OLP: The mask of official terror in Venezuela

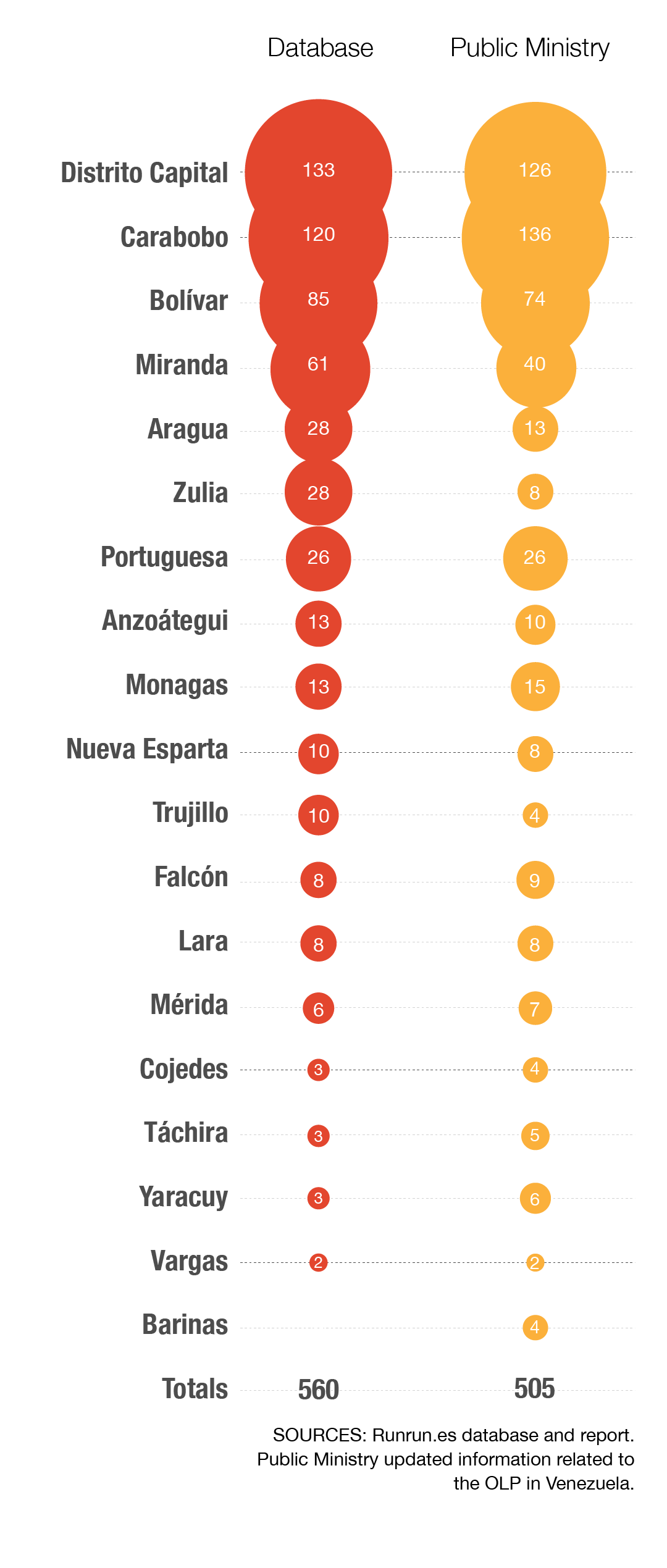

At least 560 people were killed in Venezuela during the implementation of a citizen security policy called Operation to Liberate and Protect the People (OLP): a plan to “combat crime and especially Colombian paramilitaries,” according to President Nicolás Maduro.

From July 2015 to June 2017, forty-four massacres and systematic violations of human rights were committed during OLP raids. The operation was used to replace criminal groups by colectivos. It was also used to protect the interests of government officials and to seek personal vengeance. American citizen Joshua Holt is one of the victims of the OLP. He has been detained for more than a year, without trial.

*The names of the victims were changed for their safety.

The policy was supposed to restore peace to the residents of popular sectors by “freeing” them from the oppression of criminal gangs. A “reserved” document from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Justice and Peace, obtained for this investigation, defines its security plan: “The Operation to Liberate and Protect the People (OLP) was activated in July 2015 to combat crime and, especially, paramilitarism, a Colombian practice that has been imported to destroy the peace in Venezuela and, with it, to put an end to the Bolivarian Revolution and its social achievements”.

But that promise was not fulfilled. On the contrary, what the collected data and interviews suggest is that after OLP operations there were changes of “government” (power) in the territories where different Venezuelan criminal groups operate, including members of the public force and powerful figures. The terror and anxiety among the people who live in the less privileged areas are now seasoned with new ingredient has: fear of the OLP.

“My son was sent to put on his clothes and he was shot in the heart”

With real testimonies, this video reconstructs the horror lived by the victims of the OLP

Crime increased. In 2016 there were 21,752 homicides, 12 percent more than the previous year, according to the annual report of the Public Ministry. In addition, the alleged plan of the OLP to persecute Colombian paramilitaries who allegedly operated in the country didn’t have any impact, among other reasons, because in Caracas everyone knows that there are no such irregular groups.

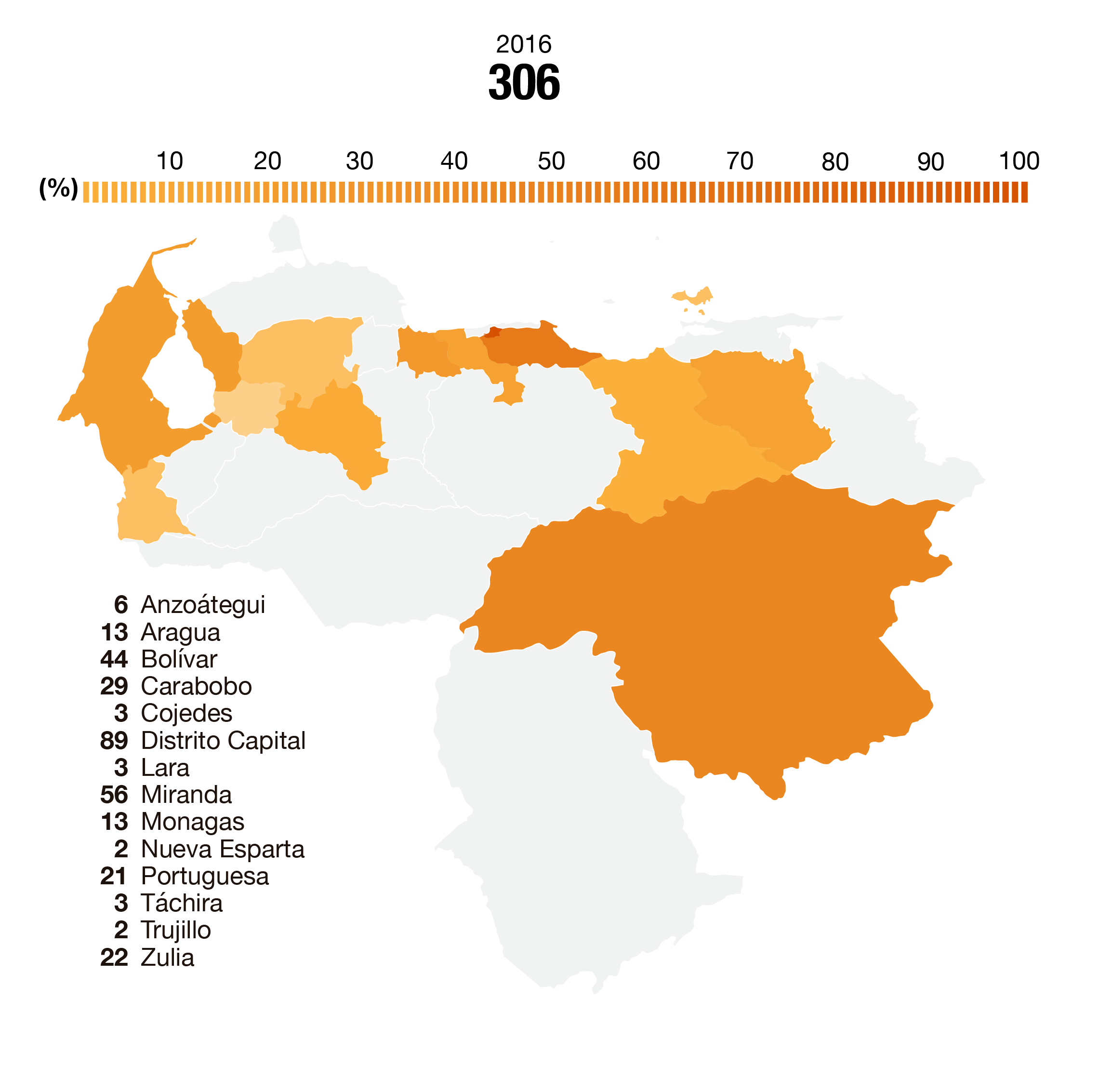

In the border states of Táchira, Apure, Barinas and Zulia, where criminal organizations known as bacrim (an offshoot of the defunct United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia) do operate, there was almost no OLP activity: 6.7 percent of the total victims of their procedures lived there. The document Public Prosecutions related to the OLP in Venezuela and the data collected by the Runrun.es team show that 99.2 percent of the victims of these operations were of Venezuelan nationality and less than 1 percent were foreign.

OLPs were selective operations. They were aimed at previously chosen people. Public security officers carried mobile phones and tablets with photos or names of the alleged offenders they were looking for. They also used drones and prostitutes to identify and locate them. Although in its beginnings the motivation behind the procedures was to bolster propaganda, in the months leading up to the parliamentary elections of 2015, these operations were used to seek personal vengeance, to capture territories and give them to pro-government gangs or colectivos, and to powerful people.

The improvised plan was out of control from the start when 15 people were reported dead after the first OLP was carried out at Cota 905, southwest of Caracas. There were also allegations of destruction of property and theft at homes searched without a warrant. These abuses and systematic violations of human rights were recurrent in all the procedures. Testimonies of victims and perpetrators as well as rigorously checked documentation, show that 44 massacres were committed in silence. Despite the fact that the OLP operations were spectacular and included armored vehicles, helicopters, weapons of war, electronic devices, drones and masks of death, 338 people of the 560 killed didn’t receive any media attention.

