02.The deviation

of petrodollars

Under the energy agreement promoted by Venezuela, allied governments of this country had carte blanche to discretionally and without major controls manage the funds obtained thanks to oil loans. Part of the money was used for private investments, failed projects, the money was trapped in a tangle of companies linked with the region's rulers. Some of the characters involved are in the spotlight of investigations for money laundering.

The repeated cases of the increase in the value and real estate transactions of a land of 6,000 square meters, located on the Soyapango Army Boulevard, in San Salvador, illustrates how several governors and political leaders found their pot of fortune in Petrocaribe's resources. In just three months the price of this land went up to the skies and far beyond. It was originally valued at US $ 85,000, and after a short chain of purchases and sales, it was acquired for US $ 1,300,000 by the Dealer of Fuels and Lubricants, Sociedad Distribuidora de Combustibles y Lubricantes (Sodico), a company controlled by relatives of José Luis Merino, leader of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) that has governed El Salvador for nine years.

Sodico acquired the land in 2011 with one of the loans given by Alba Petróleos de El Salvador (Albapes), a company that has managed more than 1,100 million dollars in oil credits provided by the Venezuelan government through Petrocaribe in the Central American country. This is the star energy cooperation agreement created by the late Hugo Chávez in 2006, through which oil sales are financed on advantageous terms as a way to enhance the social management of the beneficiaries, most of whom are leaders of parties, such as the FMLN, aligned with the denominated Bolivarian revolution.

Merino holds the position of senior adviser in Albapes, but he is considered the power behind the throne in the company and in charge of financial relations with Venezuela. He is a figure that is under the scrutiny of the United States for alleged money laundering operations in different areas, including real estate. Three USA institutions are inquiring about his activities: The Department of Treasury, the DEA (anti-drug agency) and the FBI (federal investigation police).

.jpg)

