01.The business that emptied the pockets of Venezuelans

After a decade of Venezuela leading energy agreements with 14 countries delivering millions of barrels of oil, Venezuelans needs are growing. Payments, meant to be in kind, in many cases was translated into a fraudulent overpriced and fake delivery system to benefit regional political alliances and local corruption instead of Venezuelans.

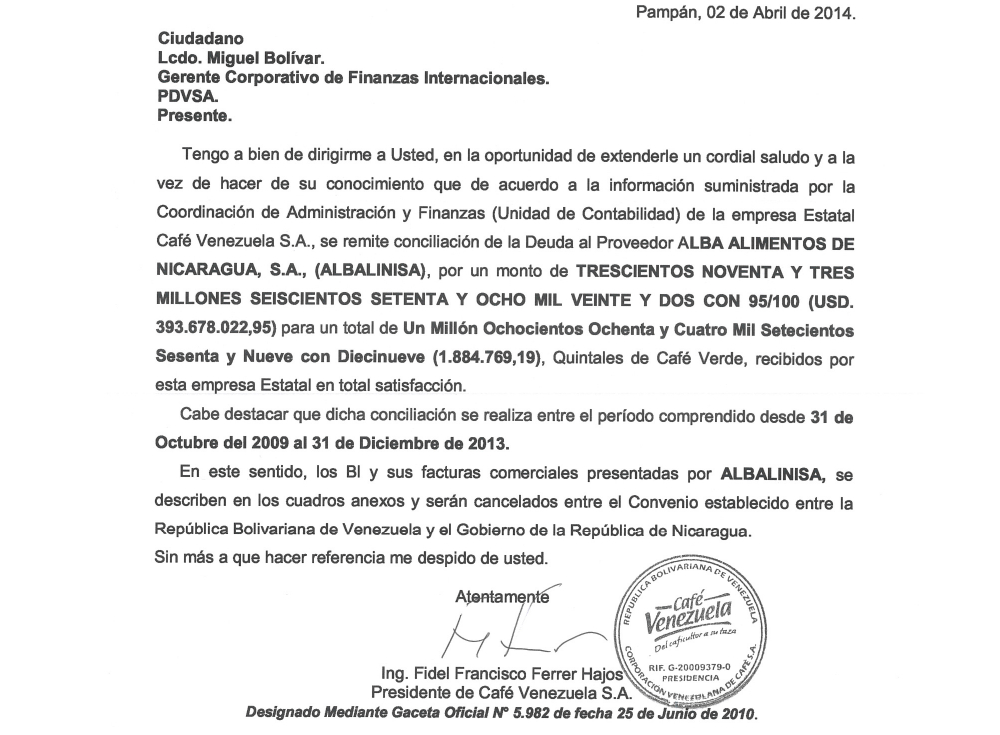

“It’s very urgent to seal the plan with Nicaragua”, wrote Nicolás Maduro, President of Venezuela, by his authorizing signature. The document, executed on March 23, 2015, detailed an import offer for 446.3 million dollars in coffee, beef, sugar, cattle, sunflower oil, milk, and black beans to be shipped that year from the Central American nation governed by Daniel Ortega, his ally.

More than 300 million dollars were focused in the first three lines, quoted at prices that exceeded international references or were among the highest prices presented in the recent history of Nicaraguan exports. This indulgence was assumed by the Venezuelan government, despite the fact that the global oil market on which its finances and those of the country rely upon, had already suffered a 50 percent collapse.

While Maduro blamed the economic war for the lack of assets and for the tsunami-like inflation, he authorized buying green coffee at 243 dollars a bushel and beef at 5,690 dollar a ton, both higher than the highest selling averages in 20 years, according to calculations based on Nicaragua’s Central Bank (BCN) data. Sugar was about 65% higher than New York quotation, considered benchmark. “It could be said than most goods were overpriced”, said a local expert agricultural economy and development professor who was asked to analyze the list of goods authorized by Maduro.

Documents show Nicolás Maduro's approval of a Nicaraguan food purchase operation with prices above market references

The plan authorized by Venezuelan President became reality under a contract charged to public resources executed by companies controlled by both countries. The business represented the corollary of a series of transactions from Nicaragua to Venezuela for about 2.7 billion dollars since 2008.

