Executions, theft and impunity

Relatives of the OLP victims interviewed for this investigation stated that their family members were executed by security forces. During the operations they were also subjected to mistreatment and theft by security forces. None have had access to the autopsies of the murdered people. Impunity is the rule.

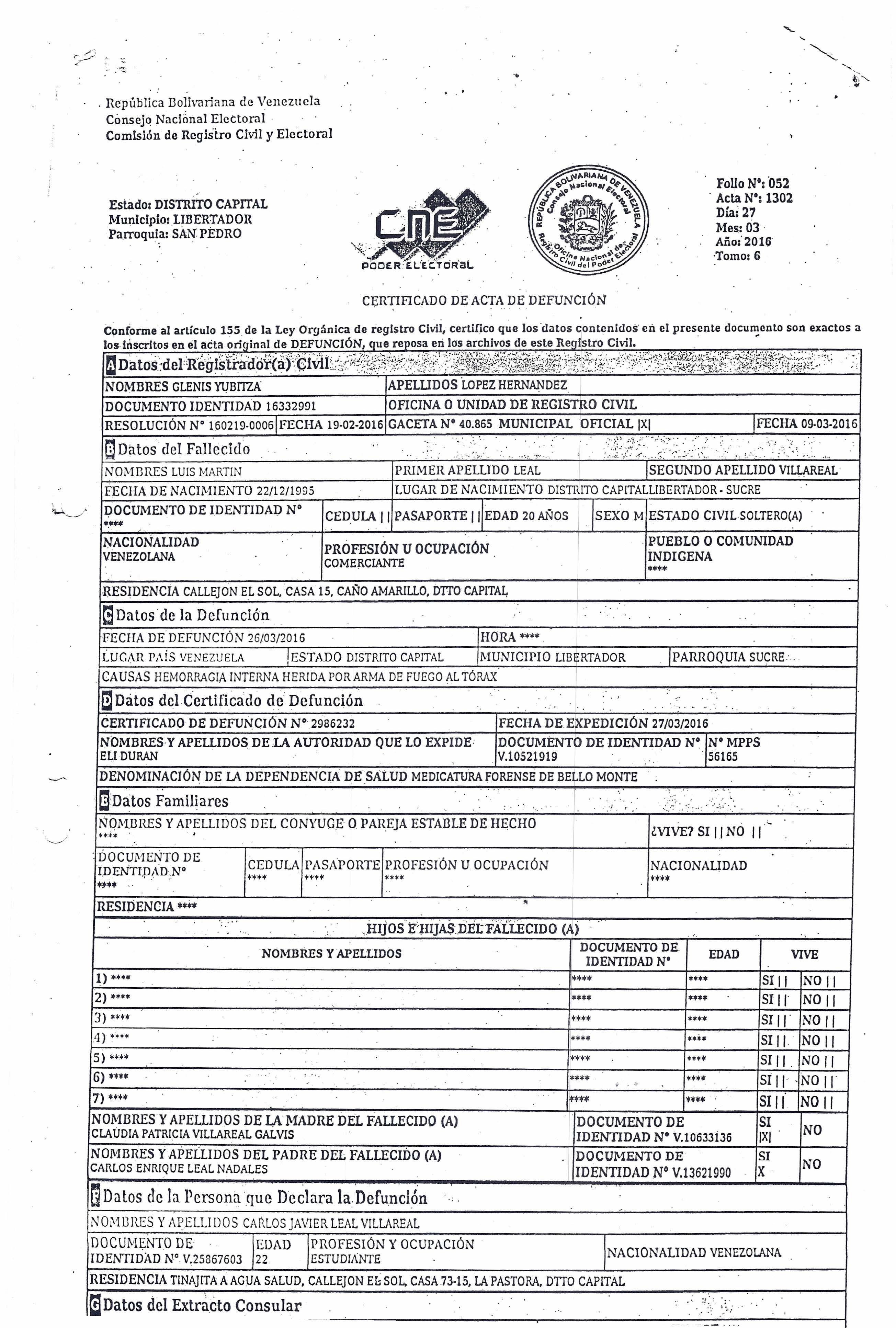

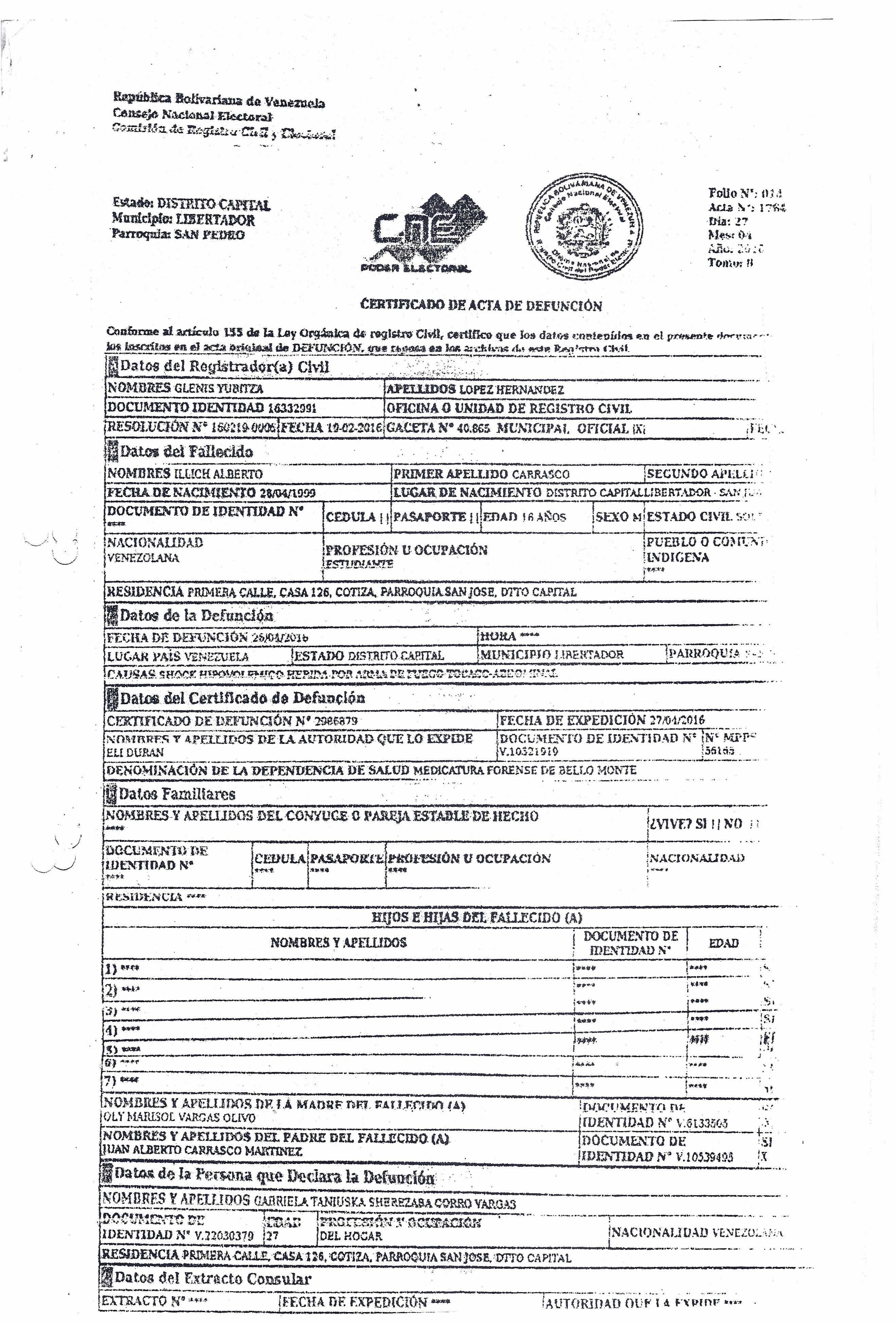

Julia’s son had four bullet wounds when she found him dead at the Miguel Pérez Carreño hospital: one on the head, one on the shoulder and two on the chest. The death certificate that was handed over to her at the Bello Monte morgue indicated as causes of death “abdominal hemorrhage and skull fracture due to gunshot wound.” On March 9, 2017, three other people died at the hands of FAES in the same sector. The neighborhood children remember the event accurately: “The police came firing shots. They used silencers,” said a 10-year-old boy who played with marbles on the dirt court.

Most of the homicides committed during the OLPs have been described by the witnesses as summary executions. Authorities, however, consider these events as cases of resistance to authority or clashes between police and criminals. COFAVIC, an NGO dedicated to investigate and register cases of executions since 1989, when El Caracazo occurred –a social outbreak that left hundreds dead– accounted for an increase from 1,396 to 2,197 in complaints from family members of victims in 2015 and 2016. This represents an increase of 59.6 percent in one year.

Ratio between the number of civilians and the number of policemen killed in OLP

According to witnesses, may of these executions have taken place inside the houses, where officers usually simulate confrontations and prepare a crime scene that will exonerate them from blame. The bodies are wrapped in sheets and taken away without the scientific police doing their job. “The crime scene and the corpse are key in the police investigation to solve a homicide. They are crucial for determining whether it was a confrontation or an execution and identifying the responsibilities,” said Commissioner Luis Godoy, former head of homicide investigations of the Judicial Police.