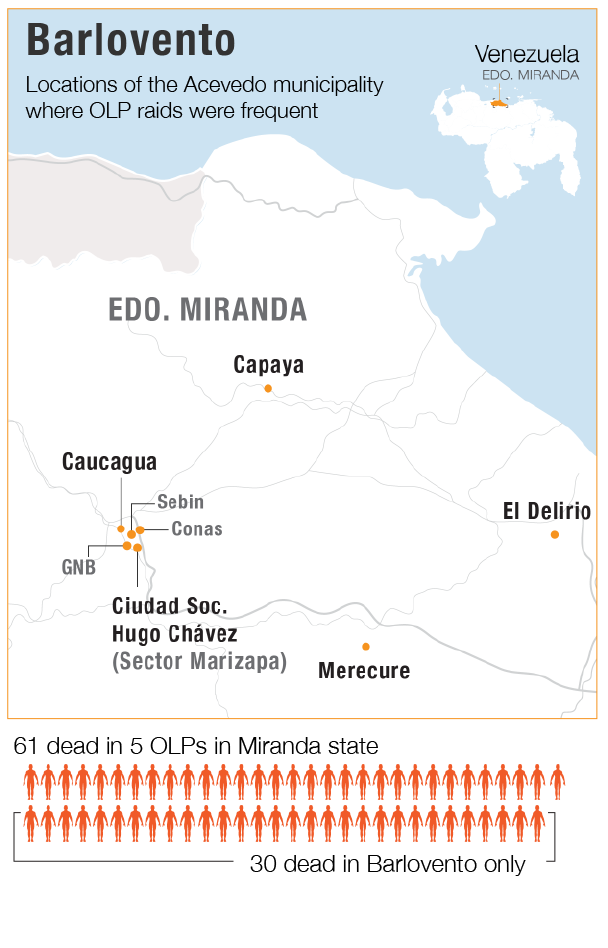

Researcher and professor of the Central University of Venezuela (UCV), Keymer Ávila, described it as a “drip massacre” covered with terrifying masks that had a greater impact than the deaths of hundreds of Venezuelans themselves. Only the Barlovento massacre, which occurred at some point between October and November 2016 (12 men went missing for 40 days and found dead), captured the public attention and became a scandal, although authorities took pains to exculpate the OLP.

Kimberly’s son is 9 years old and no longer believes in Baby Jesus (Venezuelan Santa Claus). They live in Capaya, a small town in Barlovento, in the state of Miranda, 81 kilometers from Caracas. In December he asked Baby Jesus to bring him a telescope and his dad so they could look at the stars together. But the magical character, who was actually his mom, had become a young widow a month before and did not have the money to buy the toy, nor the power to bring his husband Freddy Hernández back to life. “He was taken away on October 16, 2016. He was beaten out of bed. They broke in and destroyed everything. They said it was the OLP,” the woman said.

Forty days later, on November 26, Freddy’s body was found in a mass grave next to the corpses of 11 other men. They were the victims of the Barlovento massacre. Kimberly wipes the tears from her face, and thanks the help she has received from the community, because her husband was the sole support of the family. He worked as a motorbike taxi driver and a mechanic.

The massacre was carried out by officers of the Batallón Caribe del Ejército, a military unit used to controlling irregular groups at the border. They had been transferred to this area from the center of the country in April and May 2016 to support the OLP. They stayed there and improvised a command in an abandoned house in El Café village, neighbor to Capaya, both located in the municipality of Acevedo in Barlovento.

The victims were taken from their homes or public transport or detained on the streets in different procedures. Most were released after being tortured for a week. But the 12 men who remained in prison were executed and disappeared. The pressure of the relatives forced the authorities to investigate and the corpses were found mutilated and buried 40 days later. The 18 soldiers responsible for the crime were arrested.

"They always said that it was a presidential orden... that it was the OLP with a presidential order"

The government offered a compensation to the wives of the victims and old-age pensions to the parents. But at Christmas, a month after the bodies had been found, the relatives received the only support the state –which was responsible for the executions–, conceded to give them. “We were given a bag of CLAP (the food that the government sells), a toy for each child and a backpack with some notebooks and crayons for school… But what good is that? That does not bring him back to me. We had plans, we thought we were going to get old together”, describes the young woman sitting on a bench in front of the village church.

Standing at the gates of his command in Caucagua, the capital of the municipality of Acevedo, an officer explained what the OLP was for. He wore hiking boots, plaited to the calves, over his olive trousers, and a black flannel with his name embroidered on the upper left. He set his foot firmly against the dirt floor, lifted his heel, without taking off his shoes from the ground, and slowly moved it from left to right, as if crushing a cockroach. Then he replied: “The OLP? The OLP is like this. It’s like stepping on an anthill.” He paused, rummaged in his memory and said a number: “We’ve killed up to 15 in a procedure, but in two weeks other 30 come out…”

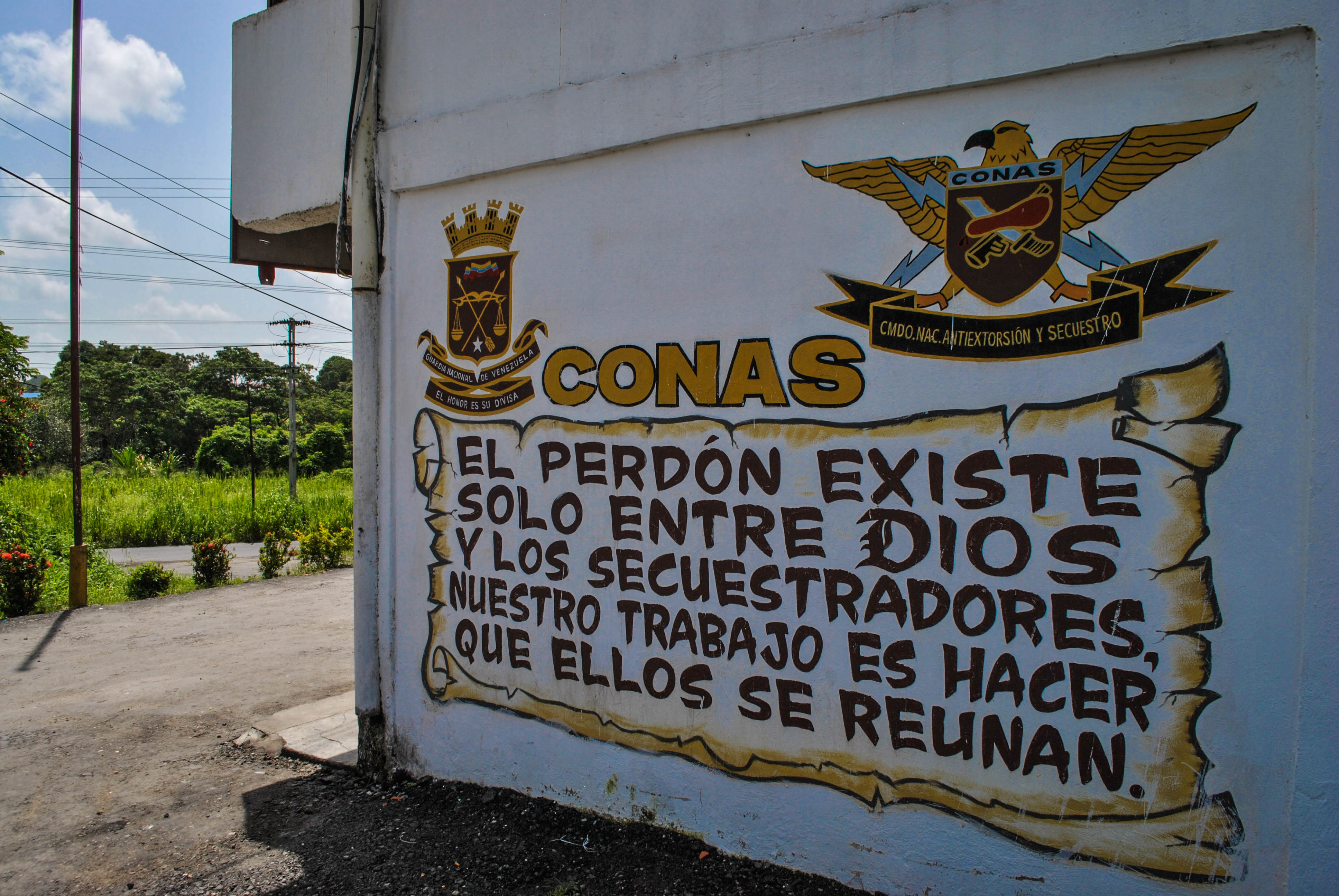

The officer, who spoke on condition of anonymity –not because he was ashamed of his actions, but for fear of being punished–, is a member of the National Anti-extortion and Kidnapping Command, CONAS) of the National Bolivarian Guard (GNB), one of the security bodies involved in the OLP. His final words are not a metaphor. The OLP has killed more than 560 people in Venezuela in two years, according to data collected from the press around the country. The figure is barely higher than the 505 reported by the Attorney-General’s Office of the Public Ministry.

Inscription on one of the walls of the Conas headquarters –one of the most feared security forces– in Cacagua.

The OLP has been the latest move by the government of Nicolás Maduro to end criminality in Venezuela, the second most violent country in the region –only surpassed by El Salvador–, with 21,752 murders in 2016 and a rate of 70 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. On August 3, 2015, before a group of guests -incidentally from the Central American country– and a hundred military and cabinet ministers, Maduro said: “The OLP is the perfect instrument for achieving peace from within”. In the same speech he urged “to act head-on, without hesitation” against criminals. The procedure was entrusted to the Ministries of Defense and Interior Relations, Justice and Peace (MRIJP).

Nicolás Maduro says that the OLPs are a perfect instrument to achieve peace.

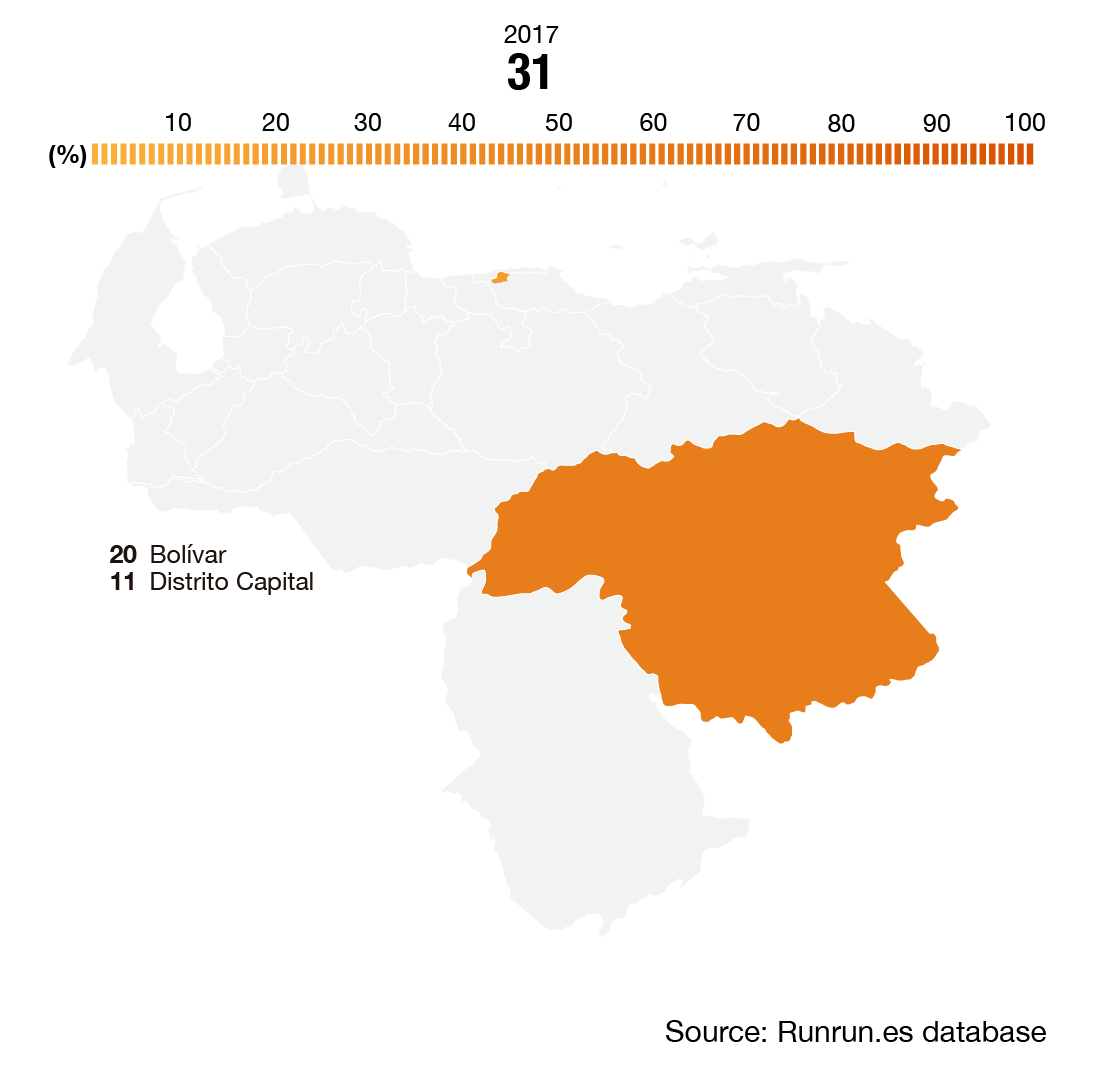

The testimony of a score of victims gathered for this investigation, in journeys made to the five regions that recorded the most OLP killings in the country (Capital District, Carabobo, Bolivar, Miranda and Aragua) contradict the President. The OLP did not bring peace to their lives.