Negotiations took place through a debt compensation system for Central American and Caribbean nations to pay with goods part of the oil supplies granted by the Venezuelan government under the energy cooperation agreement conditions set forth by former President Hugo Chávez.

The range included Petrocaribe, the flag program, and other subscribed at the heart of Alianza Bolivariana de los Pueblos de Nuestra América (ALBA), the spine of Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), the state corporation network over which oil manna poured until July 2014 that today is cornered by debts, corruption scandals, money laundering, and production and refining capacity setback.

#Petrofraude journalist research has revealed that what happened with the budget authorized by Maduro in March 2015 was not an isolated case. These types of negotiations are an overprice pattern example pinpointed in a series of commercial compensation operations that involved, at least, Nicaragua, Guyana, Dominican Republic, and El Salvador, the most benefitted countries through the compensation system that Maduro currently proposes as the model for a regional commercial zone.

Based on the oil corporation internal documents and accountability, public information requests, foreign trade statistics, and interviews to sources linked to the transactions, #Petrofraude proved that Venezuelans’ millions of dollars have been drained in deals whose terms kept them from getting higher amounts of food.

The paradox is not only because the energy agreements were submitted as fair trade international benchmarks because oil was delivered with concessions, but for the current hardship Venezuelans have had to endure in the last four years with the highest levels of malnutrition in the continent, according to the United Nations, that closed 2018 with a 1,000,000% inflation, according to the International Monetary Fund projections.

Hyperinflation and shortage of food are affecting Venezuelan population / RAYNER PEÑA EL PITAZO, VENEZUELA

Collected evidence reflects inconsistencies between price and volume information in the official documents linked to the operations and on reports of bodies that process statistics related to the agreements or to customs activity. Such differences had uncertain destinations to finance corruption, according to the Venezuelan oil company sources.

The scenario, according to accessed documents, was favored by the lack of control at PDVSA’s instances that had direct responsibilities to overview the transactions. Part of these operations involved people and companies that were penalized, investigated, or surveilled by the Department of the Treasury of the United States for alleged money laundering.

This journalistic research also has revealed that businessmen linked to the so-called Bolivarian Revolution governments sealed profitable transactions amid the system without the least public scrutiny.

No PDVSA spokesperson answered our information requests for this project. Rafael Ramírez, former PDVSA CEO, former Energy Minister under the Chávez administration, and coordinator of the Venezuelan oil policies in the region, spoke about the subject but denied irregularities or lack of transparency during his tenure, 2004-2013.

“Everything is audited”, he said. “Our work was always overseen. If the General Comptroller of the Nation detected inconsistencies, he called us. If our auditors detected inconsistencies, I would not sign”.

The late President Hugo Chávez (center), his successor and former chancellor, Nicolás Maduro (left) and the former president of PDVSA, Rafael Ramírez (right), were the architects of the oil agreements that benefited countries of the Caribbean and Central America / EFRÉN HERNÁNDEZ, THE NATIONAL NEWSPAPER (CARACAS)