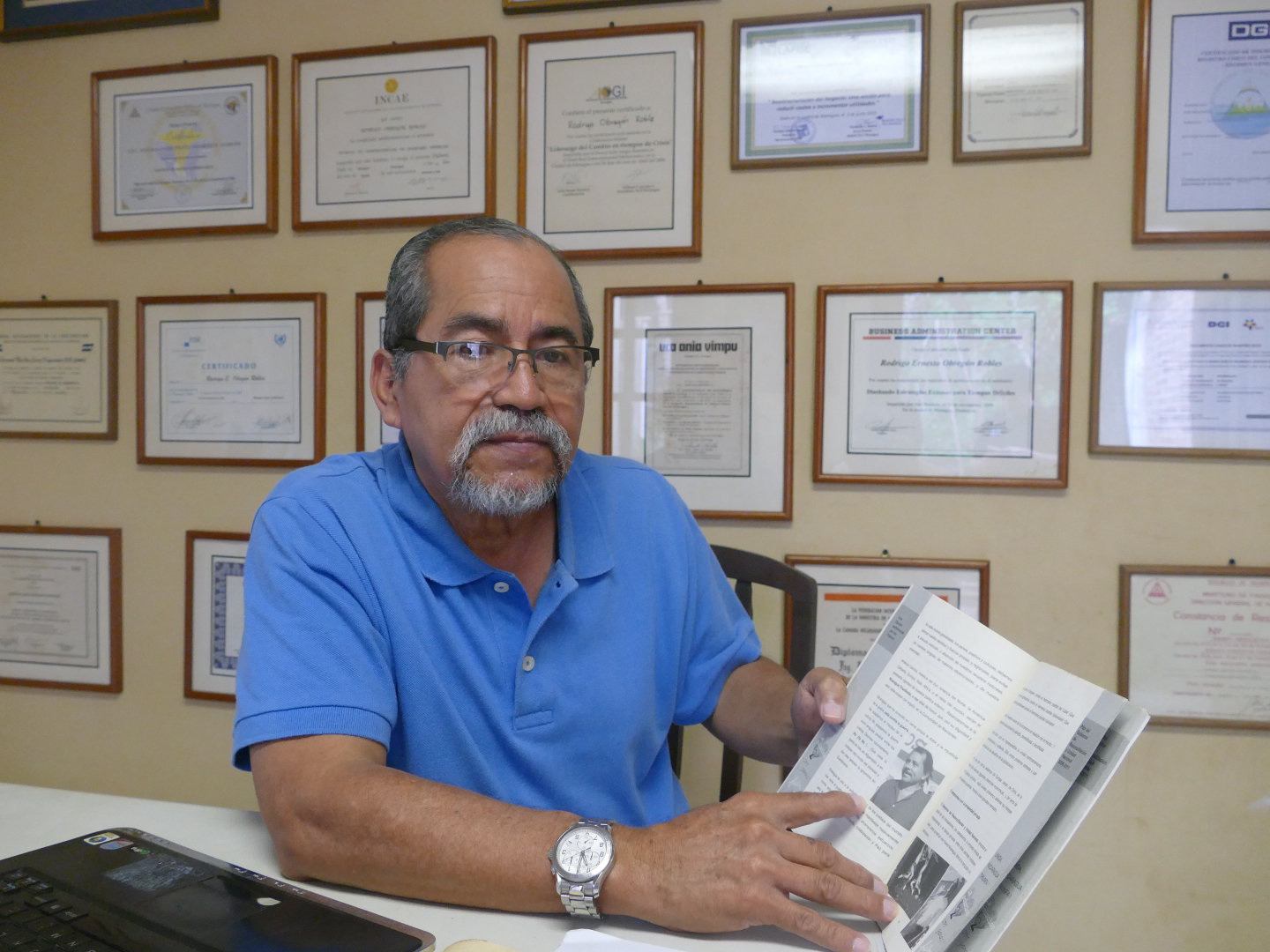

José Luis Merino, senior advisor to Alba Petróleos de El Salvador (Albapes), is investigated in the United States for alleged money laundering / LA PRENSA GRÁFICA, EL SALVADOR

The case of the land acquired by Sodico is very similar to the case of 107 properties whose records are in the Register of Property, Real Estate and Mortgages of the Central American country. This journalistic investigation of #Petrofraude, based on the review of hundreds of documents, reveals the existence of a speculative real estate scheme with losses for the company that has handled Venezuelan cooperation and benefits for individuals and legal entities, such as this one with connections with Merino, to whom the credits were granted. One example is Sodico, which received three mortgage loans for six million dollars from Albapes.

The tracking of the operations, before, during and after the arrival of the properties to the orbit of Albapes, allowed to identify abrupt changes in the purchase and sale prices; overvaluations of real estate offered as collateral for loans and the attribution of values that are underestimated or overestimated to the assets that are seized or delivered in payment due to the breach of commitments related to the financing. In some cases, even the company itself bought properties at prices above the market.

Albapes was founded in 2006 as a result of a partnership between Enepasa, a company that brought together 30 FMLN mayors, and PDV Caribe, a subsidiary of the state-run oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), responsible for oil credits in the region. The main function of the joint venture is the sale and distribution of oil derivatives obtained through the energy agreement. In theory, from its operations, resources must be generated to shore up social programs for Salvadorans.

In practice, as its balance sheets show, Albapes operates mainly as a financier who has spared no effort in offering loans, and in some cases with mortgage guarantees, for the amount of 500 million dollars given to at least 90 natural individuals and companies that were handpicked. The beneficiaries are mainly related to the fuel and energy business, but also with other economic purposes. The losses have been the common pattern in a management that seems not to seek profit but quite the opposite.

Albapes has made loans for more than 500 million dollars, according to their balance sheets/MELVIN RIVAS, LA PRENSA GRÁFICA EL SALVADOR

This investigation of #Petrofraude not only identified real estate operations whose amounts were raised or reduced without apparent explanations, but a characteristic pattern in the shareholding structure of companies that have been benefited with millionaire loans received from Albapes.

Many of them belong to other companies whose ownership in turn belongs to third-party companies, some of which are off shore and are registered in Panama or Curaçao. Among them, money was lent and the share composition of each one seems designed as a spider's web to mislead anyone who intends to follow the path of funds, which ultimately leads to figures from the Merino environment, as was established.

The destination of the Albapes loans is just an evidence of the labyrinthine financial scheme that was implemented in El Salvador with the resources originated in Venezuela. It is also an example of the advantageous situation seen in some countries of the continent, in relation with the management of cooperation agreements promoted by Chávez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro.

The oil agreements, with Petrocaribe at the head, involved the injection of more than 28 billion dollars in hydrocarbons and derivatives in 14 countries without including Cuba. Approximately half of the resources were delivered with loans payable in a maximum of 25 years and rates of up to two percent per year. The cascade of money implied a challenge for the transparency of regional institutions that did not approve the challenge. The management of the funds, according to the evidence gathered for this work, was done in an opaque environment with respect to the controls applied inside and outside the platform designed for the money to flow, which facilitated the emergence of resource diversion schemes that benefited power figures.

Petrocaribe, for example, created an audit mechanism that had only monitored a minimum part of these resources, as stated in the resolutions of the organization. In relation to the reports carried out by that audit body, there is no information open to the public. According to documents examined by #Petrofraude, the national comptrollers of the beneficiary countries did not go any further and have hardly mentioned the issue in most cases. Nor has the Comptroller General of the Republic in Venezuela disclosed any audit that has specifically tracked the management of PDV Caribe within the framework of the agreements.