Pain and misery was the legacy of the OLP in the family of Alex Yorman Vegas. More than six months have passed but he bursts into tears when he remembers the day in which the OLP killed Alex, his only son. “My son was murdered on March 10. Approximately at 6:30 in the morning the Bolivarian National Police came in the house, the so-called “men in black” (Special Action Force of the PNB), some hooded, others not. They opened the door with a mandarriazo (beating it with a mallet). My wife, my daughter and I were forced out, practically naked. They spent half an hour with my son in the room and beat him. They told him to get dressed, because he was sleeping, and brought him down to the living room. They gave my 16-year old boy a single shot in the heart, without any reason… They killed my boy like that”.

Alex continued with his story making pauses from time to time and blaming himself for not saving his son. “I tried to go upstairs to help him, but one of the policemen told me that if I got funny, they would give me some tubazos (shots)… If I had known they were going to kill him, I would not have left him. They would have had to kill us both”. While the policemen beat his son in one of the rooms of the house, in Los Jardines de El Valle, a modest area southwest of Caracas, Alex was put in an official vehicle and taken to two police stations along with his 11 year old daughter and his wife. Isolated, uncertain of what was happening and arrested without a warrant or the presence of a public prosecutor, they remained in there for six hours. “I had to beg a policeman, because my little girl needed to pee and they would not let us go to the bathroom”.

Shortly after midday he learned that his son Alex Vegas was dead. The police remained in his house until 2 in the afternoon. In addition to having killed the boy, they stole the family’s belongings. From the food in the fridge to the clothes and electronic equipment, everything was taken from the apartment. “They didn’t find any drugs, they didn’t find any weapons. I’ve never had any problems with the law, nor my kid”. He kept telling his story outside the government department where he works, and recalled that the PNB was accompanied by officers of the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM), who covered their faces with skull masks. They say they wear them to protect their identities, but it’s actually to intimidate people.

Victims of the OLP

Comparison of totals by state according to the database of the Public Ministery and Runrun.es

Officers arrived at the barrios at dawn, wearing skull masks and black clothes

Photo: Felipe Romero. Courtesy of Caraota Digital

Officers of the OLP used to cover their faces with balaclavas or wearing masks with skulls, known as “death masks”, similar to those used by the characters of the war videogame Call of Duty. Commissioner Luis Godoy, former head of the Division of Homicides of the Judicial Police (now Bureau for Scientific, Criminal, and Forensic Investigations, CICPC), explained that this practice violated police regulations, according to which police officers should wear visible badges and not cover their faces. “Those wearing these masks want to show people that they are a police force ready to kill. They want to frighten, to cause terror. That is not the purpose of a state agency”, said the former police officer, adding that the visual effect is completed with the black clothes worn by OLP officers. After the media scandal, Commissioner Douglas Rico, head of CICPC, issued a statement prohibiting the use of masks. However, as revealed by one of his subordinates, the officers were ordered to wear similar clothing –without covering their faces– to patrol the neighborhoods of Caracas with long guns during the 2017 protests, as a deterrent and intimidation mechanism for those who wanted to demonstrate on the streets. The state terror did not end with the killings. Alex says the policemen who murdered his son have already been identified: he could see them in the file of the case at the Attorney-General’s Office. He’s been privileged, since most of the relatives of OLP victims have not been able to have access the judicial reports, autopsies and death certificates of their children or spouses.

After his son died at the hands of police, Alex devotes his only free day to seek justice. He doesn’t go to the beach or the movies, nor does he stay home and play with his daughter. “I go to the Attorney- General’s Office every Monday to see how my son’s case is going. It’s my free day from work. The prosecutor tells me that the policemen who killed my son have already been identified, but have not shown up and there’s nothing he can do about it. He tells me not to worry because those crimes do not prescribe.”

"They have a detention order, but they haven’t put them in jail yet ... I go to the Attorney-General’s Office every Monday, because Monday is my free day”

Ever since the first appearance of the OLP on July 13, 2015, when a new procedure is carried out, the complaints and descriptions of abuse from those affected coincide. This repetition in the modus operandi of the security forces has led citizens to identify, name or report as OLPs any procedure that brings together members of different police and military bodies and operates under the same patterns of terror and human rights violations, even if they have not been sent by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Justice and Peace.

“The OLPs represent the most repressive security operation in the history of Venezuela,” says Luis Izquiel, a criminal lawyer, criminologist and former prosecutor at the Attorney-General’s Office. “It has the highest rate of police executions and house raids, as well as reports of theft and property destruction. During these operations, entire neighborhoods such as La Ensenada in La Rinconada de Caracas and Brisas del Hipódromo in Carabobo have been knocked down. These improvised and selective executions penalize poverty. Most victims belong to poor sectors and criminals are not precisely captured. Nor have these operations helped to reduce crime,” says the expert.

The results of this security plan are far from being successful. In addition to the increase in homicides, crimes such as kidnapping and extortion (of which there are no official figures) did not stop. “The kidnappings were almost halved in the first six months of 2017, basically because of the closure of roads due to the protests. But crime continues to occur. We have reported about 230 cases,” said an official of the Anti-Extortion and Kidnappings Division of the Scientific, Penal, and Criminal Investigative Corps (CICPC), who asked not to be identified because he is not allowed to give figures to the press.

The National Guard’s Anti-extortion and Kidnapping Command (CONAS) in Caucagua, receives up to four reports in a week. Inside its headquarters, two women were filing a kidnapping complaint, and one officer was on the phone, informing his superior about the progress of an investigation involving a national guard. “The man lent his phone to the kidnappers so they could make the ransom calls,” he explained.

In addition, the OLP as a procedure has been marked by allegations of human rights violations, such as summary executions, arbitrary detentions and torture, as reflected in the Attorney-General’s Office’s report on the OLPs. According to this document, 357 investigations were opened for homicides allegedly committed by law enforcement officials, and 77 for violation of domicile, abuse of authority, destruction of homes and cruel treatment or torture, among others.

The accounts of these police excesses and violations of Human Rights are repeated in almost all cases. Mariana’s brother* is one of the survivors of the Barlovento Massacre. “They took him from the house. They came in breaking down the door and they knocked him out. He was imprisoned for a week and when he was released he could not even walk. They tortured him, told him that he was a garitero (an expression used to identify gang members that alert the arrival of the police and protect the leader of the band, also known as pran), that he was part of a gang, that he was hiding weapons. It’s a miracle he’s alive. They even put him electricity”, she said, pointing to the area of the testicles.

Capaya is one of the towns of the municipality of Acevedo, Miranda state. Five of the victims of the Barlovento massacre lived there

Carlos*, another survivor, tells his story: “We were around 30 in a small cuartico like this (a 2 by 2 meter room). We had to take turns to sit down and we urinated in Coca Cola bottles, because they wouldn’t let us go to the bathroom. When they knew the prosecutor was coming, they handcuffed us all and took us walking to a lagoon on the hill. They left us there for up to four hours. When the prosecutor arrived they told him that they had no prisoners. At night I could hear Eliecer’s screams when he was being tortured. I knew it was him, because they said to him: ‘Aren’t you officer? Aren’t you a macho?’” He was referring to Eliecer Yustaris, a Navy reservist who was taken from his home in Capaya.

Twenty days after the disappearance of Danny Acevedo Vahamonde, a group of soldiers visited his parents. “They told us that Danny had already been released. And asked us whether we’d received a ransom call because surely he had been kidnapped by crooks after his release. It was a lie, because we got tired of waiting for the call. Imagine, we do not even have a telephone”, says Neida Josefina Vahamonde, sitting in the living room of her humble house in Capaya, where she has an altar with the photo of her murdered son.