The murders of brothers Julio and Anthony López Quijada occurred inside one of the apartments of Terrace B in Ciudad Caribia. They lived with their mother, whom the soldiers pointed with a gun to force her out and away from her home. When she went back in, all she was able to see was the pool of blood that had been left in the middle of the room before the department was quickly closed with a security seal for several days. They covered her children with blankets and put them in the back of a pickup truck that ran through the entire complex collecting the bodies of the rest of the dead.

Ciudad Caribia is a building complex, west of Caracas, built by the government for low-income families. The armed groups commanded an OLP that was carried out in the urban environment, where seven men who lived there were executed

Witnesses claim that after killing the López Quijada brothers, officers shot at the door and the wall leading to the corridor of the building to fake a shootout between villains and avengers. According to the neighbors, none of the boys had guns, but the police reports on the case indicated that Julio carried a 16-gauge shotgun and that Anthony had fired a .38-caliber revolver. The people who witnessed the incident agree that the weapons were planted.

On other occasions, the victims are taken from their homes, without major injuries, and their bodies appear later in hospitals or in the morgues with gunshots.

Rodolfo Manrique lived in building 17, very close to the López Quijada family. They took him from his house almost asleep at 5 in the morning that same day. “I’m not afraid of justice because I haven’t done anything,” he had said days before he died, when the colectivos singled him out as one of the members of the gang “Los Sindicalistas” and threatened him with a police raid. All those killed during that OLP had received the same warning.

Shortly before noon, Manrique’s family found him in the morgue of Bello Monte with a shot in the chest. The police report said that he had resisted authority and had a 380-caliber pistol with him.