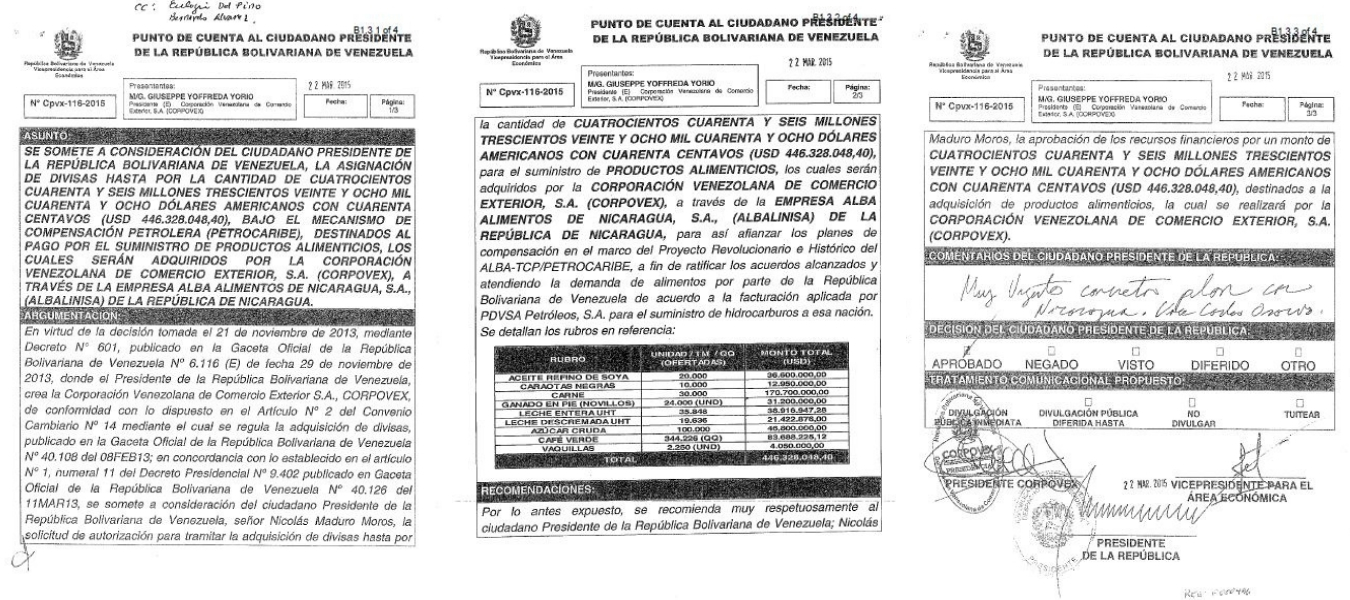

Nevertheless, an auditing report indicates that the commercial mechanism that has traded over 3.7 billion dollars has lacked since its foundation, over a decade ago, the right follow-up protocols.

The document, dated April 2017, collects reports auditors sent their superiors to be reviewed. It states that the International Finance Corporate Management, at the core of the scheme, never set out effective regulations to control processes: “The commercial compensation process review evidenced the absence of a standard adjusted to the tasks to be performed”.

Auditors imputed PDV Caribe, a PDVSA subsidiary founded in 2006 to oversee Petrocaribe and ALBA linked agreements, charges for not having acted as the compensation centralizing body: “It does not have enough support documentation on the items acquired by the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela”. Analysts were talking about invoices, lading bills, and quality reports, among others, that should have been filed and forwarded to financial management for the respective conciliation.

In 2017 a report was sent by the PDVSA auditors to the top managers of the company. Within the report they show the shortcomings of the compensation system that promoted the lack of control in the oil payment mechanism with goods.

The omission becomes relevant considering the subsidiary had a strategic international role and was managed since its foundation by people close to Chávez and Maduro, including the late Bernardo Álvarez, who was President of the Organization of American States Permanent Council, and Asdrúbal Chávez, President Chávez cousin, who became Oil Minister.

In practice, according to PDVSA sources, the Venezuelan food import public company network assumed the role to process the purchases and to control support documents. Among these companies, there were Agricultural Supply Corporation (CASA), Foreign Trade Corporation (Corpovex), and Venezuelan Food Corporation (CVAL), no longer operational.

The conglomerate has been mainly managed by army officers, who, in some cases, have been charged with overpricing practices, embezzlement, and who have become the target of the opposing National Assembly that ended politically neutralized by Maduro.

The Big Customer

Nicaragua, who received until June 2018 over 3.760 billion dollars in oil loans, has benefited from compensation as no other country. It has been the reflection of the imbrication of Caracas and Managua government and the support granted to Daniel Ortega. Agreements with Venezuela are one of the keys that explain how Ortega’s regime got high favoritism for many years. Cooperation, among other things, helped him keep happy agribusiness organizations loyal to his party, National Liberation Sandinist Front (FSLN), and powerful local and Central American agribusinesses.