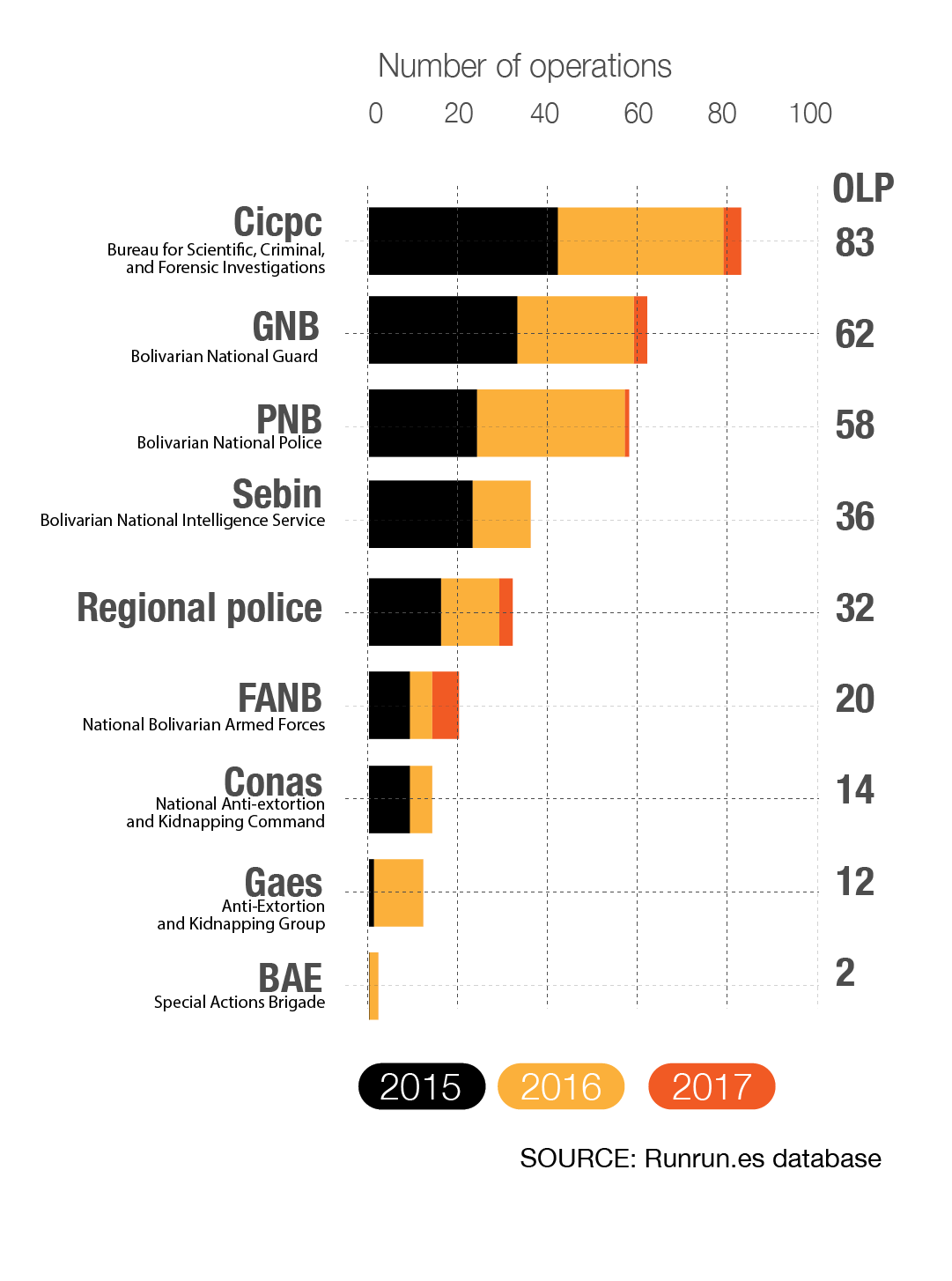

Involment of security forces in OLP raids

Following the discovery of the bodies, the Interior, Justice and Peace Minister Néstor Reverol and the Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino spoke out against the massacre and announced the removal and detention of the 18 soldiers involved. The pressure of the Attorney-General’s Office –which by that time began to distance itself from the government–, was the key to ensuring that the case was not concealed.

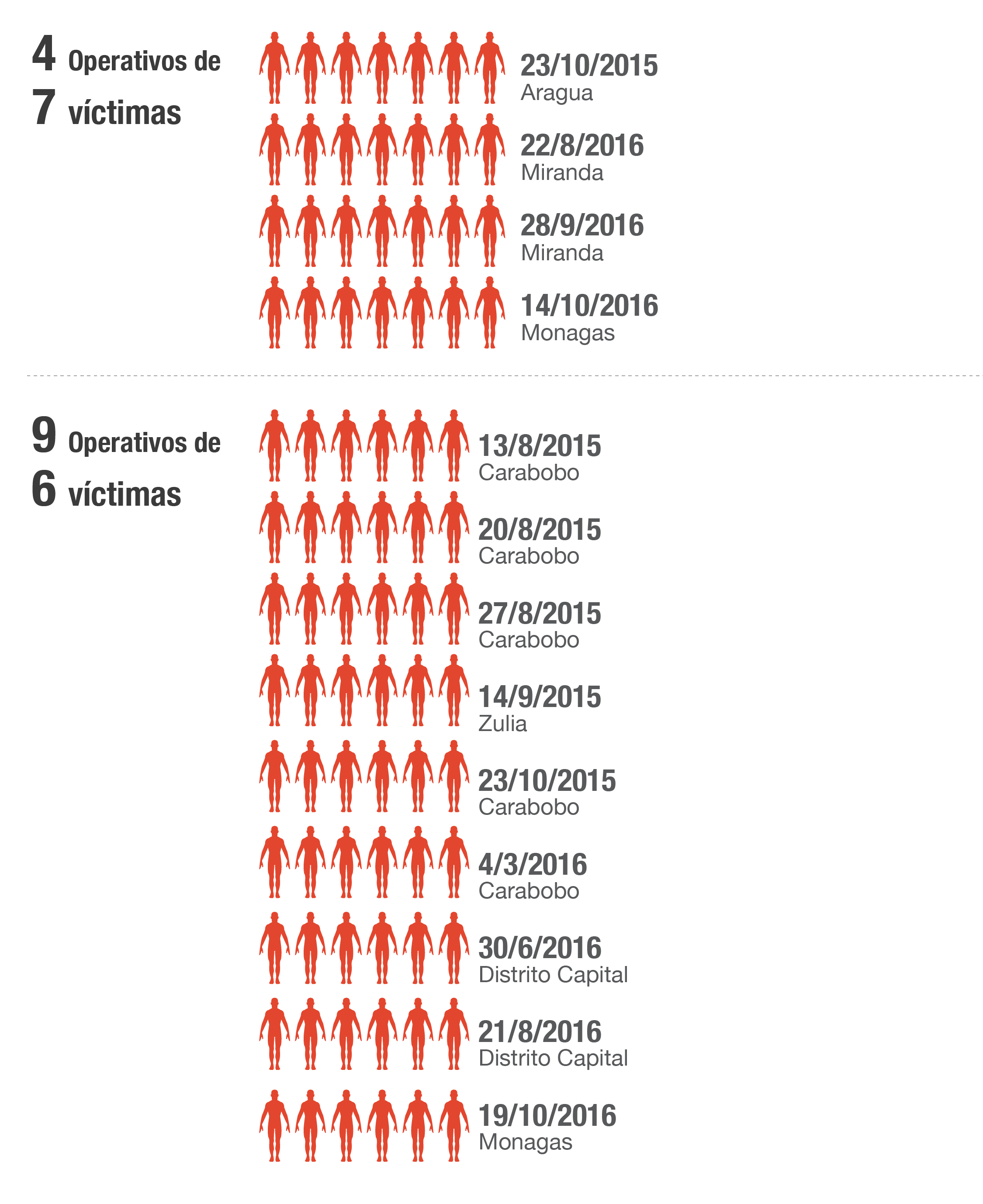

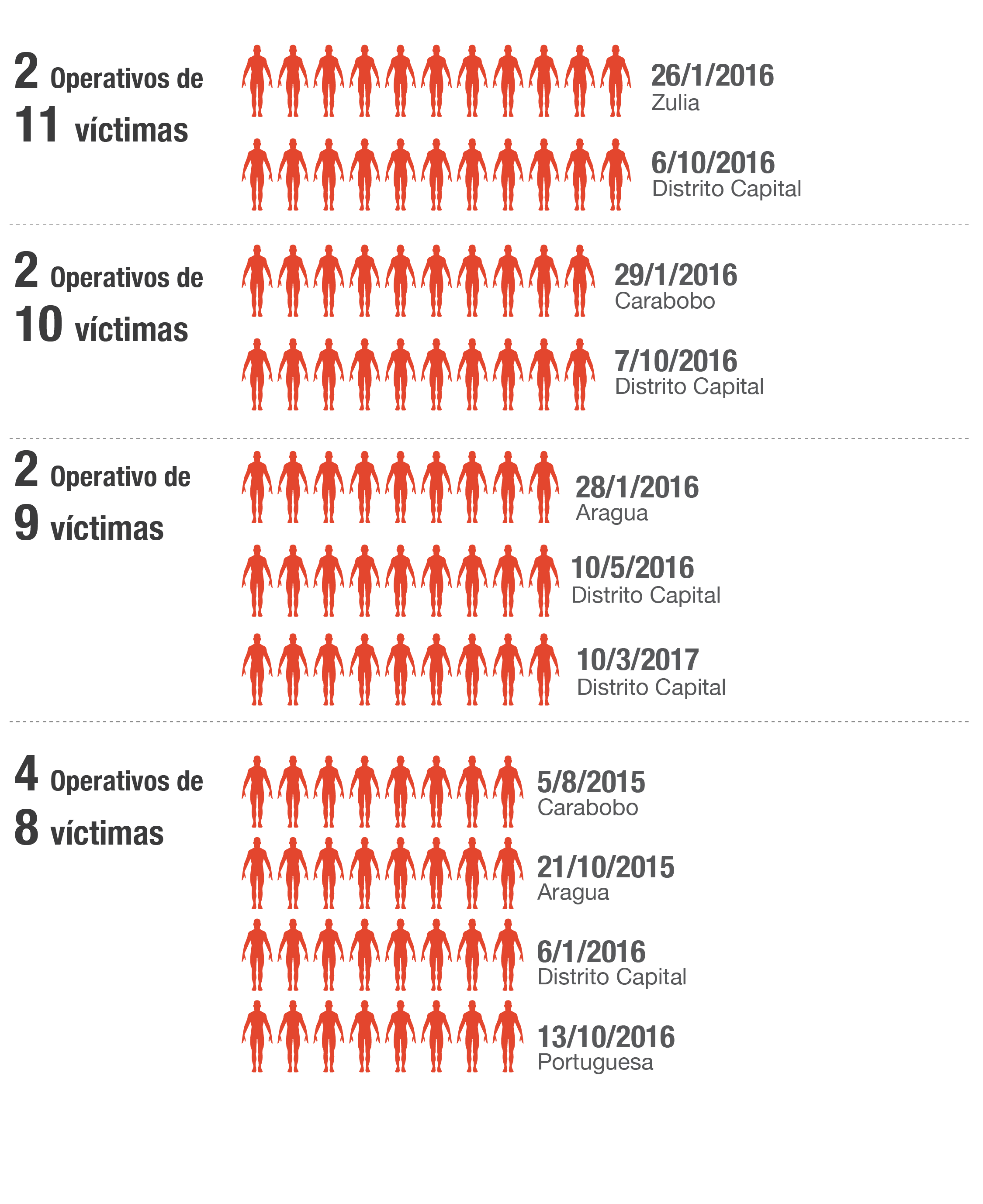

OLP Massacres

Each of the 44 operations left 5 dead or more, making a total of 338 victims

The irregularities committed by the OLP are consistent with those described in the report published in August 2017 by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on the violations perpetrated by the Venezuelan State during this year’s protests. Many experts asserted that there is a similar repression pattern in the OLP and public order actions to control demonstrations: the enemy is pursued and treated as an enemy of war.

The UN document states that in a majority of detention cases (during the 2017 demonstrations), “detainees were often subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and, in several cases documented, the ill-treatment amounted to torture… One of the most egregious cases involved the use of electric shocks… Some of the most serious cases identified by OHCHR took place on the premises of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) and the Directorate General of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM) in Caracas, and garrisons and other facilities of the Bolivarian National Guard (GNB)”. These three security forces have also had a leading role in the OLP, where the victims have reported similar mistreatments.

Executions mount

After the implementation of the OLP in 2015, deaths at the hands of security forces increased 70 percent over the previous year. In 2016 the increase was of 163 percent compared to 2015. According to these data from the Attorney-General’s Office, 22 percent of the murders in Venezuela in 2016 were the responsibility of state security forces.

The numbers presented by Liliana Ortega, director of the Committee of Relatives of Victims of the Caracazo (COFAVIC), an NGO that has worked with the cases of the social uprising of February 27, 1989 in Caracas, are even more alarming. “The first half of 2017 has been the period with the most extrajudicial executions in Venezuela (the register began in 1989), with 856 cases. This could be related to the impact of the OLP and to the fact that political repression has taken full advantage of the situation and lowered the visibility of cases of violence behind the excuse of public safety,” she explains. Enforced disappearances have also become increasingly common: they grew 533 percent from 2015 to 2016.

This video corresponds to an extrajudicial execution that took place in 2017 in Venezuela. Although it didn’t happen during an OLP raid, the large participation of officers from different police and military bodies is similar to OLP operations.