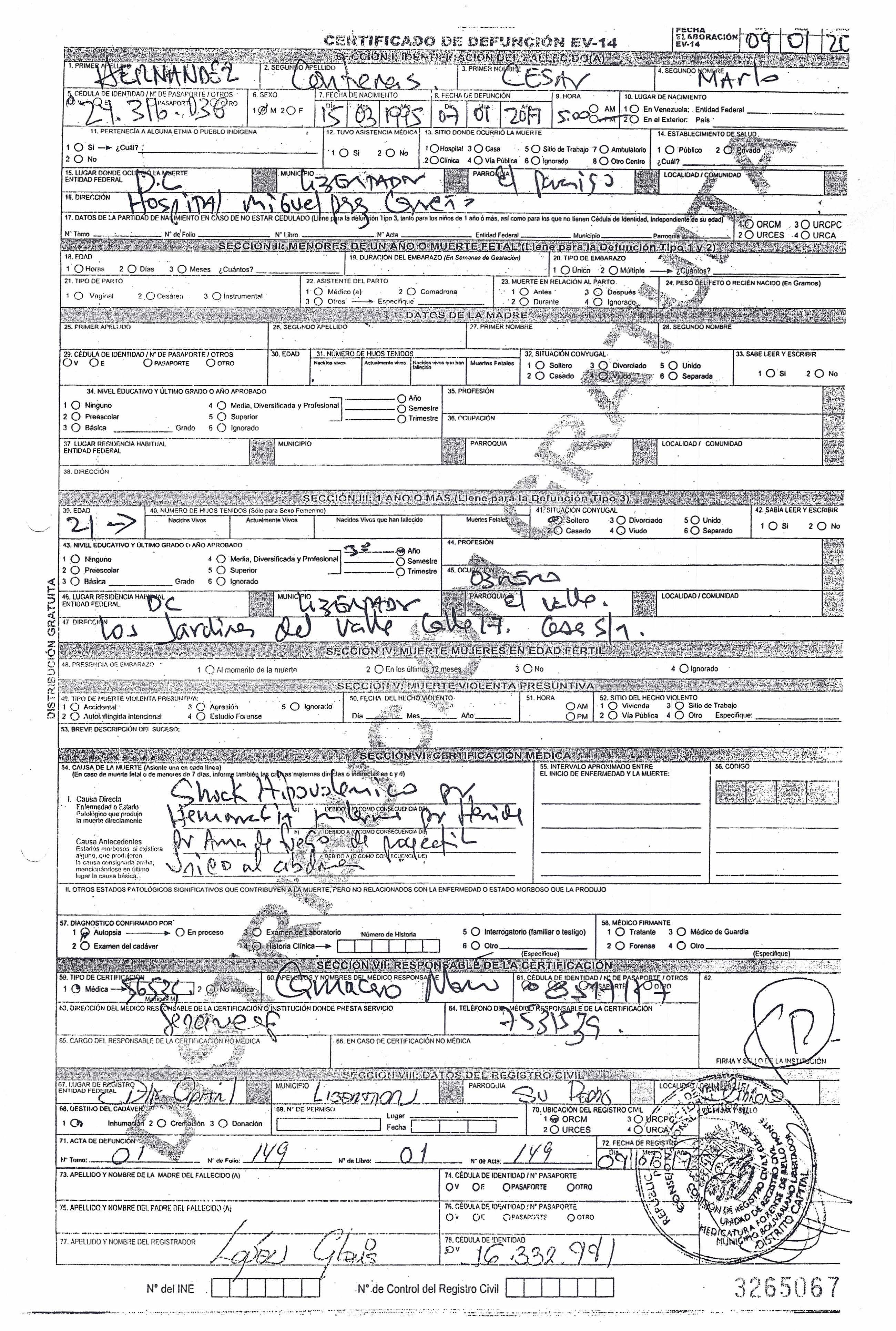

Ángel Carrasquero, son of Luis Ángel Carrasquero, was taken from his house in Los Jardines de El Valle. “My son was caught at about 7:30 in the morning, when he was going to work. They took him to an alley and killed him there. I tried to go but the police wouldn’t let me. After a while four or five shots were fired and I worried, I tried to go to my son again and they didn’t let me”. He had two bullet wounds when Luis Ángel found him at hospital Periférico de Coche: one in the neck and one in the mouth. Carrasquero thinks the murder of his son during the OLP of March 10, 2017, was a vendetta by an undercover police officer because the victim had refused to pay a bribe.

Judicial inquiries involving the OLP face several obstacles. Liliana Ortega, director of COFAVIC, identified some. “The line of investigation of the Public Ministry never varies; it focuses on demonstrating the death of the person and then they check if there was a confrontation. It is not investigated if it was an extrajudicial execution.”

“They say they are the OLP, but the truth is they are murderers,” said an outraged resident of Loma Linda, an impoverished area of El Callao, in Bolivar state. On June 14, the hooded army arrived looking for the house of the Villegas Hurtado family, to avenge an incident that had occurred a few days earlier at the funeral of a neighbor who was killed by security forces. “We were surrounded by the military. Some of them went up to the roof, fired some shots and threatened to throw tear gas if we defended the chamos (kids). They took Alfredo out of the shower and shot him twice: once on the chest and once on the belly, and then they hit him badly with the mandarria. They put a wood plank on him and struck it with the hammer. The other boy, who was his friend, was killed in the room where he was watching television. They shot him and disfigured his face with blows,” said the witness, who asked that his identity be kept secret.

The men removed the bodies and threw them in the back of a truck labeled with the CICPC seal. They also loaded two air conditioners that had been taken from the victims’ house. But the version that was published in the press was different. It said that the miner Alfredo Villegas Hurtado and his friend had died after hiding in a house and confronting the security forces. Both were called by an alias and associated with the gang led by “El Ángelo”, pran of mining in El Callao.

Control of the mines, and the gold trade are related to the murders in El Callao and Tumeremo (Bolivar State) in the context of the OLP

After the events, the family Villegas Hurtado decided to remove their youngest children from the neighborhood. Other residents of Loma Linda did the same because they fear that the boys might be killed any time without reason.

“This situation not only affects the direct victim, whom is denied of the right to live. We are talking about a blow to the whole family: mothers are tortured and children witness how they kill their own. Even if the OLP is selective, the trauma is collective. And while they’re looking for those they want, the rest of the people live in a state of terror,” said Ronnie Boquier, lawyer at COFAVIC.

