Managua that Venezuelan revolutionaries were willing to spill blood to protect Nicaraguan sovereignty and independence. The offering, rhetorical or not, could be considered as an addition to a concrete aid made available to the National Liberation Sandinist Front (FSLN) president in the last decade: Oil loans from the Venezuelan government let him have over 3,760 billion dollars for social and socially productive projects, according to Nicaraguan Central Bank (BCN) data.

Credit flow, although lower after the hydrocarbon boom, has not disappeared even when the South American country is enduring the worst economic and social crisis in its history; the Human Rights Council of the United Nations in an unprecedented resolution, urged Maduro to accept international humanitarian aid for his fellow countrymen in September 2018.

Arreaza delivered his speech two months before, just after the second quarter had ended. In that period, the Venezuelan government delivered a 9.2 million-dollar loan to Nicaragua, a modest figure that was part of the multimillion flow that turned the president into a privileged Maduro’s ally, as well as his predecessor, the late Hugo Chávez, who have provided him an economic base that enabled him to become politically strong thanks to the discretional management of the social aids.

“President Daniel Ortega, you need to know that if the Bolivarian people, the revolutionaries of Venezuela, had to come to Nicaragua, to defend Nicaraguan sovereignty and independence, and offer our blood for Nicaragua, we would go as Sandino did, to the mountain of Nueva Segovia” — words of Jorge Arreaza, Chancellor of Venezuela

The first boost within that strategy, that allowed Caracas governors to earn a loyal diplomatic partner, took place when Ortega was still a candidate running for president in 2006. FSLN former commander had been President of the country between 1980 and 1990 but had not been able to regain power after three tries. Seven months before the November election, he was Chávez’s guest of honor at Miraflores Presidential Palace in Caracas during the signature of an agreement between PDV Caribe, a Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), and Nicaraguan Municipality Association (AMUNIC), controlled by Ortega’s party. The agreement allowed sending 82,000 diesel gallons to Sandinist mayors, to be distributed among transporters, farmers, and ranchers four week before the election.

The operation was achieved through Alba de Nicaragua company, founded at that event as a partnership between the oil company and the municipalities. The company had the objective to be the local representative of Petrocaribe, the flag cooperation program that sells oil through preferential credits in the Caribbean and Central America. The agreement was the beginning of a support strategy that took the administration of the controversial Nicaraguan president Enrique Bolaños to report before the Organization of American States (OAS) a Venezuelan “interventionist challenge” and “vote buying”.

Daniel Ortega received in 2006 support from Venezuela for his candidacy for the presidency of Nicaragua. Those who denounced the support said that a "purchase of votes" was organized from Caracas / THOMAS STARGARTHER, LA PRENSA NICARAGUA

The Nicaraguan example is far from being an exception in a region where Venezuelan oil credits helped launching new candidates or securing in power political Chávez and Maduro’s allies. Evidence collected in this #Petrofraude journalist investigation shows that energy and cooperation agreements executed since 2005 helped presidential campaigns, such as Nicaragua’s, who paid back to Chávez, and then to Maduro, helping them to expand their influence.

As it happened to Ortega and FSLN, the late Hugo Chávez activated Petrocaribe agreement in El Salvador at the same meeting in Miraflores Palace with El Salvador Farabundo Martí Front for National Liberation (FMLN) mayors. That way, the party got support for its upward run crowned with Mauricio Funes victory in March 2009 presidential elections and in the following election of Salvador Sánchez Cerén, five years later. To the charges of influencing internal processes, Chávez always answered negatively and accused presidents in power, who criticized him, for refusing the Venezuelan aid.