Accustomed to impunity, officials of the force proceed without any modesty. “You better leave it like that if you don’t want to end up like your brother.” The family and direct witnesses of the murder of Irving Joel Acosta Pérez, 22 years of age, decided to remain silent after an officer of the Bureau for Scientific, Criminal, and Forensic Investigations issued that threat. “They had to leave it in the hands of God or they would’ve lost another kid. If they carried on, the men would have picked on them… And what could they have done then?” said a resident of La Manga de Tumeremo, a mining area in Bolivar state, who avoided telling his name. Months after the murder of Irving Joel, the same uniformed men that killed him still prowl the area. The residents, who do not forget what happened, feel they’re being watched.

The media portrayed the killing of Acosta Pérez, known as “el gringo”, as the result of a confrontation after a search conducted by the scientific police. Witnesses, however, said that what happened in that house of Sifontes on February 19, 2017, was an extrajudicial execution at the hands of the OLP.

The incident is not on the records of the report of the Attorney-General’s Office related to the OLPs in Venezuela that runs from July 2015 to March 2017. However, the whole procedure was similar to the already observed pattern: around 6 in the morning officers forced the door and broke into the house where eight people lived, including three children less than six years.

Tumeremo, the mining town where 17 miners were killed in 2016, is still witnessing death and massacres, some executed by the OLP

The incident is not on the records of the report of the Attorney-General’s Office related to the OLPs in Venezuela that runs from July 2015 to March 2017. However, the whole procedure was similar to the already observed pattern: around 6 in the morning officers forced the door and broke into the house where eight people lived, including three children less than six years.

“They came only for him, because that was the only house they visited,” said another neighbor. According to his account, Acosta Pérez’s brother, brother-in-law and sister were taken from the place. She was the mother of two of the little ones and did not even have time to grab the three-month-old baby who slept in his crib. Shortly after, the children were taken out too. Gringo’s mom, however, was still in the house when the shot rang.

When he was killed, “el gringo” had been on parole for only three months. He had been released on November 2016, after two years and 10 months behind the bars accused of robbery. He had to report to the authorities every two weeks. After leaving jail, he had not engaged in any trade and had not even returned to the mines where he had worked before being arrested.

The researcher of the Central University of Venezuela (UCV), Keymer Ávila, said: “Operations like the OLP have a double criminal effect, increasing criminal behavior committed by state officials themselves. They are driven by a logic of fighting the enemy, and violence against the enemy becomes the natural thing. It ends up justifying the death of an alleged offender and this behavior may target any citizen.” That statement also explains the repressive attitude shown by the security forces during the protests of 2017, where according to the UN, 27 demonstrators were also executed.

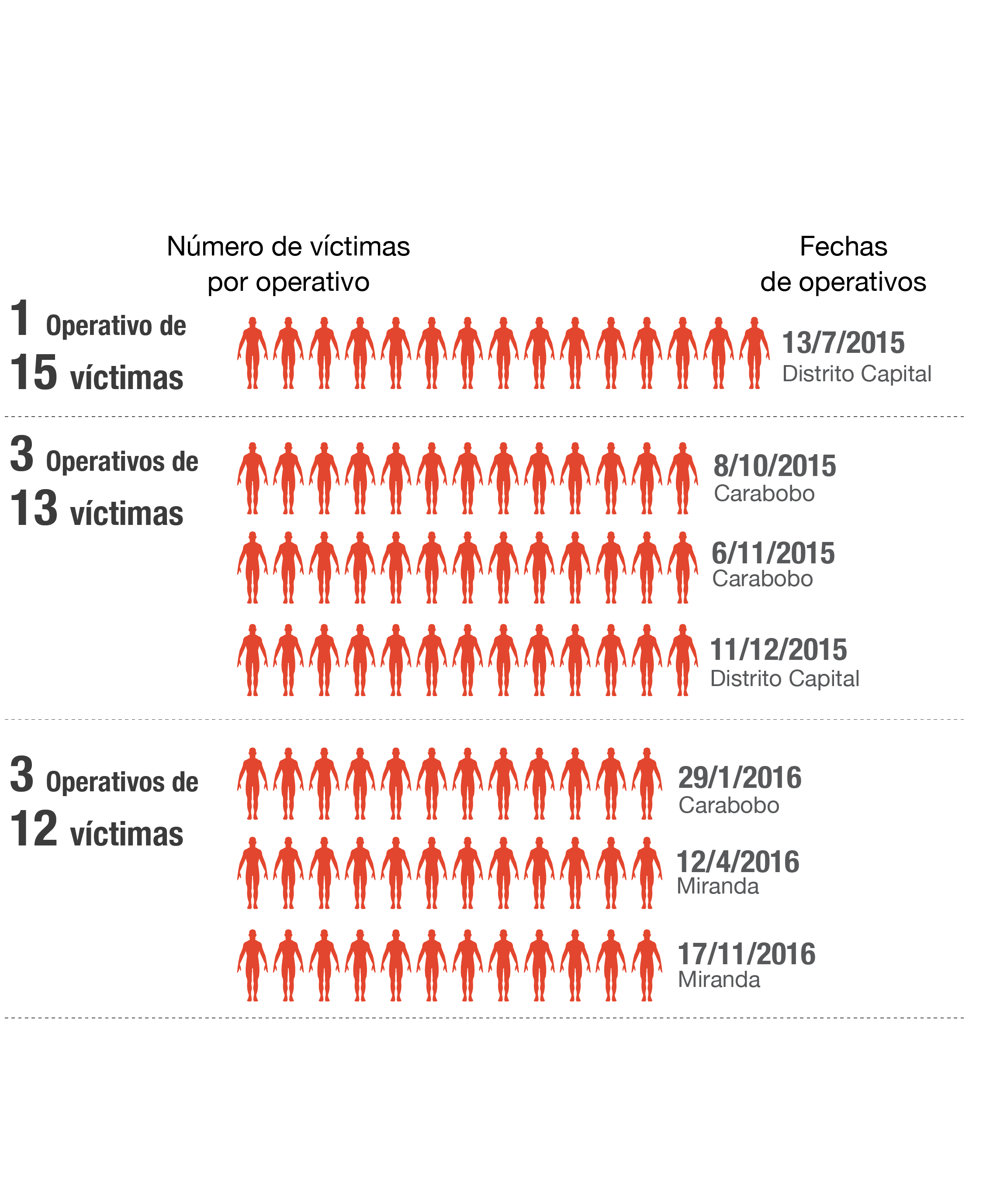

Colectivos replace criminal gangs

According to local police authorities, Mañonguito, on the outskirts of Valencia, Carabobo’s capital, used to be a territory of gangs dedicated to robberies, thefts, kidnapping, extortion and drug trafficking. After the OLP of August 2015, crimes continued but actors changed: the criminals were displaced or mutated into civilian or collective paramilitaries.

The arrival of the colectivos in Mañonguito is related to the territorial occupation of pro–government groups that acted like clash groups during the protests to deter the demonstrations taking place precisely in the north of Valencia. “Not only did they took over the territory but also over the business of criminal gangs, such as kidnapping, extortion and robbery. In short, they exercise political and social control of the recovered area,” said sociologist and expert on violence, Veronica Zubillaga.

“Mañonguito, zone of peace” can be read on a block wall at the entrance of this northern neighborhood in Valencia, Carabobo state, which owes its fame to its high crime rate. After the OLP, it came under the control of colectivos.

Colectivos are groups of armed civilians with a paramilitary structure. Some have had the support of the Venezuelan Government since the times of Hugo Chávez. Sometimes they are used as public control and “citizen security” repressive forces, and none of their activities are regulated by any legislation. Some groups are engaged in criminal activities, such as extortion, kidnapping and food smuggling. They impose their own rules of social control in the areas where they operate, and are responsible for the Local Committees for Supply and Production (CLAP). They also control the informal sale of basic products and private security services to businesses. In the past, some received foreign currency assigned by the government’s exchange control unit.

Luis Cedeño, director of the Organized Crime Observatory, described these groups as mercenaries coming from state security forces, colectivos or gangs that are paid to generate violence. He considers them within a scheme that resembles ‘mercenary terrorism’, paid for by interests that seek to create chaos”. In Mañonguito, that would be the regional and central government.

Armed groups operating in Venezuela

In Mañonguito, the colectivos did not arrive alone. The OLP was carried out by a mixed group of officers from different state security forces who cleared the ground and left the territory in their hands. Those participating forces were: the National Bolivarian Guard (GNB), the Bolivarian Army, the Anti-Extortion and Kidnapping Group (GAES), the GNB’s National Anti-Extortion and Kidnapping Command (CONAS), the Bureau for Scientific, Criminal, and Forensic Investigations (CICPC), the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN), the Carabobo Police and the Bolivarian National Police (PNB).

“The best thing that could happen to Mañonguito was the arrival of the colectivos” said a vegetable vendor while spreading her hands in front of the local church. “Everything’s quieter now and Barrio Tricolor and the government support us with building materials and small loans to fix our houses” she said, while glancing briefly at a neighbor who all of a sudden came to ask something when she saw her surrounded by strangers.

“The OLPs do not come here anymore, nor the police or anything. They’re no longer needed,” said a young man behind a stand of withered vegetables, on Mañonguito’s main street. He’s hanging out with friends who watch the afternoon go by while waiting for their turn at an improvised open-air barbershop. Everyone agrees that after the OLP operations, Mañonguito is doing better. “It’s quiet now; no one comes looking for trouble. We are with our president Nicolás Maduro and our governor, who helps us improve the neighborhood.”

He doesn’t say his name nor wants his picture taken. He has no problem admitting that he participates in illicit activities, though. “We work hand in hand with the revolution. If they want us to lower the price of weapons, they have to compensate us. Drug trafficking you can’t fix. Man is born healthy, but society corrupts him.” He wouldn’t say how much he gets paid.

But not everyone in the village welcomes the presence of the colectivos. Juan Esteban* is a former community leader who chose to walk off from community work after witnessing “strange things”. “I was an enthusiastic activist of the previous government’s crime prevention plan. It was very tough at the beginning, but then we managed to reach children and sow the seed through courses and workshops. It’s all over now. My community is taken by the colectivos. What we have now is fear and distress.”

In Ciudad Caribia, on the outskirts of Caracas and 163 kilometers from Carabobo, the situation is no different after the OLP operation of June 30, 2016.

Ciudad Caribia was one of the first housing projects of the Chávez government. The OLP was carried out by colectivos there, who’ve kept control of the territory ever since.

The official version says that Jordán Pérez Castillo, Ricardo Fabián Cruz Cardona, Joel Pérez, Rodolfo Manrique, Johan Pérez and Anthony López died in confrontations with state security forces. On that list the name of Julio López, Anthony’s brother, was omitted. Five days before the OLP, the men had been identified by members of the colectivo Pérez Bonalde as members of a gang called “Los Sindicalistas”, which allegedly had control over the construction works of Misión Vivienda, the housing program promoted by Hugo Chávez.

“Colectivos are in the construction now. And what do they do? They steal, mistreat, and screw up. It’s as if they had more power than the government. They have more guns than the police, they carry a radio and a gun,” said an area man. Since the paramilitary group took over the construction union, all the projects have been paralyzed. “The government sends (the materials), but they don’t do anything,” he added. Several residents claimed that everything was resold in the black market.