“They subdued him, tied him up, and put a hood on him”

Since the launching of the OLP in July 2015, the death of civilians at the hands of state forces multiplied. Commissioner Elísio Guzmán, director of the Miranda State Police (intervened by the Government after the protests of April 2017) shows some figures from the region. According to his statistics, before July 2015 an average of 18 civilian deaths at the hands of security forces were registered each month. In January 2016, this figure had risen to 90 deaths per month due to confrontation, six months after the government had implemented the Operation to Liberate and Protect the People. “Most of these cases are executions. You can’t give people a license to kill,” said the officer, adding that the police force he runs is not invited to participate in the OLP, because the governor of the state is a member of the opposition.

The son of Martha, the son of Asdrúbal, the son of Juanita*, the son of Julián*, the son of Alex, the brother of Javier*, the children of Clara*, the husband of Kimberly, the cousin of Mariana*, the son of the Acevedo-Vahamonde couple, and all the relatives of the people interviewed for this investigation were victims of executions during OLP proceedings, according to their testimonies.

When the police not only kill, they also steal

The OLPs have served as an excuse for officials to come out with their hands full. The victims of these operations have claimed that, during the illegal raids, the members of the state security bodies take their belongings. They steal electronic equipment, cash, vehicles and even food. The arrival of the uniformed seems to leave, more often than not, a trail of devastation.

Since the first OLP in July 2015, the destruction of the homes and assets of the OLP victims is constant

Photos (file): Runrun.es

A CONAS officer with wide experience in the OLP cynically admitted that sometimes there are excesses, but justified the action and application of those improvised lootings “when households are involved in crime.” He said that if the houses have been used to hide kidnapped people, store stolen merchandise or as a den of criminals, then police officers have a “license” to take a booty and destroy the place, if necessary. “We always do that with the cambuchas” (makeshift huts in wooded areas, where criminal groups keep the kidnapped) he said.

The list of stolen goods taken from Alex Yorman Vegas’ house –father of a teenager killed during a OLP in El Valle, Caracas– were as personal as his watch, shirts and even the new shoes that he had bought his son for the Fiestas Decembrinas. “They took the girl’s tablet, the DS, the computer speaker, the mouse, flour, sugar… My cologne, my wife’s cologne, my daughter’s… It happened on March 10, 2017,” he recalled. That day his boy was murdered in their living room.

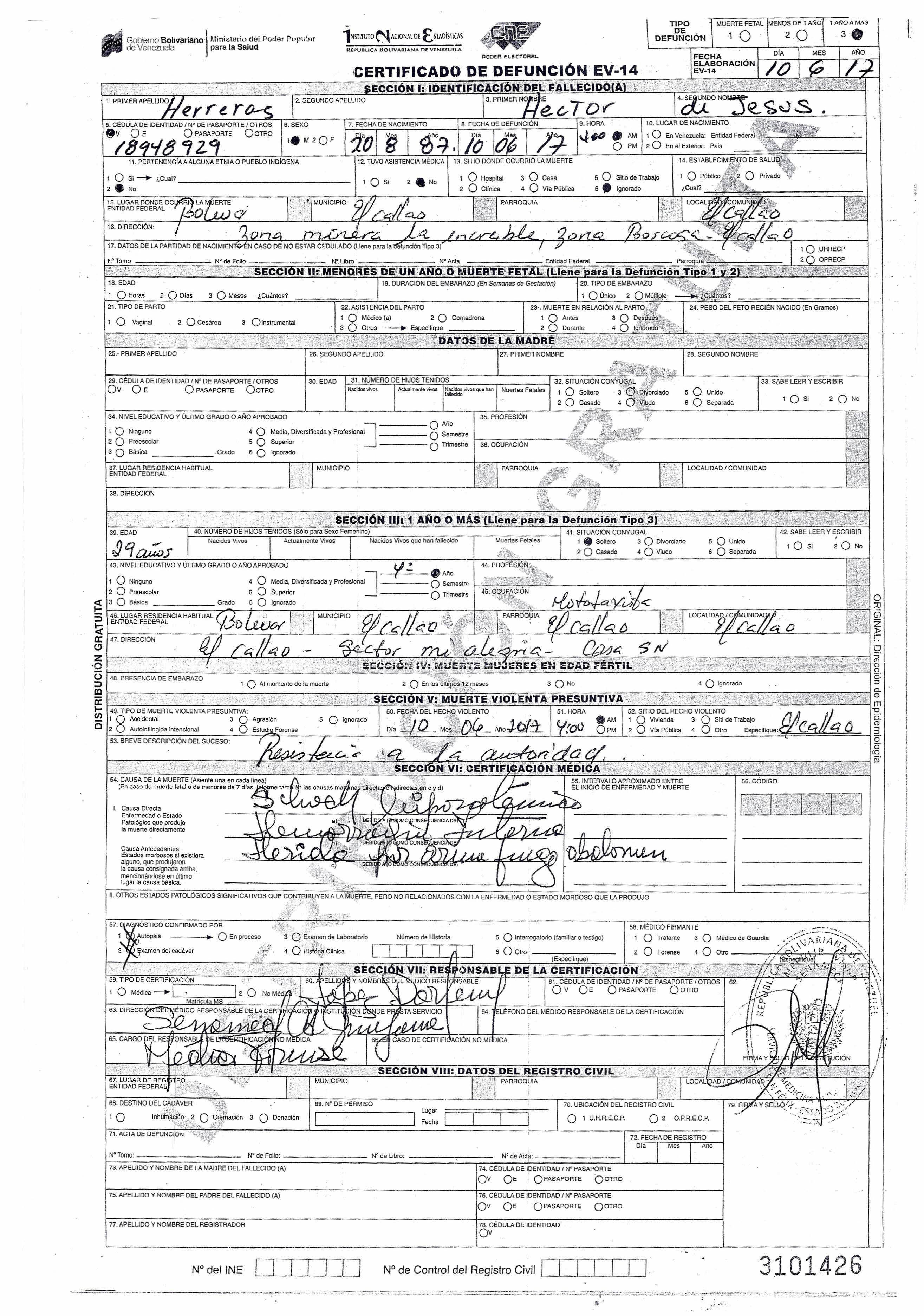

From the house of Héctor Jesús Herrera, who died in June 2017 during an OLP in Loma Linda, south of Bolívar, members of the Intelligence and Strategy Division of the Bolívar State Police (DIEPEB) took televisions, cell phones and video game consoles. Herrera had a small provision store and they took food for sale and the cash that had been collected the previous day. They also went into nearby homes, where they mistreated women and stole what they could.