Shipments with food from Nicaragua represented 70% of the amounts traded through the compensation mechanism generating an export boom in the Central American country that gave in with the oil crisis. Beef and cattle categories were the queens, representing over 1.25 billion dollars in exports until 2017, according to BCN. Coffee, sugar, black beans, and milk have always been among the highest ranks. Shipments were monopolized by a huge intermediary: Alba Alimentos de Nicaragua (Albalinisa), a binational subsidiary of Alba de Nicaragua (Albanisa), a partnership between Empresa Nicaragüense de Petróleos (Petronic) and PDV Caribe, a controlling shareholder. Francisco López, one of the closest officers of Daniel Ortega and the Treasurer of FSLN, until June 2018 was the CEO of Petronic and Albanisa Vice-President simultaneously, where he was charged by the Treasury Department of the United States with corruption and embezzlement. He was banned from trading with American citizens and companies.

Beef meat sales together with coffee sales are shown as the main products that were sent from Nicaragua to Venezuela as payment for oil loans / MINISTERIO ALIMENTACIÓN VENEZUELA

Albalinisa was a favorite company that placed in Venezuela goods at unbelievable prices for any businessman. In Nicaragua’s Development, Industry, and Commerce Ministry (MIFIC) “preferential or superior prices”, compared to other international customers, offered by the Venezuelan government are frequently mentioned. Beef, for instance, was the best paid in 20 – 30 years, according to what René Blandón, Comisión Nacional de Ganaderos (Conagan) CEO, the largest sector association, told AFP in August 2017. Favorable quotations helped Nicaragua to pay long-term debt faster, representing 25% of the loans. It also helped it pay with goods short-term debt, representing 50% of the credit, payable within 90 days. The rest of benefited nations pay in cash, but the Central American country has insisted in paying with food, according to documents known by #Petrofraude.

Privileges for Albalinisa also included permissiveness with some products’ low quality and with intermediation of goods coming from third countries. The company enjoyed for six years a direct relation with CVAL, CASA and Café Venezuela, another public company, within the compensation scheme framework. According to documents from Venezuelan control agencies, Nicaraguan exports through 2014 were conducted without PDVSA International Finance Management drafting a single conciliation act with Albalinisa. The first two ever were subscribed, in fact, in April and August that year.

One of them referred exclusively to green coffee shipments based on data pointed out by #Petrofraude as inconsistent. The conciliation document stated that Albalinisa satisfactorily exported to Venezuela 393.6 million dollars between October 31, 2009 and December 31, 2013, according to a settlement submitted by Café Venezuela. In that five-year period, however, total shipments were less than 248.5 million dollars, according to a comparison of the figures from three institutions in that country: Centro de Trámites de Exportaciones (Cetrex), MIFIC, and BCN. Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Venezuela (INE) data, based on customs’ reports, point out that the South American country received 295.2 million dollars’ worth of green coffee. Thus, just on that, there are almost 145 and 98 million-dollar differences without any type of support or explanation respecting the reconciled amounts.

The signed minute, based on a settlement of Café Venezuela, indicates that shipments were equivalent to 1,884,796 quintals, at 208 dollars each, at least 20 dollars higher than the overseas sales price for those years, according to data from BCN and Cetrex. In 2011, for instance, just buyers from United Arab Emirates, New Zealand, and Austria beat average prices from Venezuela. Those countries are consumers of special coffees traded at higher prices.

An additional piece of data casts shadows on the transaction. According to Nicaraguan official statistics, to the South American county just up to 1.5 million bushels were shipped; according to Instituto Estadístico Venezolano, the volume was 1.4 million. Differences are between 300,000 and 400,000 bushels compared to the amounts pointed out under the settlement.

Green coffee shipped to Venezuela was far from being premium according to statements collected by this investigation. Nicaraguan producers remember that between 2008 and 2015 they sold at great prices coffee lots that had been considered waste.

“Coffee for local roasters was exported at great prices”, confirmed Joaquín Solórzano, Matagalpa Producers Association CEO, a mountainous region where most Nicaraguan coffee is produced. “They knew the quality they were buying because no one was going to complain in Venezuela”. Federico Argüello, Asociación de Exportadores de Café de Nicaragua CEO, confirmed that the Venezuelan market was particularly attractive in terms of prices: “They had a differential price higher than New York’s”.

“They had a differential price higher than New York’s” — Federico Argüello, Asociación de Exportadores de Café de Nicaragua CEO

Although Albalinisa was responsible for the shipments, some producers agreed there were intermediaries who picked up the product. One of them was Agroexport that had Venezuela as its destination on its website. A representative of the firm was interviewed but he denied participation in the business and said that reference of that country on the website was an unfortunate mistake.