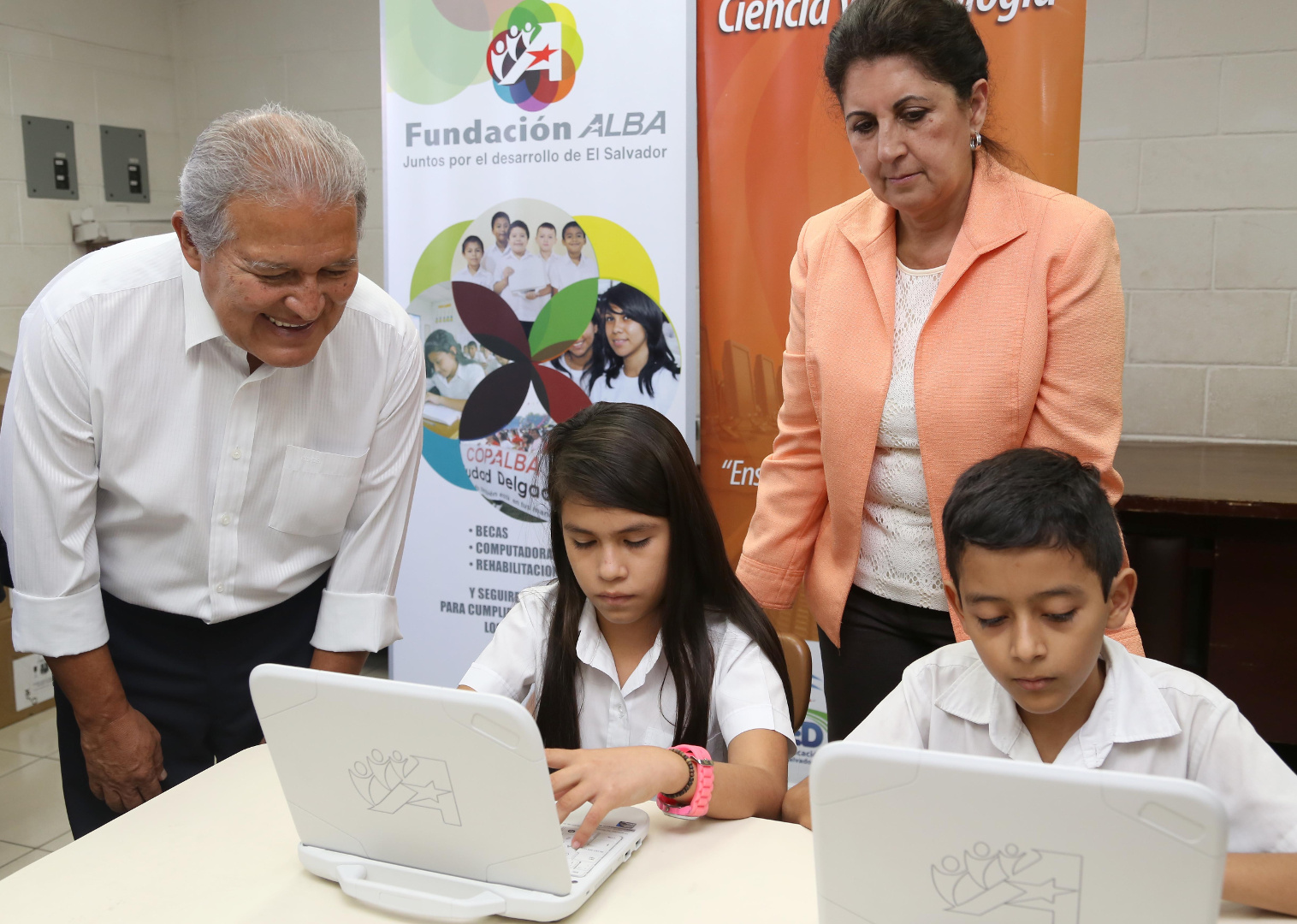

Salvador Sánchez Cerén as vice president of El Salvador and aspiring president gave computers to children with support given by the Alba Foundation/ LA PRENSA GRÁFICA, EL SALVADOR

The cooperation factor originated in Caracas for campaigns in the Caribbean, has also had a role. An example was Thimothy Harris, Prime Minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis, who promised a millionaire injection to the sugar producers’ protection fund and complied upon election in 2014 through a Venezuelan disbursement. Gaston Browne, Antigua and Barbuda Prime Minister, a day before ballots to be reelected in March 2018, announced that Venezuelan government had condoned half of Petrocaribe’s debt, which meant much more than a wink to electors about to be mobilized.