Rafael Ramírez, a former president of PDVSA and a former oil minister who was one of the main articulators of Chavez's petrodiplomacy in Central America and the Caribbean, told reporters of #Petrofraude that "Everything was audited". However, no active spokesperson of the company responded to inquiries requests submitted by different media for this investigation.

“Everything was audited” — Rafael Ramírez, former president of PDVSA

The files of greater public importance regarding the handling of Venezuelan cooperation have so far been promoted by the Haitian Senate and the anti-money laundering police of Guyana, which have claimed to have found evidence of alleged crimes. In nations such as Belize, opposition leaders have unsuccessfully demanded accounting audits and in other countries such as Nicaragua, audits have shown that there have been no irregularities despite the evidence that Venezuelan cooperation made ruling party figures more wealthy. In the Dominican Republic neither the Audit of Accounts nor the internal management bodies of the Ministry of Finance, the unit from which the Petrocaribe Office operated in that country, have audited the use of the resources of the oil program during the previous years.

In El Salvador, for example, the deliberate attempt to silence inconsistencies in audits conducted by the Audit Court of the Republic to Albapes, has been formally denounced, and its officers, including Merino, did not respond to the interview requests that were presented by journalists of this investigation. More shadows than lights have prevailed within the management of the cooperation.

Labyrinth of relationships

Since its foundation, Sodico has had among its shareholders Carmen Leonor Aguilar Hurtado, wife of Sigfredo Merino, brother of the consultant of Albapes, and José Mauricio Cortez Avelar, a Salvadoran lawyer whom the US authorities that are investigating the leader of the FMLN point out as their main names.

With the six million dollars received in mortgage loans, the company not only acquired the land of Soyapango but six other properties, whose prices were raised during the purchase and sale operations prior to the acquisition

The increase in the price of land purchased in Soyapango occurred after a series of transactions that would attract the attention of any auditor. First a pharmaceutical company sold it to a group of three natural individuals. The next day, those buyers negotiated with a company that belonged to the legal representative of the same pharmaceutical company that had sold at first. Four months later, that same lawyer transferred the property to Sodico, who built a gas station on the land and had the Albapes flag waving.

Between 2006 and 2018, just for mortgage loans, which have property as collateral, Albapes granted 46 million dollars. Of this total, 39 million dollars were allocated to finance operations with the 107 properties related to the scheme identified by #Petrofraude. To date, the binational company has recovered a little more than 13 million dollars through dations in payment or seizures.

In 2016, Sodico itself suffered the seizure of seven of its properties, included the one in Soyapango, because until then, not much had been done to reduce its debts, which made a new administration of Venezuelan officials in charge of Albapes impatient, which demanded speed in the recovery of the real estate portfolio, a matter that in the past had not worried them too much. The creditor, however, assessed the properties for less money than the price paid by Sodico, even though the company had made improvements and investments to activate the gas stations.

The case of Sodico did not prevent that during 2017 to have Albapes lending again 19.3 million dollars to them. Journalists of this investigation could not identify which was the guarantee offered for the disbursement.

In Soyapango, San Salvador, the company Sodico acquired a land of 6,000 meters to install a gas station. The property was later seized by Albapes / MELVIN RIVAS, LA PRENSA GRÁFICA EL SALVADOR

Once you are able to uncover this corporate ownership model, you will see that Sodico shares a trait with other companies that have received financing, mortgage loans and other loans by Albapes: the connection has always been Merino, who often appears at the end of the line. This resembles so much the famous matrioskas from Russia, hollow dolls that contain smaller ones within themselves.

In the investigation of #Petrofraude, they were able to identify six nodes of companies interconnected with some type of relationships and always having an off shore private company or related to Albapes present, and also the attorney Cortez Avelar with some kind of role. "I do not work for José Luis but for his brother", words of the attorney as a refusal to admit his connection with the leader of the FMLN. The digital newspaper El Faro had already documented the existence of companies registered abroad related to Albapes and being used to evade tax obligations. The companies mentioned at the time are at the heart of the network of the Salvadoran matrioskas.

One of the most representative groups is associated with the company Termopuerto, incorporated to generate electricity using fossil fuels and which received from Albapes a total of 70 million dollars in credits.

Termopuerto owns 80 percent of the shares of Renova Energy, another company run by a brother of Merino. The first company financed the second company with 25 thousand dollars, a low amount but still shows a common practice among the companies that receive money from Albapes: that at the same time they become lenders of their related companies.