While in Nicaragua producers benefited with oil pour, Venezuelan colleagues suffered with controls that sentenced them to losses and to witness the depression of the business as imports grew. “Government controlled prices were always under production costs”, said Vicente Pérez, coffee grower member of Fedeagro, the main Venezuelan producers’ federation. “Low-quality Nicaraguan coffee was paid at premium prices”.

Producers of Matagalpa, in Nicaragua, admit that they sold low quality coffee to be afterwards exported to Venezuela / JULIO LÓPEZ

Contradictory Accounts

The second document was executed to reconcile the rest of the imports that took place between June 2008 and September 2013. It was determined the amount had been 1.573 billion dollars since the settlement executed by Elio Mejías, CVAL CEO, David Mendoza, CASA Director, and Carlos Osorio, an Army General, CEO of the latter. This General was also charged by the Department of the Treasury of the United States in November 2017 for alleged corruption in the management of the food-for-Venezuela project which he has denied.

Beef was the main imported product in the period. PDVSA in its reports, never mentioned the amounts of beef cuts for those years, but Venezuelan and Nicaraguan statistical authorities report total sales of at least 682 million dollars. The oil corporation guaranteed the volume coming into the South American country was 149,084 tons. This figure contradicts INE customs’ information that reported for that year almost 20,000 tons less coming from Nicaragua. It implies a difference of at least 80 million dollars calculated on average prices beef was sold to Venezuela, according to BCN.

These trades had a very happy livestock association. Ronald Blandón, who took over CONAGAN presidency after his brother René, confirmed the trade scale handled by Albalinisa can be explained only politically: “It was a coincidence of Ortega’s and Chavez’s wills”. In addition to private businessmen, Sandinist cooperatives were also benefitted with the business. Unión Nacional de Agricultores y Ganaderos, for instance, received a small commission for each head of cattle received from members to be shipped to Venezuela, as confirmed by its CEO, Manuel Morales. Albalinisa bought in 2009 to the Seminole Tribe the largest cattle ranch in the country and the same apparently happened with other ranches that became controlled by FSLN, according to the Department of the Treasury.

These were not the only transactions that made people uncomfortable even in Venezuela. Albalinisa sent to that country goods coming from third countries which should have never taken place, according to the energy agreements. Letters sent from CASA and CVAL to PDVSA, known by Confidencial reflect, for instance, the sale of black beans from Argentina, sugar from Guatemala, and palm oil from Honduras for 25 million dollars in 2012 and 2013. In the palm oil case, General Osorio confirmed the reception of 2,984 tons at 3.9 million dollars a ton, 80% higher than what was shipped from the country of origin directly to Venezuela, according to Honduran official data.

Bernardo Álvarez, as PDV Caribe CEO, sent a memo to PDVSA presidency on November 4, 2013 asking to ban this type of operations to Nicaragua. As part of the document, he attached an e-mail of August 2013 where a CVAL officer confirmed the company had stopped Albalinisa purchases to avoid intermediations that may affect Venezuelan public equity and distort the oil agreements that framed the compensation.

The import plan authorized in March 2015 by Maduro just confirmed a habitual price practice. The proposal was submitted by Giussepe Yoffreda, Air Force General Major that had become the previous year the imports’ tsar as Corpovex CEO, an institution that received the task to centralize the sourcing duties overseas for the public and private sectors who was also charged by the Venezuelan National Assembly for his connection to alleged overpriced imports. The officer guaranteed Maduro that the plan with Nicaragua would be useful to take care of food supplies in Venezuela and to strengthen Alba and Petrocaribe’s “historically revolutionary project”. The president executed it a few days later at an unexpected visit to Nicaragua offering support if they disclosed a US national security directive that declared Venezuela a threat. During his visit, the Venezuelan President was awarded by his peer.