In Barlovento, OLP officers have also burned the homes of suspected criminals after executing them. A resident of Río Chico, in the state of Miranda, who asked not to be identified, has witnessed several procedures. “After killing the boys, they steal things of value, like plasma TVs and air conditioners, and burn the houses. They carry gasoline for this,” he said.

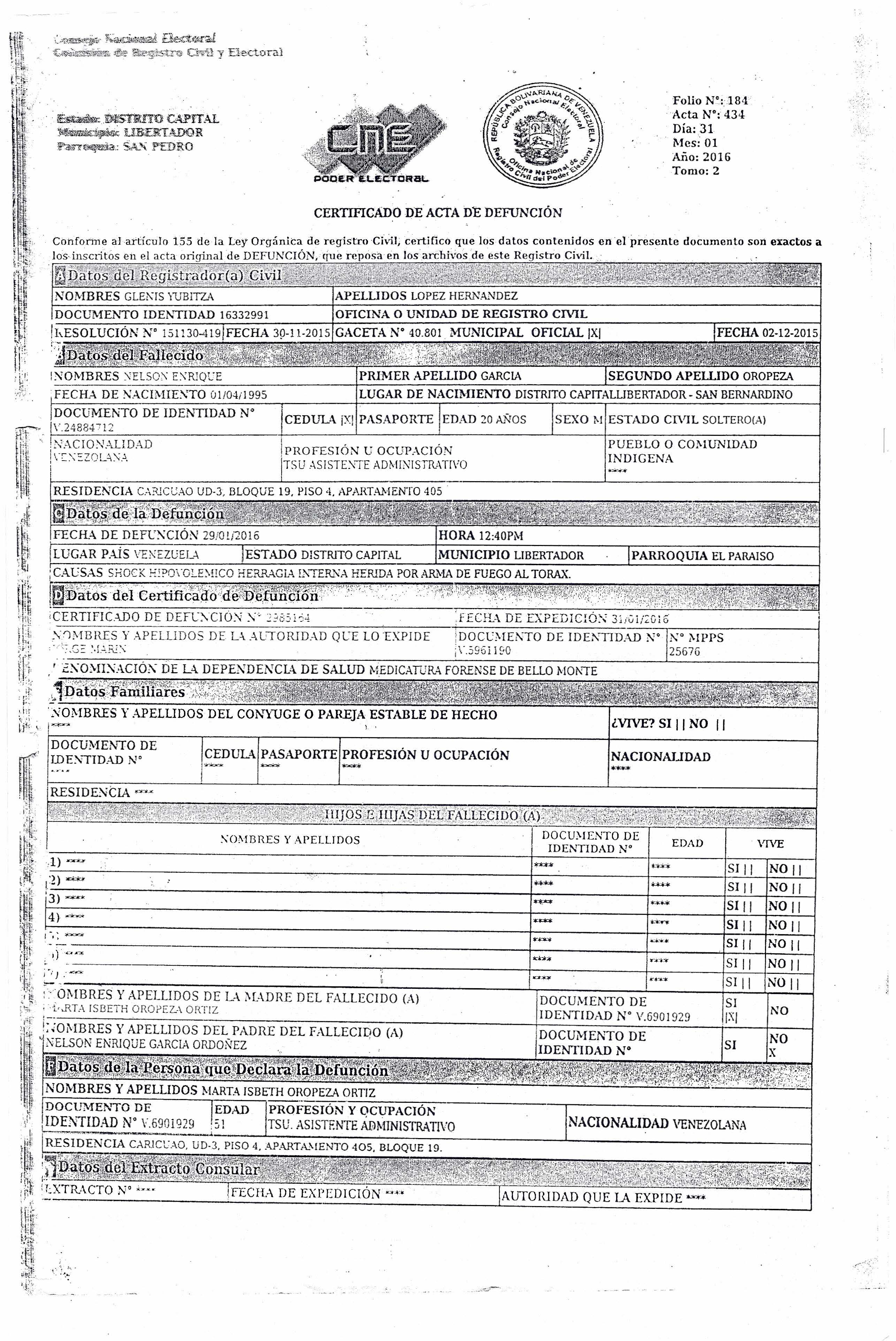

Martha Oropeza was not in her apartment when the OLP arrived at her building, in Caricuao, Caracas, and took it over for 9 hours. Officers broke in, killed her 21-year-old son, Nelson García Oropeza, and searched the place from top to bottom. “They stole everything. They stole his clothes, the cell phones that I had there, perfumes, tape recorders, cameras, money that I had”. When she returned, she saw one policeman in the parking lot of the building testing her car keys on other vehicles and activating the alarm to check if the car was there. She had to show him the ownership documents of the car to have her keys back.

“With everything and the fact that they are surrendering … they kill them”

Although article 47 of the Constitution says that a warrant is required and “the dignity of the human being” is respected during the raids, the violation of private property has remained constant in every procedure of the so-called Operation to Liberate and Protect the People.