The opposite results were gained with the cuts if the aid, like it happened in Belize where Prime Minister Dean Barrow call early elections in 2015 before waiting for the preprogrammed date amid an adverse environment for his third reelection due to the reduction of oil aids that had kept him in power, according to local reports.

Great Chávez and Maduro allies, such as Prime Ministers Ralph Gonsalves, from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Rooselvelt Skerrit, from Dominica, have been able to evidence time and again their achievements developed with PDVSA support that have kept them in power for periods beyond ten years. Governments that had started before the creation of the energy aids but were supported in due time.

This #Petrofraude journalist investigation was able to discover at least 140 social programs in 12 countries benefited with the oil aids. Food, livestock, and stove distribution; free or preferentially-priced home gas distribution; elder and unemployed allowances; young entrepreneurs’ scholarships and microcredits; preferential sale of electrical energy and even payments for discretional use have been part of the list. Nothing was out of scope in the cooperation possibilities overseas that are nowadays lacking within Venezuela.

Many of the programs could be labeled as welfarism. In a PDVSA financial report submitted in 2010, a concerned the corporation had on the fact that not every program on the platform was aimed at “overcoming poverty” was stated. Petrocaribe’s official reports, on the other hand, have claimed sustainable and lasting social and economic achievements. Beyond that, aids expanded as a virus a dilemma the Venezuelan oil company had: Community wellbeing dependence on hydrocarbon market prices.

Selective Benefits

The end of the oil boom short-circuited Nicaragua with the aid accounts, but in the days when the Venezuelan mana was abundant, no one hid the search for Ortega’s political returns. The proselytizing tone, for instance, prevailed in a program event called 200,000 stoves and gas cylinders for the people held on October 25, 2008 in Managua’s Presidential House with the assistance of Ortega and Murillo, two weeks before city elections to strengthen the political foundations of the couple.

“We tell our president to trust us and that this 52% of the women we have will grow and will be evidenced on November 9 by voting square two!” stated Dalila Lanzas, who spoke on behalf of the beneficiaries of the initiative developed on account of Alba Caribe Fund, according to documents collected by #Petrofraude. The fund had been created under Petrocaribe umbrella to push social programs and had been activated with a seed capital of 50 million dollars contributed by Venezuela.

According to PDVSA documents collected by #Petrofraude, before 2010 four million dollars had been disbursed out of the 8.2 million budgeted. The results, however, were not up to the name of the program, because just 25,100 stoves and cylinders were handed out between 2007 and 2009 according to balances released by BCN, an institution pressed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to make more transparent the aid figures. The title of the effort was achieved barely over ten percent.

US$ 8.200.000

from the Fund Alba Caribbean were budgeted for the program " 200,000 stoves, 200,000 cylinders for the people"

Carolina Torras, Alba Caribe Fund Auditor, was in the stove program delivery, according to a transcription of the event. The PDVSA’s employee promised to assess the development of the program and communicate the results to the “relevant levels”, but there are no public records of her accounting reviews.

Resources channeled through Alba Caribe Fund were just a fraction of what has been executed in Nicaragua. Months after becoming president, Ortega signed a new agreement with Chávez that contemplated 25% of the oil invoice a non-reimbursable loan. The clause was a non-existent privilege under Petrocaribe’s model. Resources from this determination were to be used for social work that would get an unheard-of financial boost.

The diplomatic world registered the characteristics of the cooperation. “Venezuelan funds do not have set-forth conditions, allowing President Ortega to distribute them as he pleases. This makes them (…) more useful from a political point of view than traditional donors (…) that include conditions, supervision, and reviews”, was registered in an official cable of December 3, 2008 evidenced by Wikileaks.

“Venezuelan funds do not have set-forth conditions, allowing President Ortega to distribute them as he pleases. This makes them (…) more useful from a political point of view than traditional donors (…) that include conditions, supervision, and reviews”. ” — Official cable, December 2008, Wikileaks.