Giussepe Yoffreda, Major General of the Air Force, became the czar of Venezuela's imports and played a key role in the design of food import operations under the oil compensation mechanism. / CADENA NACIONAL DE RADIO Y TV

The signature of the agreement for the amounts indicated by Yoffreda was confirmed in a letter from Francisco López, Albalinisa CEO to high Venezuelan officers on November 6, 2015. “The value of the contract was 446.3 million dollars’ worth of beef, beef, milk, coffee, sugar, black beans, heifers, cows, and refined oil”, says the third paragraph of the letter that was disclosed by Diario Las Américas in November that year. Although values and volumes were not specified per item, López’s data coincided with Maduro’s guidelines.

López pointed out in his letter that the agreement was valid for the period between January through December 2015 and that through October they had invoiced 391.3 million dollars, that, contrasted with the Nicaraguan Central Bank data, it never went over 290 million dollars throughout the year and the payment of average prices was under what Maduro had authorized for beef, cattle, coffee, and sugar, what set the alarms for another differential.

The officer claimed that PDVSA had not sent 90 million dollars in oil according to the plan and that it had forced Nicaragua to seek financing in order not to stop sending food to Venezuela, a situation that López did not know how sustainable could be. The contents of the letter ratified that Albanisa paid with goods and not with cash the short-term oil financing, which was a continental exception accepted by PDVSA in practical terms although until early 2018 the oil corporation was still waiting for a board of directors’ order to open accounting in terms of that reality, according to #Petrofraude documents.

Beyond the Agreement

A trend like the commercial compensation with Nicaragua took place with Guyana, the second largest beneficiary of the system. While the People’s Progressive Party had the power in that country, that shares a border disagreement with Venezuela, it had privileged treatment. The organization likes Chávez’s policies and lost power in 2015, which caused the agreements to end abruptly.

During six years over a million tons of white rice and paddy were shipped to Venezuela in exchange of oil loans. According to calculations conducted by #Petrofraude investigation, Guyana Rice Development Board (GRDB), the Venezuelan government paid in the period at least 100 million dollars over the average price at which the Caribbean country used to sell to other international customers.

In 2010, for instance, Caracas accepted the 700 dollar per ton quotation while European Union buyers bought it for 224 dollars less.

An Interamerican Development Bank report released in 2016 expressed its perplexity for the fact that Venezuelan authorities negotiated a high-value commodity like oil for another less valuable like rice.

Venezuela was, thanks to oil agreements, the client who paid the highest price for the rice produced in the fields of Guyana / ANDREW FLECMAN

“The highest benefit for Venezuela seems not to be economic”, points out the text suggesting the profit was diplomatic through support at OAS.

The terms of the exchange do not correspond to Petrocaribe’s agreement that sets forth under clause five that goods shipped for debt compensation must have preferential prices. It is ratified by guidelines that rule issues agreed upon by member countries’ ministers.

“The highest benefit for Venezuela seems not to be economic” — Interamerican Development Bank report released in 2016.

Venezuelan agreement granting caused unrest in the sector. Rajndra Persaud, Rice Mill and Export Association CEO, interviewed for this investigation, stated that the selection of companies that participated in the compensation mechanism with Petrocaribe were mainly due to “political decisions”.

Turhane Doerga, a former industry executive and political activist, stated that the agreements were fulfilled by a handful of mills linked to the former government and that even a corporate group that lacked the experience but knew about restaurants, hotels, and gyms was granted a huge quota through Buddy’s Rice Mills Complex to start doing business with. Its agents were contacted for this investigation, to no avail.

Doerga in known in Guyana for having claimed angrily the situation at a meeting in 2014 amid rice millers and authorities who managed Petrocaribe’s agreement and for having for having filed a claim at Guyana Police Organized Crime Special Unit a claim pointing out that shipments to Venezuela not only had a scheme of privileges but fraud for shipping low-quality goods with fake certificates and overpriced export shipping costs that according to his data, were twice as high as ordinary rates and were similar to those paid for shipments to Europe.

Turhane Doerga, a former rice industry executive and political activist in Guyana, has questioned the way oil shipments were managed.

Rajndra Persaud, president of the Association of Rice Exporters and Millers of Guyana, states that political criteria deprived in the selection of businessmen that exported to Venezuela / ANDREW FLECMAN

GBRD spokespeople were contacted in Guyana and then e-mailed about their rice selling operations to Petrocaribe but they would not answer any questions. Six former directors are under investigation in that country for irregular use of funds gotten through the agreement. Two of them were interviewed but denied any inadequate management responsibility.