“During President Maduro’s first addresses, he insisted that the OLP was intended to punish criminals as much as possible. It seems to be a state policy aimed at breaking into the houses of poor people, destroying and stealing what they want and mistreating those who live there,” said Ronnie Boquier, lawyer of the Committee of Relatives of Victims of the Caracazo (COFAVIC).

Without justice

One of the particularities of the OLPs, which sets them apart from other police procedures, is that they were a series of mixed operations involving officers from different security forces: the Bolivarian National Police (PNB), the PNB’s Special Actions Force (FAES), corps of the Bureau for Scientific, Criminal, and Forensic Investigations (CICPC), the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN), Bolivarian National Guard (GNB), the GNB’s National Anti-Extortion and Kidnapping Command (CONAS), the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence ( DGCIM), municipal police and, occasionally, the Army.

NGO representatives and experts in citizen security, human rights and access to justice agreed that this type of combined actions prevented the individualization of responsibilities when crimes such as executions, mistreatment or robbery were committed.

The efforts to seek justice for the OLP victims face many challenges. Liliana Ortega, director of COFAVIC identified some. “The chances of an independent investigation are very remote due to the mechanisms of impunity that are common in every procedure. Those who investigate are from the CICPC which has, in many occasions, been part of the OLPs”.

After an OLP was carried out, there was no one to report where the bodies were taken, or where they had sent the detainees. The formula forced family members into a pilgrimage through hospitals and morgues looking for their dead, and through police stations, checkpoints and police headquarters, looking for the detainees.

Security forces that participated in the OLP

The OLP in Ciudad Caribia on June 30, 2016 was over after 11 in the morning. The family of Rodolfo Manrique prepared to go out to find an answer about his whereabouts, as the uniformed had taken him from his bed more than 6 hours earlier. They were planning to go to prisons and hospitals without knowing that the young man, father of four children, had been executed and that his body had been thrown on a pick-up truck that collected bodies throughout the urbanization. Before noon, a neighbor contacted the victim’s mother to tell her that her son’s body was at the Bello Monte morgue.

The pain of losing a family member in the context of a terrifying and irregular procedure is compounded by the uncertainty of not knowing what happened to the person who was arrested alive. To find the body of his son, Asdrúbal Granados had to go to five police stations throughout Caracas. He lives on 23 de Enero, where his son Yanderson Granados Padrón, 25 years old, was arrested by the OLP on October 6, 2016.

“They were commenting … this one took it, this one killed him, this one saved himself.”

“They told me that the OLP had arrested him, so we went to the delegations looking for him. First we went to the CICPC in Propatria and they told us they had not been involved. Then to the PNB in Catia, from there to the PNB of La Quebradita in San Martín, then to the PNB of Maripérez and finally to San Bernardino. There, on television, we learned that my son was dead.”

Something similar happened to Héctor Jesús Herrera, killed in El Callao. His mother saw him badly beaten but alive when he was taken from their house. He was thrown in the back of a rustic vehicle with his hands and legs tied with sheets. They went looking at nearby police checkpoints shortly after the operation was over, with no results. So the family members began to check if he had been transferred to a health center. And so it happened: he had been left dead at Juan Germán Roscio Social Security hospital in El Callao. The official version claimed that he was a member of the band of “El Ángelo” and that, instead of being taken from his home, he had fallen during a confrontation with the police at La Increíble mine.

“The OLPs have been carried out in violation of every police action rules contemplated in article 119 of the Organic Code of Criminal Procedure (COPP), namely: unlawful use of the force; weapons against the unarmed; they have infringed torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading punishments and have not informed the detainees about their rights. Regarding detention, they have proceeded contrary to law: they don’t identify themselves as agents of authority (they are dressed in black, with their faces covered, without a badge with their name and surname) and, in many cases, they don’t verify if the arrested person is the same of the arrest warrant, because they don’t even have one. The death penalty is not contemplated in any way in the Venezuelan legislation,” said Luis Izquiel, criminologist and former prosecutor of the Attorney-General’s Office.

That these cases are investigated, that it is proved that victims were executed and those responsible are punished, is almost a utopian scenario. Ronnie Boquier, lawyer at COFAVIC, explains that the CICPC (which is in charge of the investigations, under the direction of the Public Ministry) hinders the probability of solving the crimes. “There are cases that happened more than three months ago and the file has not reached the Public Ministry. Retaining records at the CICPC is a pattern. There is a denial of access to the file. So we don’t know what it says about the crime scene, autopsy and ballistics. Those are very important evidence to clarify the case.”

Boquier, who represents relatives of victims of the executions, says that they have sometimes had to go to the Attorney-General’s Office to demand that they request the files from the CICPC. However, the inspectors of the scientific police do not respond to their requests, without this entailing any consequences or sanctions. “After a year of the homicide some files have not yet reached the Prosecutor’s Office. We have met with the Director of the CICPC General Inspectorate and at the time, the Director of Fundamental Rights in the Attorney General’s office. But the situation persists.”