The OLP didn’t reduce crime in Ciudad Caribia. Shortly after the massacre, they stole sound equipment from the chapel located on Terraza B. Burglaries and housebreakings increased, vaccines came at a cost and the activities of the residents in Misión Vivienda were controlled.

The families of the seven victims of the operation who are still living in the urbanization prefer to lock themselves up at night. “Nobody goes out because they (the colectivos) are always around,” said one of them. She’s cut relations with her neighbors out of fear, and doesn’t feel free to talk about anything on the streets of Ciudad Caribia. She arrived there after having lived for years in the precarious shanties of Tacagua, west of Caracas, where a downpour left her injured and homeless. Despite all the hardships, she says she was happier there. “I would have preferred to be left there in my neighborhood than to live this.”

During the OLP of June 30 in Ciudada Caribia, the colectivos also prompted the arrest of US citizen and Mormon missionary Joshua Anthony Holt. He and his wife Tamara Belén Caleño Candelo, born in Ecuador and nationalized Venezuelan, were waiting for some personal documents that would allow her to leave the country and settle in the United States. But the OLP undermined their American dream. Holt, 25 years old, had been less than a month in Venezuela when he was arrested. He had just married Caleño Candelo, 26, who worked as a receptionist at the Centro de Diagnóstico Integral in Ciudad Caribia, an institution belonging to the health network created by the chavismo with Cuban medical practitioners.

Both were charged with illegal possession of weapons of war. State security forces say they found an AK-47 rifle, a MK2 grenade and ammunition inside their home, located in Tower 12, Terrace A of the building complex. However, neighbors insist that everything was “sown”: the product of a trap set by colectivos and security forces. Their lawyers claim that the couple has been denied their right to defense and due process, because the preliminary hearing they had to attend in August 2015 never took place. There is no accusation against Holt and mediation efforts by the United States have not worked.

Donald Trump’s administration has referred to the event in several opportunities, and has requested the immediate release of Holt for “humanitarian reasons” after his family claimed that he needs medical attention. The case even made it to one of the executive orders with which the Treasury Office sanctioned Venezuelan officials, stressing the concerns of the Trump administration.

Joshua Holt and his wife.

Photo: RR SS

In Venezuela, Holt’s attorneys have reported that he has been subjected to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment in the SEBIN cells. After his arrest, instead of being brought within 48 hours before a judge, as established by law, he was taken to court a week later. According to unofficial versions, the reason for the delay is that officers were trying to extort him. As he did not pay for his freedom, he was imprisoned and the government, through the Minister of Internal Affairs and Justice of that time, Gustavo González López, spread the image of Holt as an American spy.

González López, current director of SEBIN, said that Holt’s apartment was a repository for weapons of war and explosives. He claimed that it was the “niche” of the paramilitary criminal gang operating in the area, and that both him and Caleño Candelo were passionate about guns and had had a strange online relationship that ended in marriage. That way, the member of the executive cabinet accepted the finger pointing made by the groups that accused Joshua Holt, who is still in a SEBIN prison.

In areas like El Cementerio, El Valle, Coche and la Cota 905, where the OLP has been more aggressive and persistent, residents say that the intention of these operations is giving the colectivos the control over social and political life, as well as the criminal economy operating in those territories. These areas are of the few in Caracas where the presence of these paramilitary groups is almost non-existent. Two are already operating in El Valle, with little strength. They monitor and intimidate the residents to prevent them from going out to demonstrate against the government of Nicolás Maduro.

Stages and motives

Although the OLP was created two years ago as a security plan, its objectives and goals have not been formally disclosed and a manual of procedures regulating its actions did not exist until January 2017. An administrative officer of the PNB said that the OLP “is valid until a new plan is announced.”

The Public Ministry’s Report of Proceedings Related to the OLP defines this security plan as “Militarized police procedures carried out by different security bodies, including the National Bolivarian Police Force (CPNB) the Bolivarian National Guard (GNB); the Bureau for Scientific, Criminal, and Forensic Investigations (CICPC); the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) and some state and municipal police.”

That’s how it began on July 13, 2015, apparently in response to a series of acts of violence that had been registered in Cota 905 (southwest of Caracas), Barlovento and Valles del Tuy, three sectors that had been transformed in 2013 into Zonas de Paz (Peace Zones) by José Vicente Rangel Ávalos, then Vice Minister of Public Safety. The territories have been left in the hands of criminal gangs.

An inspector from CICPC who participated in that first OLP in Cota 905 recounted his experience without remorse. “They told me about the procedure. And I went up there because I had already had clashes with those gangs and lost some comrades. Yes, I participated, and well yes, I killed some, but the truth is that the leaders of the bands were not there. ‘El Koki’ –alias of Carlos Luis Revete, one of the most wanted criminals in Venezuela– had left the night before because he was tipped off by people of the government, and left with his closest” he explained with disenchantment.

After that first experience, the inspector understood that the aim of the OLP was not precisely to reduce crime, nor to guarantee the safety of citizens. “It’s a circus, a circus … and we are the clowns. It’s pure propaganda.”

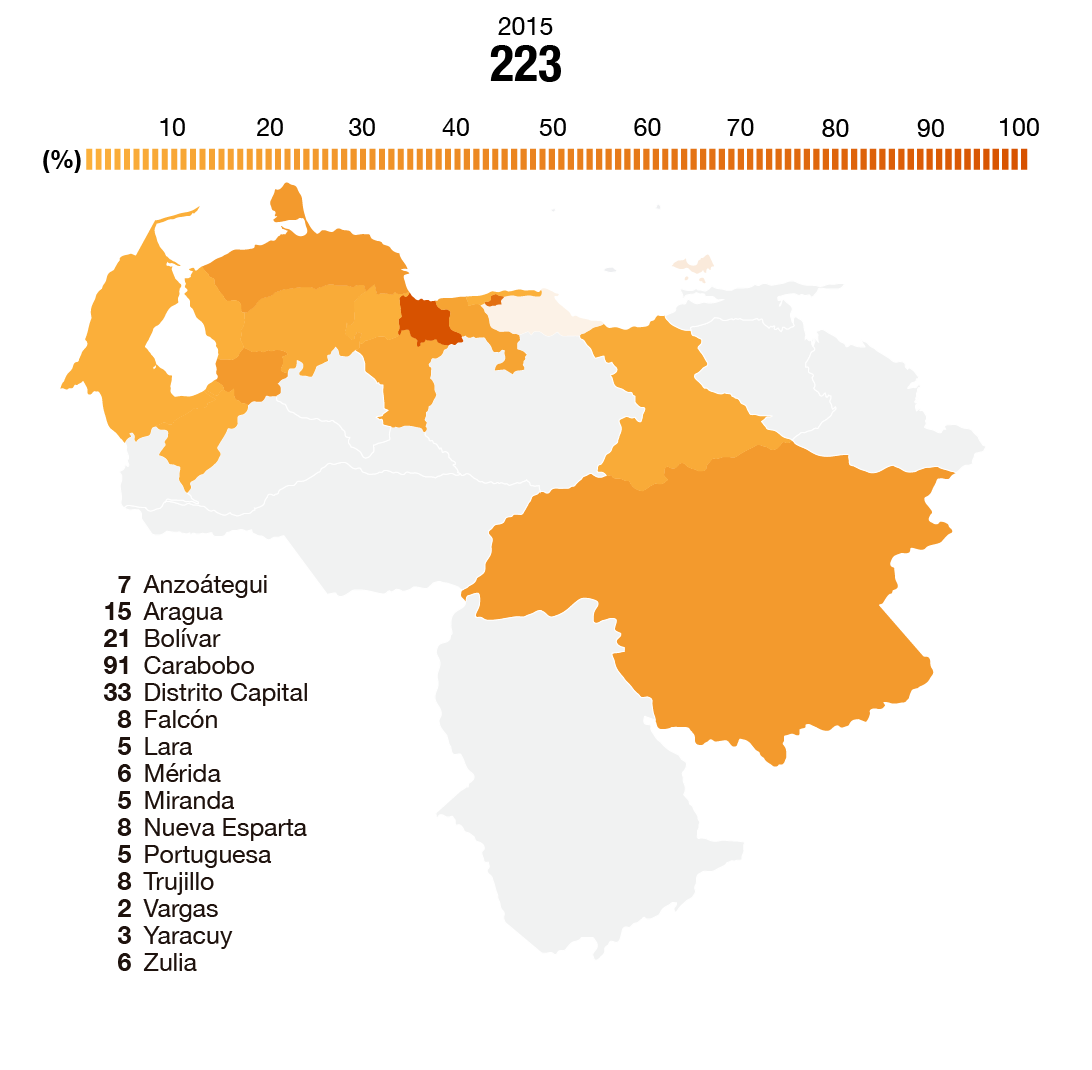

The OLP made its first appearance five months before the elections for the National Assembly (AN) on December 2015. Some analysts say it was only a government measure to try to recover its lost popularity. And although the surveys of the first months showed an apparent success, the result of the electoral process ruined the hopes of the ruling party.

Keymer Avila, a researcher at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV), who has been studying the OLP since its beginnings, explained the propagandistic use of its operations: “They wanted to give the impression that something was being done with the crime problem, hence the importance of the media coverage and the propaganda around these operations. The highest amount of news were published in August 2015 and disappeared after the December elections. This could be the basis to affirm that at least in 2015, the OLP was mainly a campaign strategy that turned out to be ineffective for its political purposes, because those elections were won by the opposition.”

In those days it was frequent to see President Maduro on national television with his ministers, governors and candidates for the AN. The leaders of the districts that had the greater amount of OLP victims stood out: Francisco Ameliach, governor of Carabobo; Tareck El Aissami, governor of Aragua and Elías Jaua, then Protector of Miranda and aspiring to a seat in that state.