The Ortega-Chávez agreement set rules for the reimbursable components: 25% of the invoice could be paid within 25 years with 2% annual interests and the remaining 50% had to paid in cash within 90 days. The Sandinist president begged not to pay that short-term portion in cash but with food shipped by Alba de Nicaragua, the binational company created in 2006 and amended two years later to substitute municipalities as PDVSA’s partners for Nicaraguan Oil Company (PETRONIC).

Beyond Priorities

Nicaraguan authorities did not set education or healthcare, two key areas for international aid programs, as priority sectors to have resource allocation from this one-of-a-kind Venezuelan loan cooperation. This was the conclusion of a foreign cooperation report published by BCN reviewed by #Petrofraude.

Disaggregated data became available just in 2010. A total of 1.102 billion dollars were aimed at social programs and another 1.784 billion to socially productive projects between that year and 2017. Under education and sanitary care, including water, 73.6 million dollars, or less than 1% of the corresponding period total, were invested.

The rest of the programs have had a diverse scope of purposes, but the most known ones were destined to food distribution, electrical energy and transportation allowances, low-income alder and worker monthly complements, and to the construction of streets and housing projects.

The focus on the patronage distribution of some of these initiatives is evidenced by the Solidary Bond, labeled as a socially productive project that delivered 23 Dollars to 160,000 low-income workers of the public sector and 32 Dollars to 4,000 elders. In four years, 223 million Dollars were distributed. Since 2014, the Bond became financed by the national budget with a consequent reduction of beneficiaries.

Something similar happened to other allowances, such as Managua’s electrical and transportation fees. Alba del Carmen Castillo, 78, lives in Sábana Grande County in the Nicaraguan capital. She now needs 4.5 Dollars a month additionally to pay her electrical energy utility bill that had been subsidized since 2008 for 94% of the households countrywide. Ortega announced early this year that such aid shall gradually disappear between now and 2022.

Upon becoming president, the FSLN leader found a country with frequent blackouts. Chávez activated a fast emergency plant support operation that had very high operation costs to be fully paid by consumers. The Nicaraguan president, with the aid, was able to reverse the supply hardships as he had promised in campaign. The equipment sent by Venezuela became assets for the creation of Alba Generación, that became the main electricity source in the country. Although the government was able to improve the continuity of the service and the electricity contribution based on renewable sources, it has not been able to break fossil fuel dependence that currently represent 64% of the supply.

Fuel allowance for public transport also started to be gradually eliminated since 2015. The plan that had been current since 2008 covering taxis and busses whose drivers had e-cards to control the gallons of fuel with discount through the official contribution program. Just during the first year of the subsidy application, 50 million Dollars were used up.

Under this aid elimination context, Ortega has been facing protests since April 2018 with at least 325 casualties through October, according to Human Rights Interamerican Commission. Protests started due to a social security reform that charged employees and companies with higher contributions. The initial repression turned things worse. Many deaths have been attributed to law enforcement authorities and paramilitary groups linked to Ortega, which he has denied. Caracas diplomatic support has passed judgement on the situation and Maduro’s speeches, as well as public servants like Arreaza, have stated they have not seen human rights violations by the government, or unrest, but a conspiracy to overthrow the sandinist.

While reciprocal solidarity takes up entire speeches, money keeps flowing. Between 2015 and 2018, PDVSA loans have exceeded 470 million dollars. In those years, the deterioration of Venezuela’s financial situation has been striking. Enough would be to remind the period annual inflation: 180% in 2015, 275% in 2016, 2,600% in 2017, and 1,000,000% in 2018 (e), according to IMF estimates.

Achievements in Perspective

Chávez, at Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela, summit, were Petrocaribe was created, ratified the vision he had on the energy agreement. In his words, social projects within the framework would “empower with rights” the communities of benefited countries, help “overcome poverty”, and enable “healthcare, education availability and accessibility as well as cooperative and SME microfinancing”, among other objectives.