Until February 2018, Termopuerto was owned by Panamanian Investment for International Development (IDI), founded in 2011 having Cortez Avelar as treasurer and attorney-in-fact. The company domiciled in Panama sold 99 percent of its shares to a former director of the power company who had also been a shareholder of Renova Energy. That natural person, Daniel Rodríguez, paid US$18 million to the IDI for the share package, an amount beyond the reach of someone who in its income statements had only reported earnings of up to US $125,000 per year. He was asked on the matter, and he refused to offer any comment.

Until 2018, Termopuerto was owned by a Panamanian company controlled by a lawyer close to José Luis Merino, senior adviser of Albapes / MELVIN RIVAS, LA PRENSA GRÁFICA EL SALVADOR

The evidence of irregularities related to the management of Albapes are not only related to the issue of loans. In February 2014, the Audit Court of the Republic proposed to have a special audit that would include the accounts of the companies corresponding to years 2012 and 2013. The #Petrofraude team reviewed the work papers related to the evaluation. The documents were able to show that the auditors had difficulties to have access to all the required information, because some key pieces were in Venezuela. At the end, the court agreed to audit only year 2012, as requested by the management of the company.

In the work papers, the Audit Court included the report of the internal auditor of Albapes, who detected that in 2012 there were inconsistencies between the ledgers of the company and the financial balance presented to the Commercial Registry. They had reported 20 million dollars less in the balance sheet related to cash, accounts receivable in the long term and accounts receivable from related parties. Regarding this, the auditor recommended making a rectification so as not to violate the law.

In the work papers, the Audit Court included the report of the internal auditor of Albapes, who detected that in 2012 there were inconsistencies between the ledgers of the company and the financial balance presented to the Commercial Registry.

Two years later the correction had not been made and the Auditors of the Audit Court did not give any notice in that regard and qualified this and other six findings as minor observations. For 2012, the chair of Albapes was Asdrúbal Chávez, cousin of the late Venezuelan president.

The results of the report were kept secret and it was only in October of 2017 when they were known as a result of an external audit that the Legislative Assembly made to the Audit Court through an independent company. The auditors informed the deputies that the detected inconsistencies had indeed been declared as minor findings without clear justification. René Portillo Cuadra, an opposition member of the parliament, asked the Attorney General's Office to investigate why this had happened.

The deputy's complaint was shared with the media a month later, after another report was leaked to the press. This report was carried out by Fernández y Fernández, fiscal auditor of Albapes, who had concluded that the losses compromised the company's operations. None of this, however, has been a public issue for the authorities of Petrocaribe, a platform that for seven years financed Albapes without having El Salvador being formally adhered to the agreement, which was indeed carried out in 2014.

The investigations conducted in the United States with respect to Merino are related to the Salvadoran plot. US authorities attribute connections with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a guerrilla group that demobilized in 2018 and made its association with drug trafficking as one of its main activities. The subversive organization rendered accounts of its assets in the process of peace negotiation, but in Colombia it is believed that much more has been legitimized and remains hidden. The US Congress has paid attention to appearances in this regard, one of them is Douglas Farah, president of IBI Consultants, a company of strategic intelligence, which ensures that Albapes has been one of the facades for this.

"I am the auditor general"

"Good afternoon, Nicaraguan people. I do not know if everyone here knows me, but I am the general auditor of Petrocaribe". This phrase is recorded in a transcript of a public act held at the Presidential House in Managua, Nicaragua, on October 25, 2008, in which gas cylinders and cookers were given to citizens of that country and paid by the Venezuelan cooperation.

Daniel Ortega who had become President of Nicaragua as the candidate of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), was present and also his wife Rosario Murillo and the official who spoke these words, Carolina Torras, manager of Functional Audit of PDVSA, who by then, according to information obtained by #Petrofraude, was 27 years old and had been working in PDVSA during four years.

"I wanted to share, that in compliance with the Petrocaribe energy agreement, the Verification and Audit Mechanism was recently approved in July during the last summit. We are currently starting this audit to the project 200 thousand kitchens and 200 thousand cylinders and (...), we will be sharing with you each of the phases of the audit and we will communicate the outcomes to the corresponding levels. It is an honor for me to be here, thank you for the invitation, "she said, according to the text reproduced by the web site Nicaragua Triunfa. Ortega's response was that of a political veteran. "Long live the beautiful women of Nicaragua," he exclaimed and then went on to another topic without going back.

The "corresponding levels" mentioned by Torras kept the findings under lock and key. The auditor's mechanism approved at the summit of ministers of Maracaibo, Venezuela, had a limited scope and would be specific to the programs and works financed by the Alba Caribe Fund, which is only one source of the resources. The other channels are the Alba Alimentos Fund, bilateral funds established with some of the countries, the social contributions of the binational companies in which PDV Caribe is a member and the long-term loans that allow each country to have resources for programs that they can manage autonomously.