Donald Ramotar, President of Guyana between 2011 and 2015, was contacted for this work. He was also e-mailed to know his answers about prices agreed with Venezuela and mill selection. He never replied but, in previous statements, he has said that charges and investigations have a political nature.

The Dominican Republic and El Salvador have traded, respectively, 70 and 48.8 million dollars in the compensation system through Petrocaribe according to data from both countries. The auditing report accessed by #Petrofraude, mentions cases with overprices of at least 10.1 million dollars in items like raw sugar, soy oil, and black beans.

Black beans were shipped from the Dominican Republic in 2010. The operation involved 1.769 tons equivalent to 2.21 million dollars. Average price was 1,250 dollars per ton, almost 100 dollars over the international benchmark price. José Suriel, Petrocaribe’s Office Director in the Dominican Republic, said in 2012 to the local media that the operation was the result of a purchase to third parties, which had breached agreement terms. San Juan de la Maguana Agricultural Producer’s Association CEO, Manuel Matos, stated to journalists working for this investigation that the beans were bought in China and Nicaragua to be shipped from the Caribbean island as if they were Dominican.

Although Suriel had revealed the irregularity six years before, when contacted for this investigation, he denied it: “It was never anything beyond a rumor that was not verified through valid documentation”. According to Suriel, the selection of companies and price setting were set by Venezuelan authorities and never Dominican authorities. When the Caribbean country joined Petrocaribe, the Dominican Republic Export and Investment Center (CEI-RD) oversaw the registration and purging companies to participate in the agreement.

“It was never anything beyond a rumor that was not verified through valid documentation” — Petrocaribe’s Office Director in the Dominican Republic.

One of the main Salvadorian cases mentioned in the audit was the result of a triangulation authorized in April 2015 by Asdrúbal Chávez, Minister of energy, as requested by Eulogio del Pino and Bernardo Álvarez, PDVSA and PDV Caribe CEOs, echoed by General Yoffreda’s request.

Alba Petróleos de El Salvador (ALBAPES), recipient of Venezuelan credits from Petrocaribe in excess of 1.1 billion dollars, was authorized to explore the purchase of goods in other countries like Australia, New Zealand, and Colombia, to be charged to the compensation accounts. ALBAPES is a partnership between ENEPASA, a company founded by mayor’s offices of Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, and PDV Caribe, that controls most of the shares.

The transaction mentioned in the audit report became reality through a shipment of milk that, according to the oil company was overpriced 2.6 million dollars, thus harming PDVSA. The fact that it had been authorized from a third country, was considered a breach to the agreement purposes.

Although no other details are provided, the media contributing to #Petrofraude verified customs’ data in El Salvador. A series of milk shipments to Venezuela in 2015 took place in that country totaling 991 tons for 3.2 million dollars, implying at least a million dollars over international averages, according to our calculations.

The information points out that the goods were bought in Australia. Corpovex does not appear as recipient, but another state company the process took place for: CVAL. Albapes does not appear as shipper, either, but an unknown company called Proveedores Diversos A&G, responsible of the shipment.

Journalists who worked for this investigation visited the legal address registered by the company and found a house in a middle-class settlement in Santa Tecla, La Libertad, rented by a family who stated that no company has operated there for the least two years, at least.

There is no organization working at the facilities of the headquarters of the company that sent milk to Venezuela from El Salvador / MELVIN RIVAS, LA PRENSA GRÁFICA EL SALVADOR

Its previous legal address was verified, as well, and it is another house in Lourdes neighborhood in San Salvador where the dwellers stated the company does not operate there, anymore. Proveedores Diversos A&G was founded in 2010 with a capital of 6,000 dollars. Sonia Alas and Francisco Gallardo, company shareholders, contacted for this work, would not make any comments on milk intermediation, connections with Petrocaribe, and company capital gains of over three million dollars.