Five years later, the performance memories of PDV Caribe, PDV’s subsidiary created to manage energy agreements in Caribbean and Central American countries, stated that, among its greatest obstacles, there were facts that contradicted the official speech and the principles that encouraged the energy platform social strategy.

“Social and initiative efforts launched by the governments of some of the countries ascribed to Petrocaribe agreement are not aimed at overcoming poverty in a sustainable way” pointed out the report of the company in 2010 and that there were no legally binding standards in the agreement to avoid these practices. “these proposals have not been formulated mostly with a socially productive development vision but, rather, they tend to support traditional aid policies”, was added.

The document mentioned some countries lack of commitment” to contribute information” to follow up social projects financed through Alba Caribe Fund and through resources generated by long-term loans of the oil invoice. The latter are automatically managed by each beneficiary country and represent the main the main source of cash to finance projects.

In addition to these two channels, the agreement has other social investment mechanisms, Alba Alimentos Fund, aimed at food safety projects, and Bilateral Funds drafted additionally between Venezuela and some members of the alliance. One last source comes from the management performed directly through binational companies equivalent to Alba de Nicaragua that were created in association with PDV Caribe with state institutions in 12 countries. In brief, everything is part of a non-transparent complex money flow system.

A lead on how much was accomplished in the application of corrections was stated in the 2015 report by PDVSA Mercantile Commissioner, and officer in charge of controlling the adequate compliance of the corporation strategy. The text pointed out an evaluation of the energy agreements was in progress, including: “Verifying performed and to be performed social projects in allied countries with the financing of Alba Caribe Fund”. Nothing was mentioned about projects related to long-term financing or to those linked to the remaining financing mechanisms. There were no details on the first assessment results.

Observations submitted in the foregoing documents contrast with the content of the scarce Petrocaribe performance reports publicly disclosed. In 2015, it corresponded to the tenth anniversary of the platform listing a set of successes, being the first one the achievement of an energy safety scheme to the beneficiaries, which was especially important in times when high oil prices put pressure on importing economies.

“The energy leverage provided by Petrocaribe agreement has greatly contributed to social, economic, and cultural right progress” points out the chapter related to the alliance social and economic achievements. Support to 488 projects, including social programs and infrastructure projects, not individually specified. Most of them, 128, were related to housing and road sectors, according to it. The text emphasizes the importance of projects and allowances related to food and agriculture and to the access to utilities like electricity, domestic gas, fuel, and water which have protected vulnerable sector of the population. Although natural disasters are not specifically mentioned, it is a region exposed to hurricanes, and it has been one of the axles of the work.

The report points out that Petrocaribe membership and the Venezuelan cooperation umbrella enabled beneficiaries to weather the storm during the 2008 financial crisis that had a worldwide impact. The political selectivity focus and the lack of clear accounts leaves room for doubt on the effectiveness of the purposes announced for the agreement.

A Continental Campaign

“It is time to build our homeland. That is what we are doing with this first step”, said José Luis Merino in October 2013 announcing the creation of Alba Foundation that seemed like a mea culpa. Merino, one of the top FMLN leaders, the Salvadorean government party since 2009, celebrated the creation of the foundation six and a half years after Alba Petróleos de El Salvador (ALBAPES) had started selling fuel financed by Venezuela.

José Luis Merino, leader of the FMLN and senior adviser of Albapes, said in October 2013 that the time had come to "build homeland" when the Alba Foundation was established/ LA PRENSA GRÁFICA, EL SALVADOR

The company had been created, according to what had been explained, just with the objective to “build our homeland”, but there was little evidence of social program financing. Contributions had been dispersed under the traditional model: Sports tournament sponsorship, school makeover, college scholarships, and loans to linked companies.

All those supports lacked links to special government public policy or program had had no clear beneficiary selection criteria. “Programs assumed today by the Foundation, are programs that had started Alba Petróleos and, in an effort to organize them, focus them, and make them more efficient, Alba Foundation is now being created", explained the media.