Through the Alba Caribe Fund, approximately 179 million dollars were channeled into 88 projects, according to documents obtained for this investigation. Only for the Nicaraguan kitchens, 8.2 million dollars were budgeted, of which half of them were disbursed during 2010.

US$ 179.000.000

were disbursed for projects through the Alba Caribe Fund. It has been a fraction of the disbursements of Petrocaribe

There were hardly any referential data on the audit mechanism in the ministerial resolutions of Petrocaribe. For example, in July 2009, at the meeting in Basseterre, Saint Kitts and Nevis, it was stated that it had helped to improve the performance of the alliance and in the 2012 meeting in Managua, an annual plan of accounting revisions was discussed. Despite the fact that the platform was promoted with public resources, a transparency formula was never established nor was mentioned in reports available to the citizens regarding any minimum failure to correct with the agreement. What has been known has been a mosaic of information based on internal leaks and some public pieces.

A clue was disclosed when Hernán Ferrer, commercial commissioner of PDVSA, revealed in his 2015 report that the corporation was carrying out a general evaluation of the energy agreements, which included the review of the social projects of the Alba Caribe Fund and the oil infrastructure works in which the corporation made investment. In the document of the following year, the last one available, it did not refer to the progress made in that evaluation process that was pending for a decade, but did point out that Petrocaribe was reviewed, among other regional agreements, to prevent the losses that had been generated .

US$ 3.762.700.000

were disbursed to Nicaragua in oil loans

Torras, no longer working in PDVSA since 2016, was tried to be contacted for this investigation without success. Today she runs a water filter company in Caracas and shows herself in her social networks as a proud traveler having visited 43 countries. Nicaragua has been one of the countries she has visited, and has been a country surrounded by controversy in connection with the benefits given by the Venezuelan cooperation.

Carolina Torras led the Petrocaribe Verification and Audit Mechanism. Today in her social networks she describes herself as a traveler. Here you can see her in Mali

Until the first semester of 2018, according to official data, the aid from the South American country had exceeded 3.760 million dollars in oil loans and 1,000 million in investments of Pdvsa for electric works and also for storage and refining of fuels associated with the facilities Gran Sueño de Bolivar. The depression of the oil market has lowered the rate of disbursements, which, however, have been more than 490 million dollars only in credits given for hydrocarbons and derivatives during the last three years, in which the crisis in Venezuela worsened and its consequences have an impact on the continent.

A privatized chaos that people will pay

The oil loans given to Nicaragua were presented from the beginning by the Ortega government and by the Central Bank of that country as a private contribution. That has been the original sin of a scheme for the management of Venezuelan cooperation that was as intricate as that of El Salvador and that was orchestrated with the complacency of Caracas. The Chairs of PDV Caribe and José Francisco López, have been involved in its management, this last one has been the right-hand man of Ortega and treasurer of the FSLN; he was sanctioned by the US Department of Treasury in July 2018, for his alleged links with operations related with corruption and with money laundering.

The management of the millionaire contributions fell unprecedentedly in an agricultural credit and savings cooperative called Caja Rural Nacional (Caruna) and in the binational company Alba de Nicaragua (Albanisa). The first one had a budget that could be managed outside the controls applied to public institutions and the second one, had as objective to receive and distribute fuels, but was transformed into an emporium of companies with dissimilar businesses that has been inscrutable.

The story of how it came to that point reflects the analysis of Chavez and Ortega to find the path with fewer obstacles. The first attempt occurred when the former FSLN commander was still a candidate during the elections of November 2006. The late president ordered PDV Caribe, a PDVSA subsidiary, to set up a company to execute the Petrocaribe agreement in partnership with the Association of Municipalities of Nicaragua, which was controlled by Sandinismo. Both founded Alba de Nicaragua, which was known with the acronym Albanic, through which fuel was dispatched, and at the end, mayors of the party of Ortega distributed it during the electoral campaign to cooperatives of transporters and agricultural producers.

When Ortega reached the presidency, the parties worked to purify the scheme. First, in January 2007, the Nicaraguan head of government signed the Petrocaribe Energy Cooperation Agreement to incorporate his country as a state in the platform. The text even received parliamentary ratification. Four months later, in April of that same year, there was a binational ratification. Ortega then signed the Energy Agreement of the Bolivarian Alliance of the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), which did not have legislative approval, but which Chávez applied with preference to his ally, which served as the basis for getting rid of vigilance, as documented by the Nicaraguan web site Confidencial, a partner in the investigation of #Petrofraude, and Nicaraguan economists such as Adolfo Acevedo.