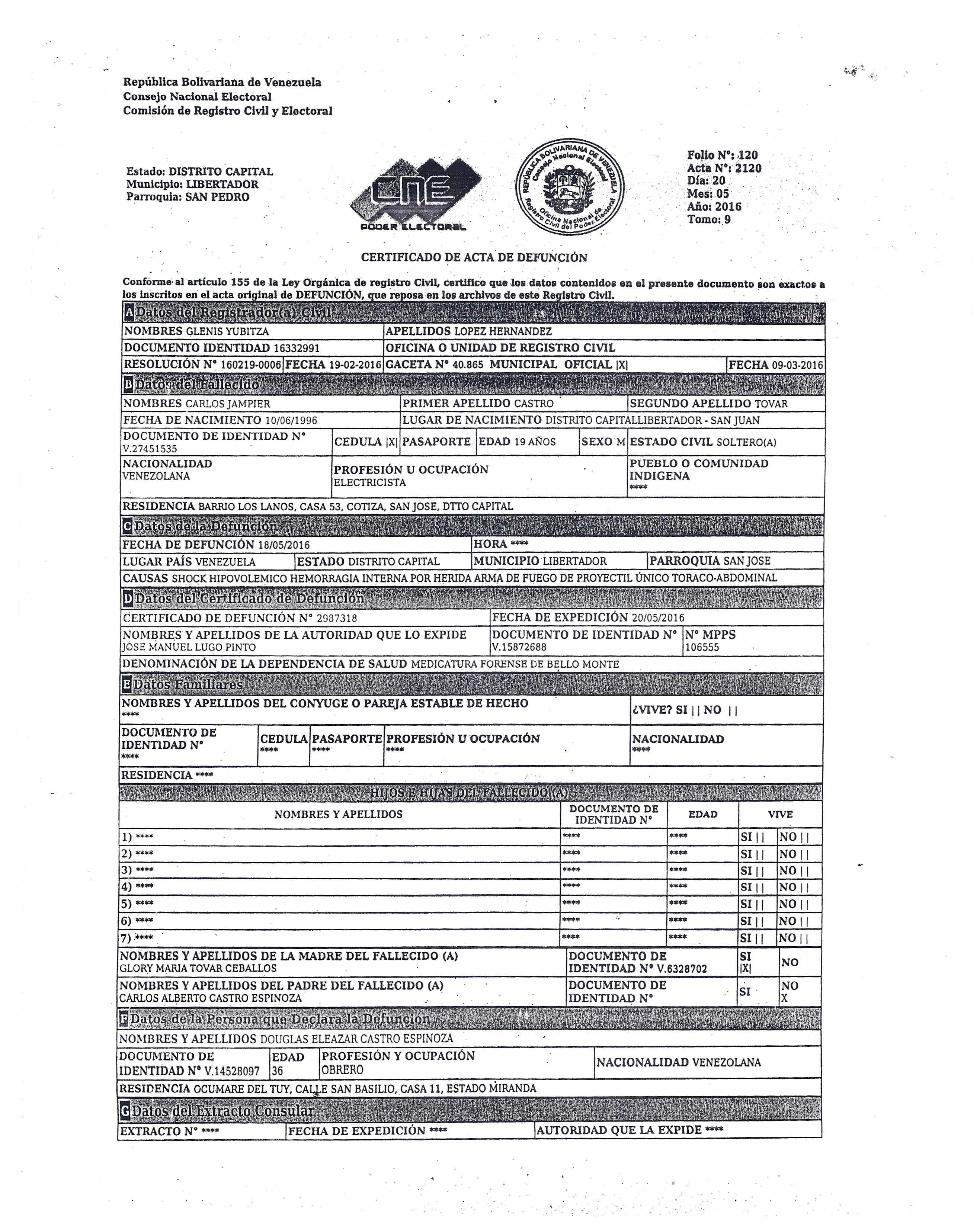

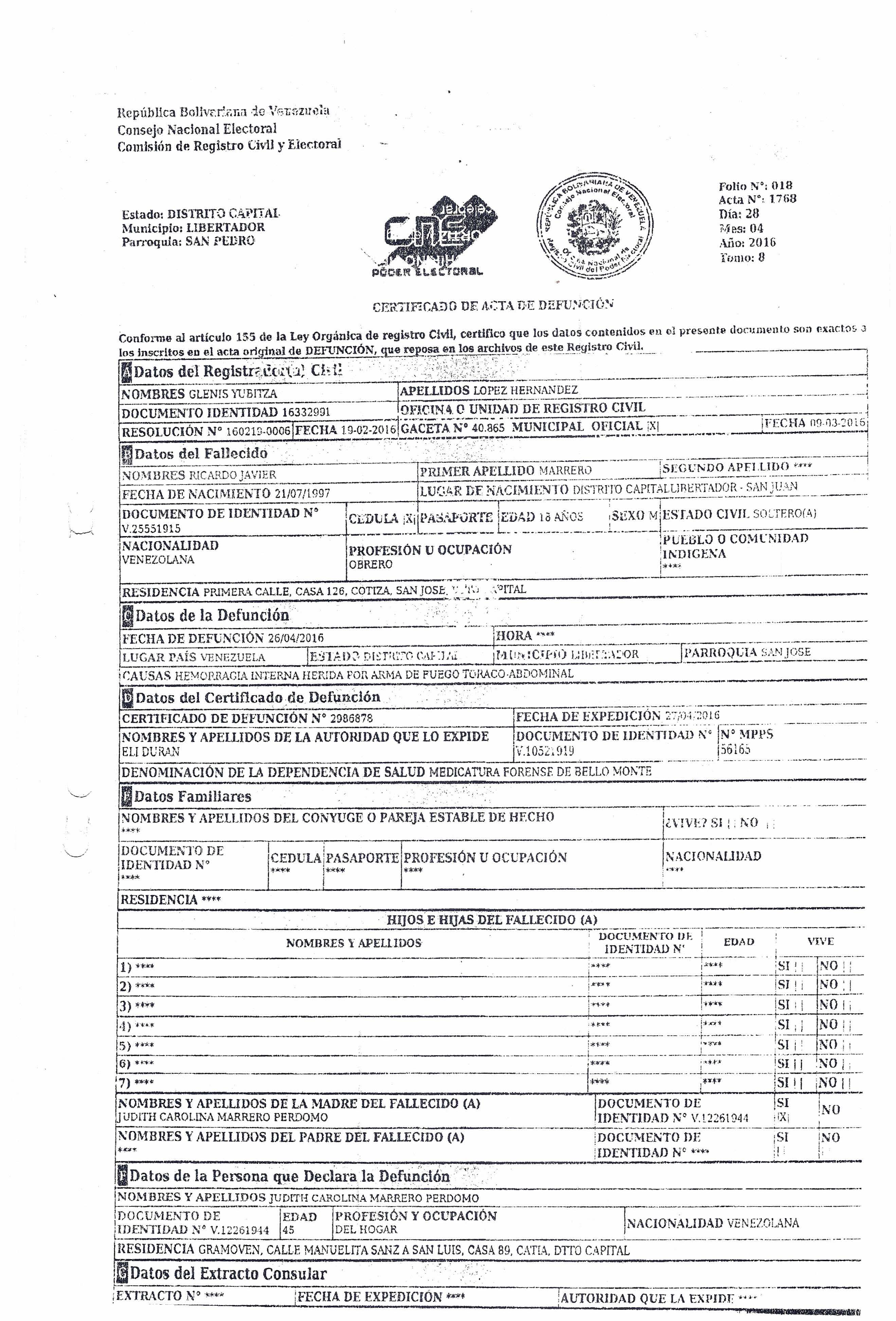

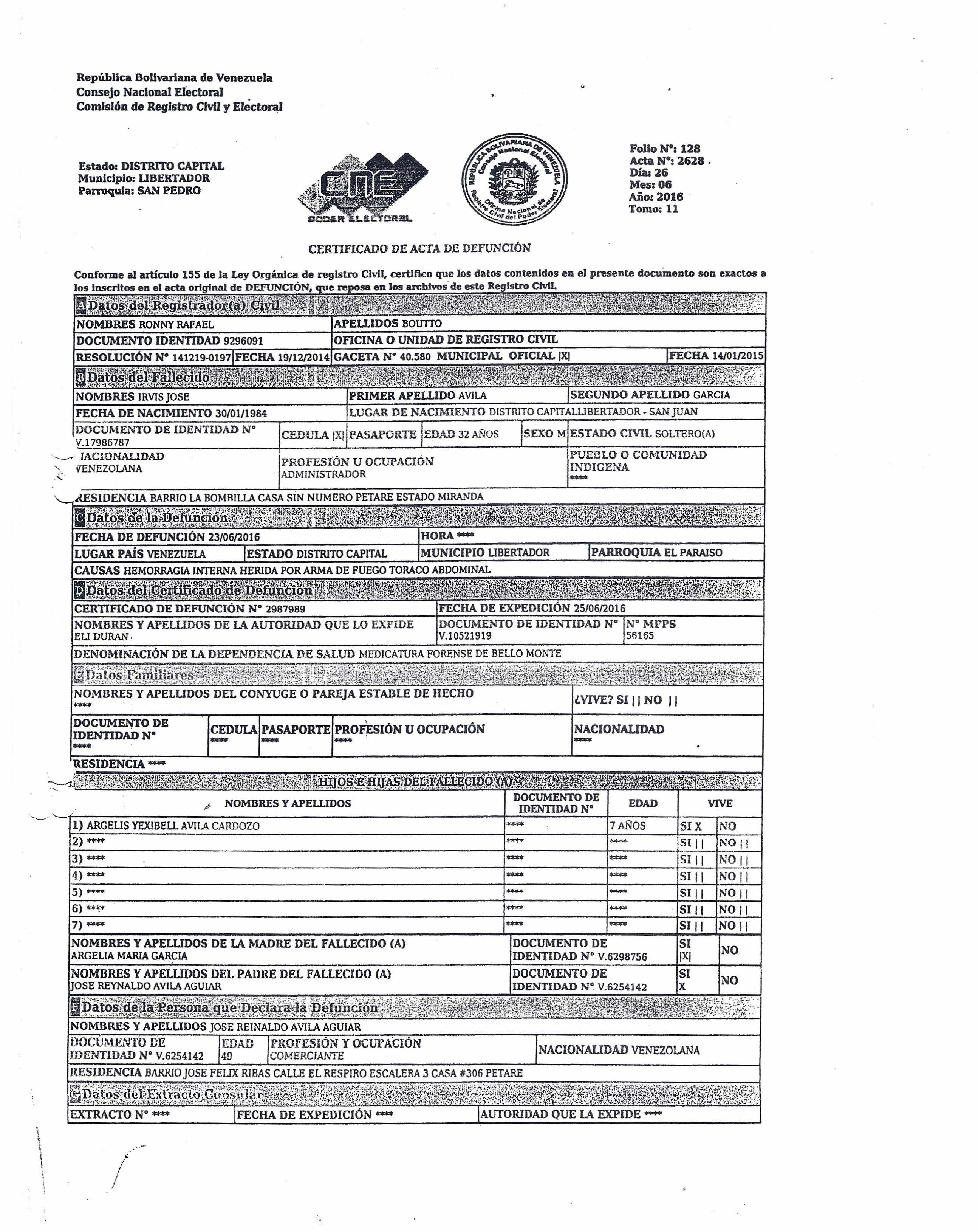

In order to carry out this investigation, the family members of the victims were asked for the autopsies and death certificates of their dead relatives during the OLPs, and although there were cases of 2015 and 2016 among the interviewees, none had had access to those documents. Most of them only had a death certificate issued by the town’s morgue. This document did not describe in detail the causes of death. It only specified whether the corpse had a firearm wound and a brief description of its effect: “Internal bleeding. Thoracoabdominal firearm wound or hypovolemic shock”, were the most common explanations.

The death records were the only documents received by the relatives of the OLP victims. In the “Cause of Death” section, almost every document says: hypovolemic shock, internal bleeding, gunshot wound to the abdomen or thorax. The families did not have access to the autopsy results.

Source: Organization of the relatives of victims of human rights violations (Orfavideh)

“They don’t want justice to be done. The victims get tired. They live in grief and then fall into a system that revictimizes them,” says Boquier. More than 95 percent of the complaints that COFAVIC has received are at the investigation stage and many have been two to four years in that state. And this is the case of the families that have decided to file a complaint. In most cases, they receive threats and prefer to remain silent. ■