Privileged Relations

PDVSA auditors did not get deeper into the political relations of some of the businessmen involved. One case is related to Abonos Dominicanos (ABODOM), founded in September 2013 and that the following year shipped to Venezuela 2.58 million dollars’ worth of defluorinated phosphate, a product commonly used to feed poultry. For the operation moment, two company shareholders, Ángel Estévez and José Ramón Peralta, were outstanding directors of the government’s party, Dominican Liberation Party (PLD). Estévez, an agricultural businessman who has been a public servant since Medina got into power in August 2012, first as Banco Agrícola CEO, then as Minister of Agriculture, and recently as Minister of the Environment, is Abodom shareholder through Comesa; it has been stated by him under oath.

Peralta, Administrative Minister of the Dominican Presidency since 2012 and the right hand of current President Medina, is Estévez’s partner in Abodom. The businessman who became public servant has been a shareholder of the company all along, first through Agrotécnica Central and since 2016 through Inversiones Siracusa. Neither one answered our interview requests for this investigation that were processed through their respective communications teams.

José Ramón Peralta (left) and Ángel Estévez (right) are government ministers of President Danilo Medina of the Dominican Republic and members of a company that sent goods to Venezuela under the umbrella of Petrocaribe/ PEDRO JAIME FERNÁNDEZ, DIARIO LIBRE REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA

The Dominican Republic also used the compensation mechanism for companies with branches in Venezuela. One of them was Productora Panorama that shipped 17 thousand tons of pasta for 28.1 million dollars. According to this investigation, the operation was an intermediation. This was confirmed by Rafael Espinal, who was the head of Petrocaribe Office in the Dominican Republic. "Productora Panorama was a trader". According to the official, the company bought products locally and then they were packaged and re-shipped. In average, each kilogram was sold at 1.65 dollars, comparable to the price Venezuela paid to Italian manufacturers during the period, according to INE data.

Productora Panorama, according to data submitted by the Intellectual Property National Office shareholders, is owned by a Venezuelan businessman called Fran Carlos Rincones. His name appears linked to other companies with Tomás González, who has been one of the most important intermediaries linked to million-dollar sales of food to PDVSA subsidiaries. Both are linked through Grupo Pacific Internacional, based in Panama, being one of ten companies, the businessman has registered in that country. In Caracas, Rincones is partner of Alimentos GRS founded in 2010. The company, according to its acts, was founded in an act that had as assistant Karen Leyre Ortega, a former Food Ministry of Venezuela employee, with Osorio as her supervisor, and who became shareholder in 2012. Productora Panorama branch in Santo Domingo was visited by journalists for this investigation, but no corporate agents were ever found.

A case like Abodom was aired in November 2015 in Surinam, where Jubosa Group was linked with Winston Lackin, who, until August of that year had been President Desi Bouterse’s Foreign Affairs Minister. The company was favored in March 2015 being granted an agreement to ship, through the compensation scheme, 15 million tons of rice for about five million dollars to Venezuela. According to local media reports, the Jubosa Group Director was Lackin’s brother. Charges were pressed by parliament member Asiskumar Gajadien who also stated that payment given to producers was minimal, contradicting Petrocaribe’s spirit.

Lackin, who in public speeches became Petrocaribe and Alba advocate, replied to the accusations in a statement that offered to a local TV broadcaster, now available on Youtube. The message denied responsibilities and that as minister, he enabled the existence of the agreement with Venezuela but never spoke about his brother. About Gajadien, he said the following: “What that man said is senseless”. Parliament was contacted by journalists of this research, in writing, to no avail. Jubosa Group operation was directly authorized by Maduro, according to auditing documents accessed by #Petrofraude. The operation was also in charge of General Yoffreda at Corpovex.

Sources linked to the performance of the compensation transactions stated that when the mechanism started it lacked clear rules. “It was corrected over time”, stated Rafael Espinal, who was Petrocaribe’s Director in the Dominican Republic. Espinal stated that the Venezuelan government lateness to send the agreements to pay those involved influenced local businesses to increase prices. According to PDVSA, agreements took as long as a year and a half.

The millions of dollars distributed in magnificent deals at amazing prices, according to interviewed producers in benefitted countries, created a temporary bubble that is over now that oil prices have plummeted. In Venezuela, producers of milk, rice, beef, and coffee feel they got nothing out of the boom days and now they do not contribute much to feed Venezuelans.