The agreement established that its execution should be carried out through a binational company. That role was assumed by a new version of Alba of Nicaragua that started to be called Albanisa. The change was not only of the acronym. The association of municipalities was displaced as a member of PDV Caribe and its place was occupied by the state-owned Empresa Nicaragüense de Petróleo (Petronic), chaired by José Francisco López, who became vice-chair of the new organization. The governments, however, also agreed that Caruna would manage part of the funds. "The owner of the money, PDVSA, decides that this is the way it should be done, and it is stated in the contract," words of Lopez when he was asked during an interview with the local web site Tortilla con Sal.

Francisco López, treasurer of the FSLN, had key responsibilities in the handling of Venezuelan cooperation. He was sanctioned by the United States Department of the Treasury in 2018 / URIEL MOLINA, LA PRENSA NICARAGUA

The scheme distributed the components in an advantageous way for Ortega, better than that contemplated in the Petrocaribe model. Half of the oil bill had to be paid in a maximum of 90 days and the Sandinista government insisted on paying it with food and not with cash. A 25 percent was declared a non-refundable loan. Each dispatch would be charged as part of the oil bill, but the money would never go to the Venezuelan treasury but to a fund for social policy that was called Alba. Another 25 percent would be transformed into loans payable with a maximum of 25 years and with the collection of up to two percent of interest rate. The budget would also be available in the present and Caruna would manage it. He then acquired a flow which was used to finance social programs and public companies.

Concerns about Caruna's performance were seen in PDVSA internal documents. In a draft contract disclosed in 2014 by Confidencial, showed that lawyers from the Venezuelan oil corporation pointed out that previous agreements signed with the cooperative contained clauses that could "cause confusion with respect to their proper compliance" and therefore should be replaced. The lawyers considered that normalizing the relationship with the cooperative was an obligation they had with the assets of Venezuelans. The pressure caused to have Caruna outcasted in 2016, and to have the financial management of the agreement managed by the Corporate Bank (Bancorp), a subsidiary of Albanisa, which had López among its directors.

With the funds managed by Caruna and then by the bank, millionaire financings were made to the public sector. For example, an updated review carried out by this investigation #Petrofraude, identified at least 24 loans of 466 million dollars applied to the state water, energy, aeronautics and postal companies, which the government of Nicaragua has assumed as obligations to be paid. Only the Nicaraguan Electricity Company (ENEL) accrued debts of more than 123 million dollars that were allocated, according to an independent audit, to operating expenses and maintenance projects and improvements to power generating plants.

The PDVSA lawyers who drafted a new contract to solve the gaps in the relationship with Caruna, also made comments about Albanisa, which they described as a "bureaucratic mega-monster" amid complaints about the "misleading interpretation" of the bilateral cooperation agreement that had led the relationship to a lack of control.

Former members of the PDVSA auditing team, consulted for this work, confirmed that the Nicaragua case was especially sensitive within the corporation. The authorities of that country had high-level support within the company or even in the Foreign Ministry, which was occupied by Maduro, when concerns arose regarding the handling of money. "We were pressured if we expressed doubts." In 2009, Confidencial revealed interviews with internal sources of PDVSA who stated that the lack of internal controls in Albanisa and the discretionality of López motivated the sending of a delegation that included a team of auditors including Torras and the director of Finances, Víctor Aular. Those consulted by the Nicaraguan media said that many strategies were used to hide the information, and to prevent these group of auditors from working and they were even threatened of not letting them enter if they presented the visit as an audit and not as a support activity.

The frictions caused the Comptroller General of Nicaragua to intervene and to examine the accounts of Albanisa from its foundation until 2011. The examination concluded that during the period the company "complied with all important aspects" with the applicable legislation. This report was published in 2015, long after the crisis generated by Paniagua.

Despite these results, a former official such as Rodrigo Obregón, who was deputy manager of the binational company, has publicly denounced that the management of the company does not follow reasonable logic, which makes him think that money laundering should be investigated.

The acquisition of assets not related to the central mission of the company, the constant formulation of failed projects, the creation of companies with different objectives and the millionaire investment in unfinished works such as the refinery Gran Sueño de Bolívar are part of the list of elements that do not make sense for Obregón. "I did not have access to the audit report of the comptroller's office. They told me to sign in blank and I said no. Albanisa can not be audited, "he said during an interview with journalists from #Petrofraude. "We must understand that the governments of Venezuela and Nicaragua are mafias that have strengthened their collaboration with each other."

Rodrigo Obregón, former vice-manager of Albanisa, states that the binational state company is non auditable/ JULIO LÓPEZ

The authorities of the United States are convinced that this has been the case and that is why they have applied sanctions against López, under the terms of the Magnistky law, which allows the US government to impose economic punishments, such as the freezing of assets and prohibitions of transactions in the financial system, to foreign citizens that the US government considers involved in acts of corruption or violations of human rights.