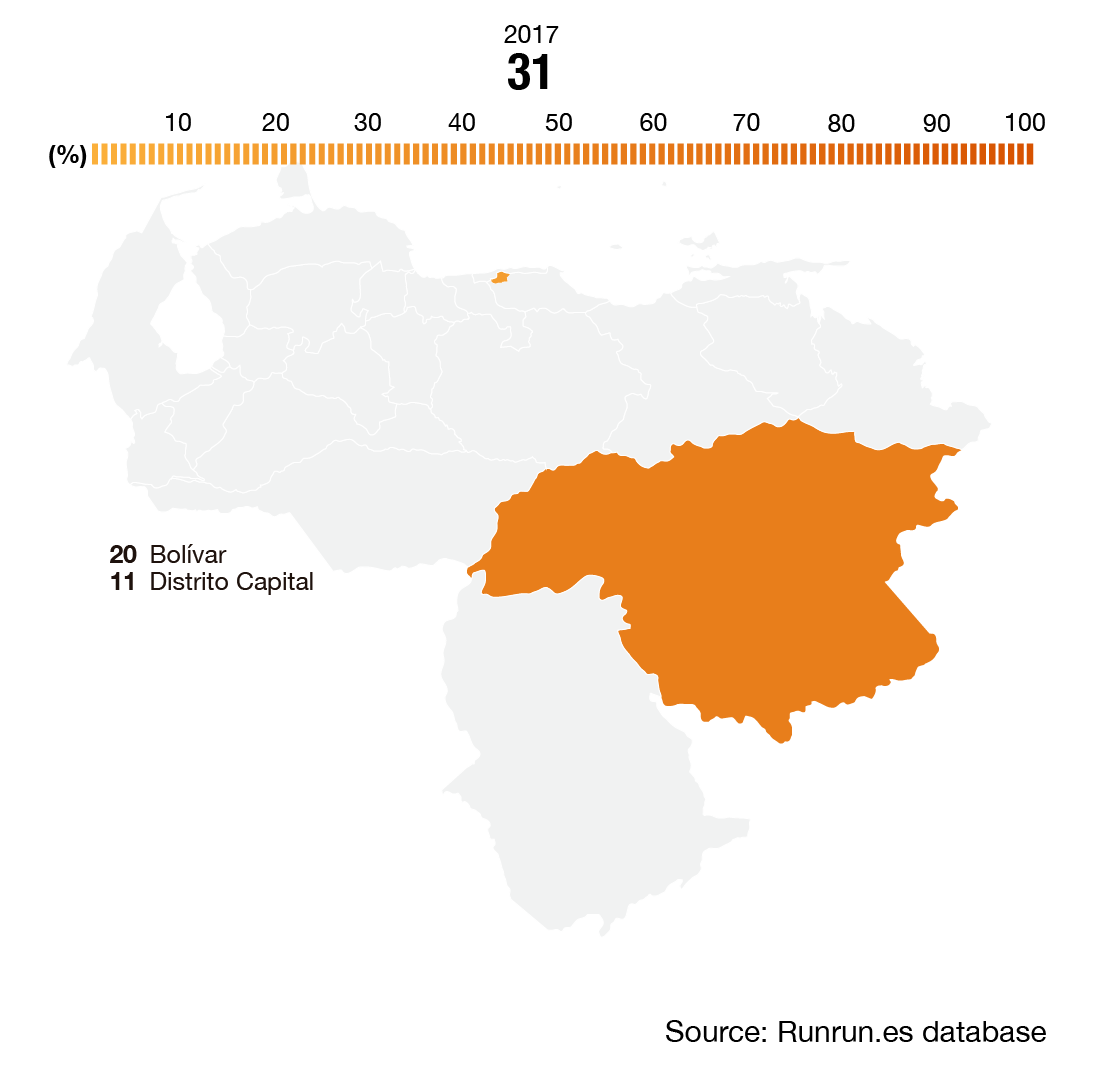

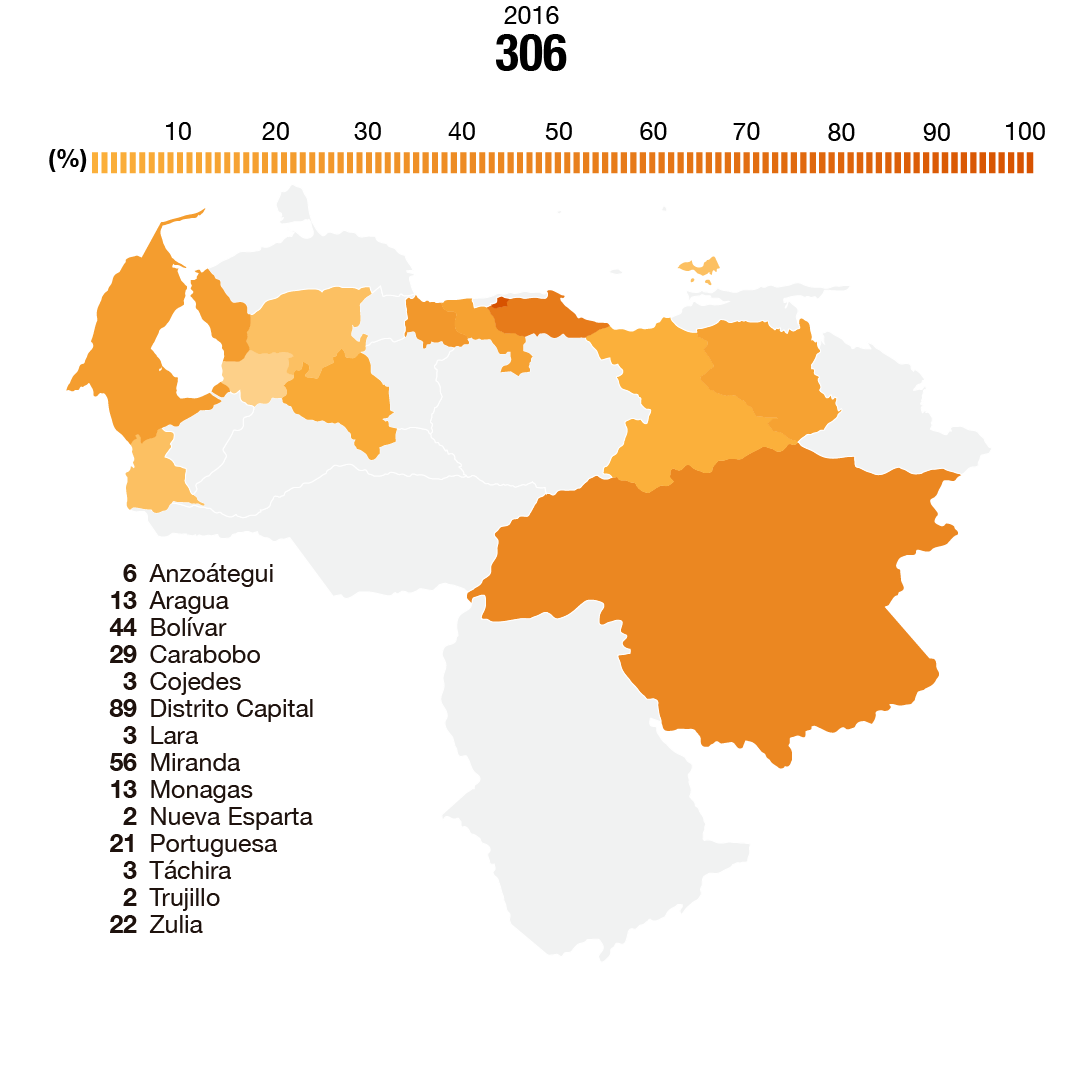

Deaths by state

Number of victims per each since the emergence of the OLP

Jaua was also appointed head of the OLP Presidential Command, and activated several operations carried out in Valles del Tuy and Barlovento, where he is known as “El Gran Cacao”. The nickname relates to his links with the production, marketing and export of cacao, whose cost is priced in dollars, and is extremely attractive for the armed gangs in the area.

While for President Nicolás Maduro the OLP was “the instrument for the construction of a new system of security and peace with a deep socialist orientation and integrated by popular and military power”, Transparency Venezuela argued in its bulletin of October 27, 2015, that the OLP “is more a political strategy than a program to combat insecurity, given that it has no set of principles, conceptualizations, geographical delimitation or approaches aimed at solving the problem”.

The announcement of the second stage of the OLP took everyone by surprise. Like the first one, it became known from an early morning seizure of areas of El Valle, Cota 905 and El Cementerio on May 10, 2016. The procedure left nine people dead. That same day, when offering an account of the events, the head of the MRIJP, General Gustavo González López (now director of SEBIN), reported that it was the OLP-NF (New Phase) and explained that from then on it would be a “selective” operation.

This new element, which consisted in the specific and precise search of alleged criminals, was refined with the use of “social intelligence”: an information mechanism through which communities, residents and representatives of the government’s political structures would provide details to identify and locate the alleged “paramilitaries”. This was the explanation extended by President Maduro and Deputy Minister of Public Safety, Ketherine Harrington in public statements.

The use of “social intelligence” ended in the murder of some informants. On the night of June 27, 2016, Elizabeth Margarita Aguilera Vegas was cornered, shot and burned as she walked down the main street of the San Miguel de la Cota neighborhood in 905. She was allegedly attacked by criminals who believed she had reported them before the authorities. The 43-year-old woman was the head of the Bolívar-Chávez Battle Unit (UBCH) that operates in the Sucre District School.

Photos on cell phones and tablets, names written on slips of paper, prostitutes and hooded witnesses were used by law enforcement to identify the people they were looking for during the OLP. The arrest of Danny, Eliecer and Freddy, victims of the Barlovento massacre, was not random. They went to Eliecer’s house looking for him on the claim that he was the garitero of the town’s gang. Danny was taken from a public transport unit, his identity checked, and detained despite having no search requests or police records.

After spending months without finding an explanation for this massacre, the possible motives behind the killing were the common comment among the residents of Capaya and the neighboring town, El Café. “That massacre occurred because they were looking for the killers of Miguel. He was the husband of a niece of the vice president Aristóbulo Istúriz and was the escort of a goat (an influential person). He was from El Café, but always bet on horses in Capaya. They killed him there to take the money he had collected and steal a very large motorcycle he had,” Juan Carlos said.

He was referring to Miguel Ángel Mijares Acevedo, 40, killed on June 5, 2016 on an alleged robbery. The crime was committed by members of a criminal gang of Capaya, who ambushed both Mijares and his brother. They made them run from the horses’ betting stand to the entrance of town. They were surrounded by 15 armed men who shot them. Miguel died, but his brother survived. The motorbike was found, half dismantled, at the house of two of the alleged murderers.

Miguel Mijares, husband of a niece of former vice president Aristóbulo Istúriz, was murdered in Capaya and the “pursuit of justice” for his murder is behind the Barlovento massacre.

This crime motivated several OLPs, with the support of Army officials who stayed in Barlovento and settled in El Café. “We don’t know why they stayed here,” said the CONAS officer. The operations to capture the members of the gang that killed Mijares lasted until the beginning of June 2017, when it was rumored in town that two other members of the group had “fallen”. “But the leader is still missing,” Juan Carlos said.

After searching for explanations, the relatives of the victims of the massacre agree that it could have been a revenge for the murder of Mijares, occurred four months earlier. Although there is no direct connection between the Mijares crime and the victims of the massacre, there are elements that could have made them targets of the military. Freddy Hernández was a motorcycle rider and the best motorcycle mechanic around; Eliecer Yustaris was a military serviceman, and when he was arrested, he was accused of being a supplier of weapons to the gangs in the area. Danny Acevedo was a farmer but his favorite hobby was betting on horses, and had frequented the same equestrian center as Mijares.

Days after the discovery of the bodies, a mass was held for the victims in the town of Caucagua. José Vicente Rangel Ávalos, who by then was serving in a position at the Vice Presidency of the Republic, attended the Eucharist. “Those are the things you can’t make sense of. If that Mr. Ávalos met with the bands for arranging the Peace Zones and knows who their members are, then why do they come and kill the innocents? Why don’t they go after the gangs?” wondered a resident from Rio Chico in Barlovento who knows the area and its criminal structures well.

José Vicente Rangel Ávalos made pacts with criminal groups and promoted the creation of peace zones in Barlovento and Valles del Tuy. The gangs were strengthened and those are now the most violent areas in the country

Photo: Screenshot of a video broadcast by Televen

At least other massive PLOs with more than a dozen deaths were completed in the Barlovento area in the first half of 2016, after military men were victims of kidnappings and homicides. According to the CONAS officer, the operations were only carried out under the orders of President Maduro and the commander of the GNB. However, the lack of control and supervision over the actions ended in cases such as the Barlovento massacre.

The 2016 Management Report of the Ombudsman’s Office gives an account of this. The offices of the organization throughout the country, which promote human rights and monitor their situation, were never called in to the OLPs because “some were carried out unexpectedly; police agencies considered that the participation of this institution was not relevant, or were notified after the operation was carried out, only to verify if any type of violation of human rights had been committed.” The document states that the Ombudsman’s Office only participated in 26 OLPs registered in the national territory during 2015, according to official data.