ALBAPES was born because of the partnership between PDV Caribe, 60% ownership, and an FMLN municipality association named ENEPASA, with the remaining 40% ownership.

Chávez’s administration did not want to activate Petrocaribe in El Salvador through the dialogue of the national government that in 2006 was not under FMLN, a related party. The former guerrilla, that in 1992 laid down their rifles, to join the democratic political life, had achieved important progress in local governments and in the National Council, but had been defeated in the fight for the presidency in 1994, 1999, and 2004. After ALBAPES creation, three years went by and in 2009 FMLN broke the streak of presidential defeats.

The launching of Alba Foundation, that Wednesday October 30, 2013, took place on a decorated stage simulating a classroom. Among those presiding it, besides Merino, was the Vice-President of the Republic, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, a former guerrilla leader who had been appointed in 2009, next to president Mauricio Funes, a very popular journalist alien to FMLN past of guerrilla and revolution.

Sánchez Cerén, on this occasion, was wearing a different t-shirt: The presidential candidate one. Posters with his frozen smile and the “move on” slogan invaded the streets as part of his campaign for February 2, 2014 elections.

There were boys and girls on stage sitting at school desks with a white computer. Some were curious and overwhelmed checking the machine while other were performing as actors and actresses, smiling at the cameras, touching the equipment that had Alba Foundation stickers on the front. These computers illustrated what Merino was going to announce: The Foundation was going to deliver 4,000 of those computers to the Ministry of Education.

The school year was agonizing, and it would end on November 12, just as the presidential race was coming to its final stage. Alba Foundation managed to make three similar events before the closing of the educational cycle where Sánchez Cerén also participated. These acts helped Sánchez Cerén to hold high one of his most attractive proselytist flags: The promise that in his administration he would implement a program called: “A Child, a Computer”.

In April 2015, when he was already president, the program was officially launched using a more inclusive language: “A Boy, a Girl, a Computer”. The president made an announcement of an objective for yearend: Delivering 5,000 machines. Merino accompanied for many Saturdays to come Mer. President to the “Living Well” festival, to deliver computers and other Alba Foundation donations, such as musical instruments to schools and motorcycles to police officers.

In El Salvador, 54,000 computers were given to students between 2015 and 2018. Originally, the government created the expectation that they would give a computer to every girl and boy in the Central American country, a goal that was never met / PRESIDENCIA DE EL SALVADOR

The objective was not complied with by yearend, but three years later as acknowledged by the president in his presidential report of June 2018, when he stated that 54,000 machines had been delivered under a budget of 28.2 million dollars at half of the school institutions countrywide. From the total amount, ALBAPES contributed approximately 4.3 million dollars that represented just 15% of the investment. The rest was contributed by countries like Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, as well as other organizations and private companies.

The 54,000 delivered machines proved wrong the name of the program “A Boy, a Girl, a Computer” in a country where just public education has 800,000 students. The Ministry of Education has admitted the label was inaccurate, because the machines were to be shared in school and there would not be one for every student.

The computer plan has been the only contribution of ALBAPES dividends incorporated into a governmental public policy in El Salvador, according to the assessment conducted by #Petrofraude. The review of the company’s accounting shows that social contributions have been lower than the money sent to tax heavens.

The amounts managed by the company have been millionaire, as admitted by Merino. "Some people have become nervous because Alba Petróleos started operating just six or seven years ago with a million dollars and they say today it is worth over 400 million”, stated Merino. “We would like to correct them: It is 800 million that are going to change Salvadorians lives”, he added in the Foundation launching ceremony.

“Some people have become nervous because Alba Petróleos started operating just six or seven years ago with a million dollars and they say today it is worth over 400 million. We would like to correct them: It is 800 million that are going to change Salvadorians lives” —José Luis Merin

Although Alba Petróleos has refused to disclose its finances to the community or even to institutions like El Salvador Legislative Council, some facts have been questioned by the Audit Court of the Central American country. The institution determined seven years had gone by without ENEPASA’S mayors’ offices received interests in the capacity of ALBAPES partners and investors, despite having submitted profit reports. Salvadorian media publications like El Faro, El Mundo, and La Prensa Gráfica have documented that, on the contrary, they gambled on investing in failed projects of dozens of related companies.