López was credited with having given enormous amounts of public treasury money to Nicaraguan leaders, diverting money from infrastructure works and having a network of officials involved with corruption. The sanction was imposed in the context of the anti-government protests that left more than 325 dead as of October according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and accusations against Ortega for human rights violations. Along with the Salvadoran José Luis Merino, López is part of the key group of leaders who managed Venezuelan resources in the continent.

Leads in the Caribbean

The national comptroller authorities of other countries involved in the energy agreements do not seem to have gone much further than those of Nicaragua and El Salvador. The investigation of #Petrofraude reviewed 47 annual or special reports published in the platforms of the comptroller's offices or accounts of 12 Caribbean countries that disclose them online and only found references to relevant failures in specific cases of Jamaica, Guyana and Haiti.

In Jamaica, loans for more than 100 million dollars were given to four institutions without compliance with protocols. In Guyana, differences between amounts received and figures transferred were questioned. In Haiti, irregularities were examined in the development of an infrastructure plan.

However, inquiries of greater public projection have been carried out by the Special Unit against Organized Crime (SOCU) of the Guyana Police Force and by the Haitian Senate, which carried out two audits. In both cases, they have followed the lead of alleged fraudulent handling. The Guyanese investigations have put their attention mainly to an entity that exported to Venezuela thanks to Petrocaribe. It has been the Board for the Development of Rice of Guyana, governmental institution the one responsible for the shipments in the commercial compensation scheme that allows to pay debts with essential goods.

After the end of the mandate of President Donald Ramotar of the People's Progressive Party, investigations began by the initiative of his replacement: David Granger, of the National People's Congress. Members of the new government accused their predecessors of having taken out 15 million dollars from a fund used to pay the exporters, which was denied by the defendants. An audit was then ordered to evaluate the board's accounts.

After a cabinet meeting in January 2017, Raphael Trotman, Minister of the Environment, said that they had found evidence of loans without endorsement or without approval of the entire board of directors and of foreign exchange speculation operations, as reported by the local media. According to the spokesperson, the institution managed an approximate of 500 million dollars of the Petrocaribe Fund during three years.

"It is a case in which there are more and more involved," confirms Sidney Jamen, head of SOCU, interviewed for this work in Georgetown. He is cautious to provide more information. The organization he heads held a visit to secure evidence at the board's headquarters and interrogated six of its former directors, including former general manager Dharamkumar Seeraj. All were finally accused in May 2017 for an alleged breach of the obligation to record money movements in the accounting books of the institution.

“It is a case in which there are more and more involved” — Sidney Jamen, head of the Special Unit against Organized Crime.

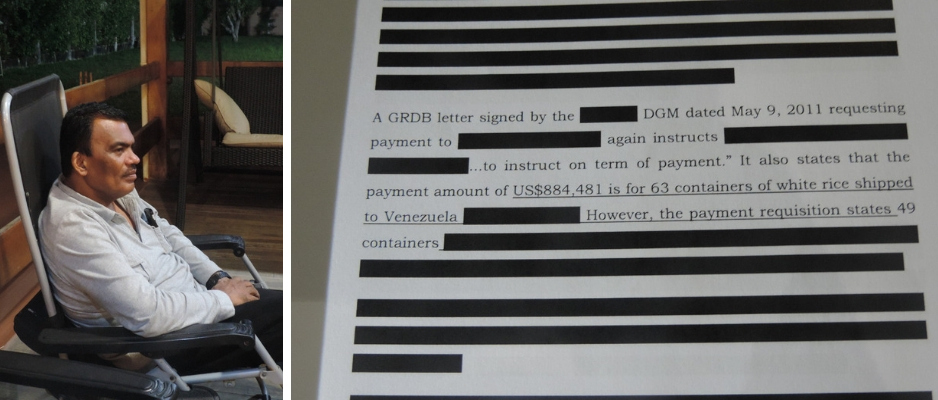

The defendant are parliamentary or compatible figures of the previous ruling party. Seeraj and Mandalall Ramja, who were indicted, told journalists of this investigation, that they are innocent of the charges and that the resources for which they were involved were not even connected to funds from the energy agreement with the Venezuelan government.

Anil Nandall, Ramja's defense attorney and former attorney general of Guyana, also said that his client has been denied the right to defense, because he has not been allowed to read the audit document that triggered the accusation. According to him, a copy with entire pages crossed out was provided to him last June. There are barely any readable fragments and in some of those passages operations that involved Venezuela are mentioned.