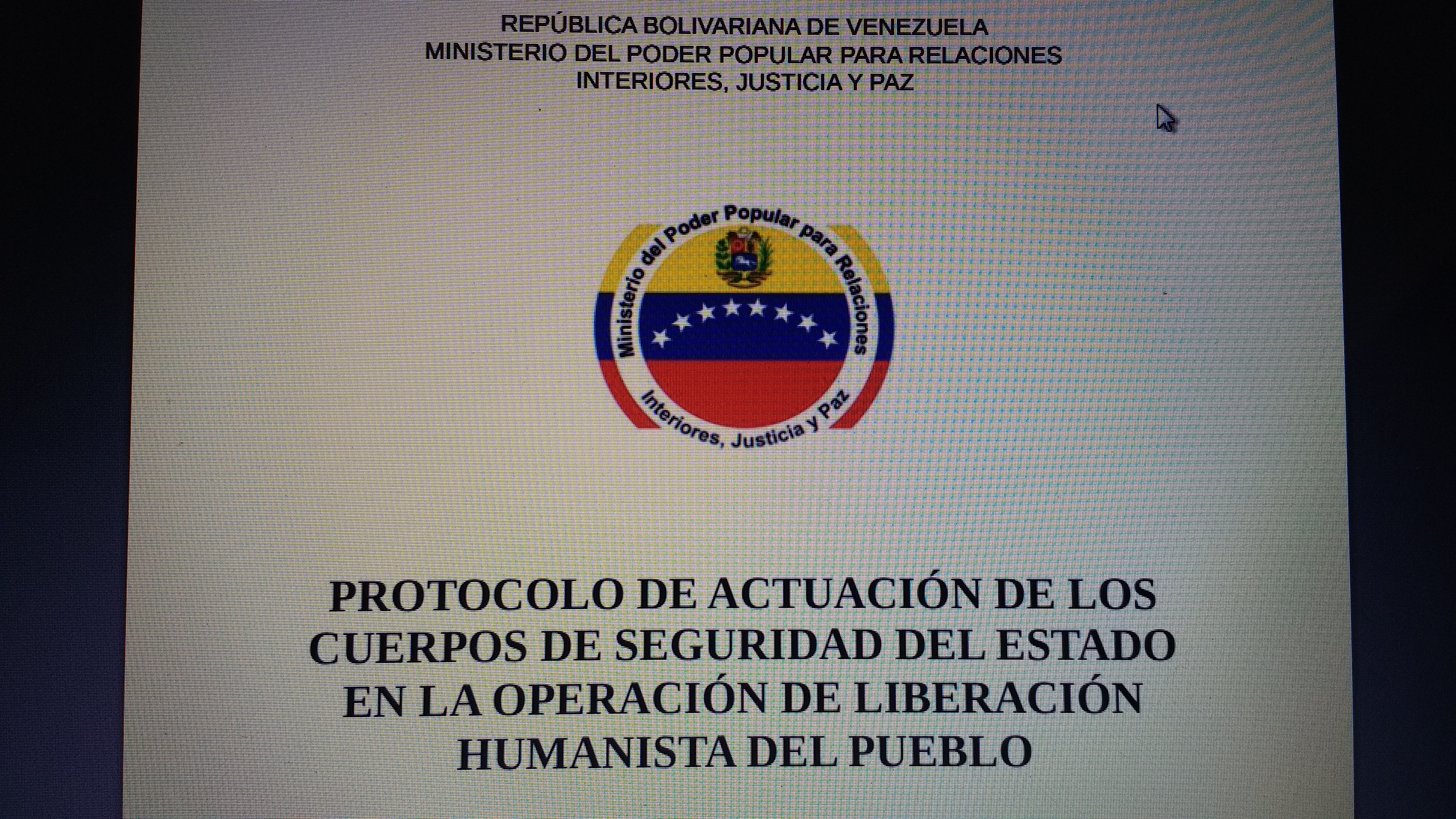

The third stage of the OLP began in January 2017. This time President Nicolás Maduro made an addition to the original name. Now it would be OLHP, the “H” standing for “humanists” and having to do with the respect for human rights. It was on the occasion of this re-launch when an official document defining the OLHP was drawn up.

The Protocol of Action of the State Security Bodies in the Operation for the Humanist Liberation of the People (OLHP), to which Runrun.es had access, says that the action of the OLP covers the urbanizations of Misión Vivienda, and states: “The Ministry of the Popular Power for Internal Affairs, Justice and Peace, is the main responsible for the OLHP, together with the Minister of the People’s Power for Defense. For this reason, this protocol is established as a tool to guide police action through the Operation for the Humanist Liberation of the People (OLHP)”.

President Maduro launched the OLHP “with a new superior vision in quality and effectiveness in human rights achievements,” according to the official document.

Document about the protocol of action of the OLP security bodies, prepared by the Ministry of Interior, Justice and Peace in January 2017, a year and a half after the launch of the OLP

Chapter II includes a statement that could be considered an official definition of the OLHP. “It is the System planned and articulated by the Ministry of the Popular Power for Internal Affairs, Justice and Peace, together with the Operational Strategic Command of the Bolivarian National Armed Forces, to generate actions that allow the coordination of the Citizen Security Organizations, the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN), state and municipal police bodies and the FANB, for the liberation of areas taken over by the organized crime, in order to eradicate criminal and paramilitary activities, guaranteeing the protection of the people by means of the execution of plans concerning citizen security against any internal threat to the effective exercise of the individual liberties and the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights in the comprehensive development of the Nation”.

The fear remains

“If I hear the expression OLP I pee myself.” This is Maria*, a resident of Ciudad Caribia, who recalled the terror she felt the morning of June 30, 2016, when officers of the PNB, SEBIN and the colectivos, broke into several apartments and left a balance of seven dead and 10 arrested.

“I’m nervous because I think of my 17-year-old son, because they can take him like they did to my other boy, you know?” María said. Anxiety spreads among the inhabitants of Cota 905, El Cementerio, El Valle, Ciudad Socialista Hugo Chávez (in Barlovento), Loma Linda (in Callao), San Vicente (in Aragua) and Boquerón (in Carabobo) when they are mentioned the OLP.

Ciudad Socialista, an urbanization of Misión Vivienda in the municipality of Acevedo, is one of the most dangerous places in the area. “It’s like a prison without bars,” the CONAS officer said inside his office, located 500 meters from the residences. He admitted that he visits them frequently to do OLPs or proceedings against kidnappers.

In Ciudad Socialista Hugo Chávez, Barlovento, there was an OLP raid almost every week.

The urbanization is reached by public transport or walking the 300 meters that separate it from the main road where Chocolatera Orion, one of the emblematic companies of the government cocoa project, is located. The SEBIN headquarters in the region are about 200 meters before the entrance, and 100 meters ahead there’s an office of the GNB. With so many security forces guarding the entrance of Ciudad Socialista, the recurrent need of the OLP is paradoxical.

In Caucagua and its surroundings, people agreed that Ciudad Socialista was a constant target of the OLP. “The OLP went in every day,” said Juan Carlos*, a driver who provides services in the area. However, the residents walking on the sidewalks of the buildings on any given day exchange glances when asked about the OLP. They remain silent or pretend not to know. “Noooo, I’ve never seen such thing here,” said one of the few people who dared to answer the questions of the unknown visitor. “There’s no OLP here, right?” he asked his companion looking to confirm his answer.

Another resident indicated that it was better to make those questions to the building manager (an informal authority figure who exercises control over the residence). Each of the buildings that make up urbanization has a boss who decides who speaks and what is spoken. Anyone who does not comply with that rule receives a punishment, explained Juan Carlos*, who only spoke when leaving the place.

“We had never seen such level of fear before, or the consequences of seeking justice out of fear”, says Liliana Ortega, who for 27 years has given assistance to relatives of victims of executions and other human rights violations. “The fear that victims have of being identified as complainants has no comparison to anything I’ve seen in the past.”

In Cota 905 the men ran, the women and children locked themselves in the houses, and did not dare even to look out the window when the OLP arrived. “We know when they come, because we can see them from here,” said Rosa*, pointing to El Helicoide, where an office of the PNB works. “Those people are scary. Even the women are bad. They insult you and beat you. We call them ‘those in black’, because they come with all those black clothes and their faces covered.”

Ortega claims that there was a criminalization of families and complaints of abuse, threats of sexual violence and harassment were common when the operations were carried out. Based on the reports of those affected, the NGO COFAVIC also detected “internal forced displacements. Families that decided to move and leave their houses and their belongings to save the rest of their members.”

In Merecure, Marizapa, El Delirio and other Barlovento towns, dozens of homes were abandoned and put on sale at prices below market value after the OLP. In Valles del Tuy the displacements have been massive, especially in Santa Lucia. “People first left because of the pressures of the unions and conflicts between gangs. But later, when the OLP arrived, there were also displacements and we didn’t understand why. It was because the OLP killed gang members and gave control to union members or to some other gang linked to people in the government,” said a resident of Santa Teresa. The visit of the then Minister of Public Safety José Vicente Rangel Ávalos to Valles del Tuy was taken by the residents as a sign that an OLP would come.

Balaclavas and death masks were part of the OLP’s terror-inducing appearance.

Photo (file): Courtesy of Carlos Ramírez

In Merecure, Marizapa, El Delirio and other Barlovento towns, dozens of homes were abandoned and put on sale at prices below market value after the OLP. In Valles del Tuy the displacements have been massive, especially in Santa Lucia. “People first left because of the pressures of the unions and conflicts between gangs. But later, when the OLP arrived, there were also displacements and we didn’t understand why. It was because the OLP killed gang members and gave control to union members or to some other gang linked to people in the government,” said a resident of Santa Teresa. The visit of the then Minister of Public Safety José Vicente Rangel Ávalos to Valles del Tuy was taken by the residents as a sign that an OLP would come.

“In San Vicente (Aragua state) you live in terror. You can’t do anything without the authorization of the thugs. No light bulb is removed, no wall is painted without their approval. You can’t paint your walls the color you want, for example, and you have to put a light bulb on your door or remove it because they say so. If you don’t follow their rules, they threaten to take your house away and give you 24 hours to leave the neighborhood. And if you don’t go away, they kill you. That happened to the owner of a bikes workshop. They told him not to receive the police anymore. He ignored them and they shot him right there in front of his son,” recalls Nidia*. Despite the deaths, the criminals of San Vicente did not allow the advance of the OLP. Or perhaps the protection of someone with power prevented it.

Some national and international NGOs, state institutions and foreign governments have questioned and warned about the dangers of the OLP, considering them procedures that violate human rights.

In a report published three months after the OLP, Transparency Venezuela said: “It is urgent to stop or redirect this operation that violates human rights principles. It should be a public oriented policy that covers the problem focusing on prevention, disarmament and police control.”

On November 1, 2016, during the second Universal Periodic Review on Human Rights at the UN headquarters in Geneva, the government of Canada recommended that Venezuela eliminate the OLP. ■

Selection of Victims

* The names of the victims were changed for their safety.

* Reports and official documents of the Public Ministry were removed from the website of the institution after the dismissal of Attorney General Luisa Ortega Díaz. Runrun.es has copies