Resources have also been destined, for instance, to the payment of labor liabilities of district employees. That happened to Francisco Castaneda, current Education Vice-Ministry who in 2012 used to be ALBAPES board of directors’ vice-president as Mayor of San Sebastián Salitrillo. On that year he managed a half-a-million-dollar loan from the binational company to pay a debt to toe employees’ pension fund and social security company. At that moment, ALBAPES was led by Asdrúbal Chávez, a cousin of the late Venezuelan president. Today, the company has claimed to the district the reimbursement of the money with interests; it is now led by Arena’s Mayor, a rival of FMLN.

A Strong Tissue

Beyond Central America, oil financing has also been instrumentalized for political purposes. The money has accompanied the performance of parties and presidents that have had long periods in power. Among them, two were consolidated as the main Chávez and Maduro’s allies: Roosevelt Skerrit and Ralph Gonsalves, who have been Prime Ministers of Dominica and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines since 2005 and 2001, respectively.

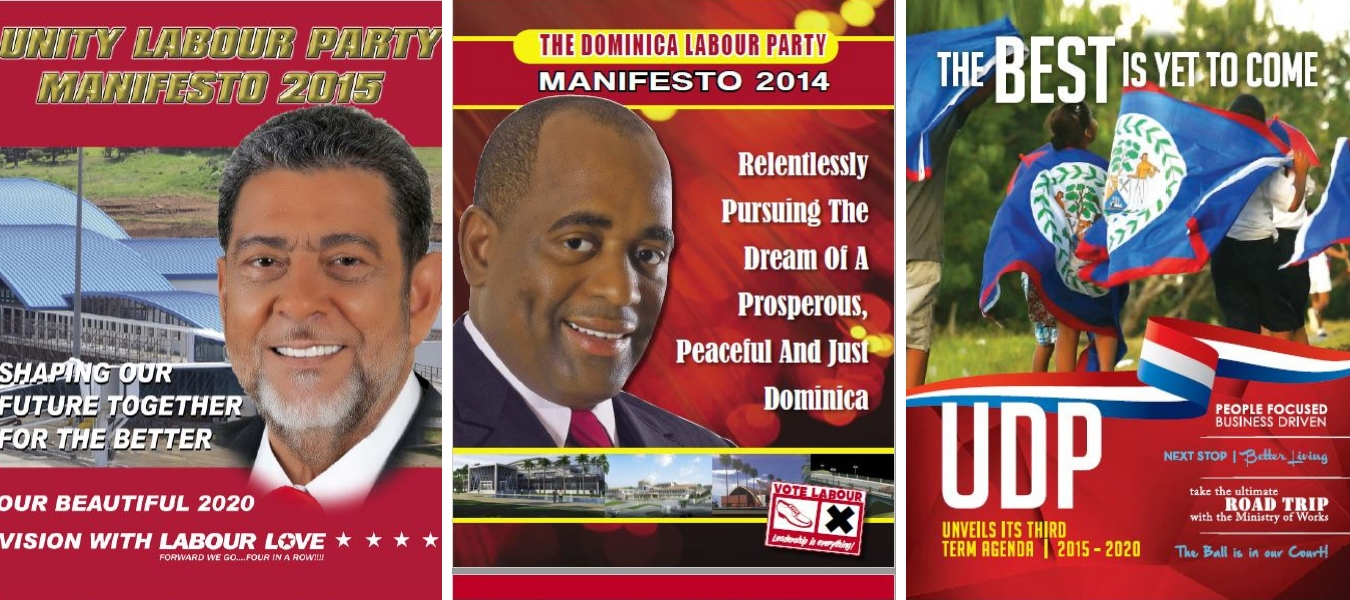

Skerrit’s Dominica Labor Party published a governmental plan booklet for the 2014 elections listing the projects achieved by Petrocaribe and ALBA cooperation, promising continuity. In the section dealing with Foreign Affairs, there was a key paragraph: “Benefits associated to those agreements included access to low-priced oil products, to 11 million dollars to finance the Housing Revolution, to donations for the recovery of hurricane damage for the Safety National Plan, for the construction of maritime defenses, for agricultural diversification, for tourist infrastructure, for scholarships, and for Melville airport renovation”. The quick list was a pearl to attract votes.