The authorities that now run the rice board declined to comment on how the development of operations with Venezuela was, despite the fact that interviews were requested in person and also in writing. Winston Jordan, Minister of Finance, who provided resources that were managed in the compensation, also did not accept to offer statements, beyond the ratification that in his opinion there was undue use of the funds associated with the agreement with Venezuela.

Anil Nandall, former Attorney General of Guyana, is the defense counsel for the Rice Development Board of that country investigated for alleged financial crimes / GRISHA VERA, EL PITAZO

The case of Haiti has been documented mainly by parliamentary initiative and as a response to the malaise that exists in that country, the poorest of the continent, with respect to the use of cooperation resources. One institution was the main target of the scrutiny of the audit promoted by the Senate: The Office of Monetization of Development Aid (BMPAD), which centralizes external cooperation in Haiti.

An independent company made the assessment and saw, among other findings, that the financial statements did not reflect the true situation of the Petrocaribe Fund, that the accounts in dollars were expressed at exchange rates that were not those of the Central Bank of Haiti, and also that the procedural manuals were not available for verification and debt write-off for more than 300 million dollars had not translated into an equivalent increase in availabilities due to a lack of regulations that anticipated this situation.

Senator Youri Latortue told reporters of this investigation, that the National Credit Bank of Haiti detected an account managed by Venezuelan officials that has been used to receive part of the long-term debt payments. The parliamentarian considered this action as something without explanation given the enormous economic difficulties of Venezuela facing the fall of oil prices. BMPAD's former director, Eustache Saint Lot, told the Senate Commission led by Latortue that he audited Petrocaribe's and the way that the Venezuelan authorities worked in order to not repatriate those funds to use them at their discretion in other projects in Haiti.

The biggest finding, however, was a pattern of contracting of infrastructure works that led to fraud in many of them and that were budgeted with resources for more than 2.1 billions dollars. As a result of the audit, criMinal public action was recommended against 14 people who held relevant positions not only within the BMPAD but outside the institution. Up till date, no judicial result has been materialized.

In other countries, claims for audits did not go beyond promises. The opposition in Belize has demanded the Supreme Audit Institution to examine Petrocaribe's accounts, at least twice during the past three years. In August 2017, Julius Spat, deputy of the United People's Party and chairman of the Public Accounts Committee of the National Assembly said "It's time to do it,". He said this during a televised statement in which he added that citizens had no idea how nor in what resources were spent. Two years before, Spat had asked for the same thing and all he got was an affirmative promise from the auditor Dorothy Bradley.

The execution of the agreement with Venezuela has fallen in the binational company Alba Petrocaribe Belize Energy Limited (Apbel), a partnership between PDV Caribe and Belize Petroleum and Energy Limited. The agreement has allowed the Central American country to receive financing for more than 200 million dollars, despite interruptions in supplies between 2009 and 2012 and at the beginning of last year. The resources have been used for purposes such as the development of a national infrastructure program, but also for other purposes such as the creation of a national bank and to compensate the owners of a telecommunications company nationalized in 2009.

The debate over the use of the funds acquired an unprecedented intensity in 2015 after Dean Barrow, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance since 2008, proposed the Parliament to have a special retroactive law for the approval of expenditures made by his government with contributions from Apbel. Local legislation requires that any loan granted by a financial institution above 10 million Belizean dollars must have prior parliamentary approval and therefore critics considered that the project violated the regulatory framework.

Dean Barrow has been Prime Minister of Belize for one decade. In 2015, he generated controversy in his country for proposing a law that retroactively authorized him to use Petrocaribe funds / FOREIGN AND COMMOWEALTH OFFICE

Trade unions and industrialists, teachers and even churches rejected the project at the time. This forced Barrow to propose amendments to offer greater guarantees of control that, however, did not change the substantive: the possibility of taking millionaire loans from the binational company without the obligation to receive a green light from the National Assembly.

The governor had argued since the previous year, that the characteristics of the energy agreement, which submits the availability of resources to oil prices, prevented him from presenting advance planning to the parliamentarians and that Apbel is not a financial institution in the sense that is defined by the law that requires legislative approval. Also, in his defense, he had said that the management has been transparent, that the works were open to the public and that the Venezuelan allies had audited the accounts

Barrow's proposal was finally approved by the Parliament and Spat decided to withdraw a judicial appeal filed with the Supreme Court that expected to block the prime minister's intention. However, two years later the deputy requested an audit of the accounts. Dorothy Bradley, auditor of the nation, did not respond to an interview request for this work, but a senior source of her office said that the audit could not be done due to lack of resources that have been requested, but have not been delivered by the Ministry of Finance, managed by Barrow. In Belize, as in other parts of the continent, the execution of audits on the use of Venezuelan cooperation continues to be a pending demand to be performed.