“The benefits that flowed from these agreements included access to low-price petroleum products; US$11 million to finance the Housing Revolution; grants for Hurricane Recovery, the National Security Programme, the construction of Sea Defense walls, Agricultural Diversification, Tourism Infrastructure, Scholarships and the Melville hall Airport upgrade”, —Robert Skerrit, 2014.

Gonsalves’ party published a similar document in the context of the general 2015 elections offering voters to keep their commitment to Alba and Petrocaribe, because, among the benefits received, they had had access to domestic gas and fuel at favorable conditions. The list, certainly, did not go into detail in terms of financed programs and infrastructure, highlighting the construction of Argyle Airport, a project with multinational funds but high Venezuelan share.

Dean Barrow’s United Democratic Party, Belize Prime Minister, published for 2015 general elections a document with his offer mentioning the beginning of a summer sports practice program financed by Petrocaribe. Barrow has held the position since 2008 and the Venezuelan oil agreement funds have been useful for the development of an infrastructure national plan whose audit has been claimed by the opposition.

Prime Ministers Ralph Gonsalves (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), Roosevelt Skerrit (Dominica) and Dean Barrow (Belize) made promises to their voters to get reelected under Venezuela's oil aid

Prime Ministers Ralph Gonsalves (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), Roosevelt Skerrit (Dominica) and Dean Barrow (Belize) made promises to their voters to get reelected under Venezuela's oil aid

Elections programmed for three years ago were called for earlier, according to local observers, due to the possibility that Barrow’s party would lose in the current scenario of low Venezuelan cooperation contributions due to dropping oil prices and PDVSA production setback. In the introduction speech for 2015 budget, the Prime Minister spoke about the issue and said that while Petrocaribe was in existence, the mechanism would be “fully used to our advantage; nevertheless, it is inherent to our focus to acknowledge and be ready for a moment when we swiftly would have to go back to regular ways of planning and spending”.

The Venezuelan financing bet for local allies also had Thimothy Harris, Saint Kitts and Nevis Prime Minister to promise in campaign the payment of about five million dollars to a former sugar workers’ protection fund.

Thimothy Harris, prime minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis, offered during his campaign to pay a millionaire amount to compensate the dismissed sugar workers. He did it with Venezuelan resources/ SAINT KITT AND NEVIS PHOTO STREAM

Local industry had closed in 2005 and, according to Harris in his public speeches, those who had worked for it had not been properly compensated. Thus, Team Unity party proposed creating a fixing mechanism. About 2,300 people would benefit, although one of the main issues to be solved was the large number of claims submitted by deceased former workers.

For December 2015, over a thousand applications had been received. Harris, on behalf of the government, thanked Saint Kitts and Nevis PDV, a company controlled by PDVSA in charge of Petrocaribe’s performance in that country. He did not forget something essential: “Our Cabinet records our enduring gratitude to President Nicolas Maduro and the Government and the People of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela”.

“Our Cabinet records our enduring gratitude to President Nicolas Maduro and the Government and the People of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela”, —Thimothy Harris, prime minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis.

Similar thanks were given by Gaston Browne, Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, when he announced hours before general elections where he was running for his first reelection, that he had finally paid an IMF loan and that the Venezuelan government had decided to condone 50% of the debt acquired by the country through the oil agreement. Not a despicable piece of information for electoral propaganda.

Funds coming from Petrocaribe and oil agreements represented a formidable platform for social aid and fueled Central American and Caribbean politics and rulers who were benefited by the millionaire cooperation to stay in power. After the Venezuelan oil boom was over, there are doubts on the sustainability of the achievements to fight poverty.