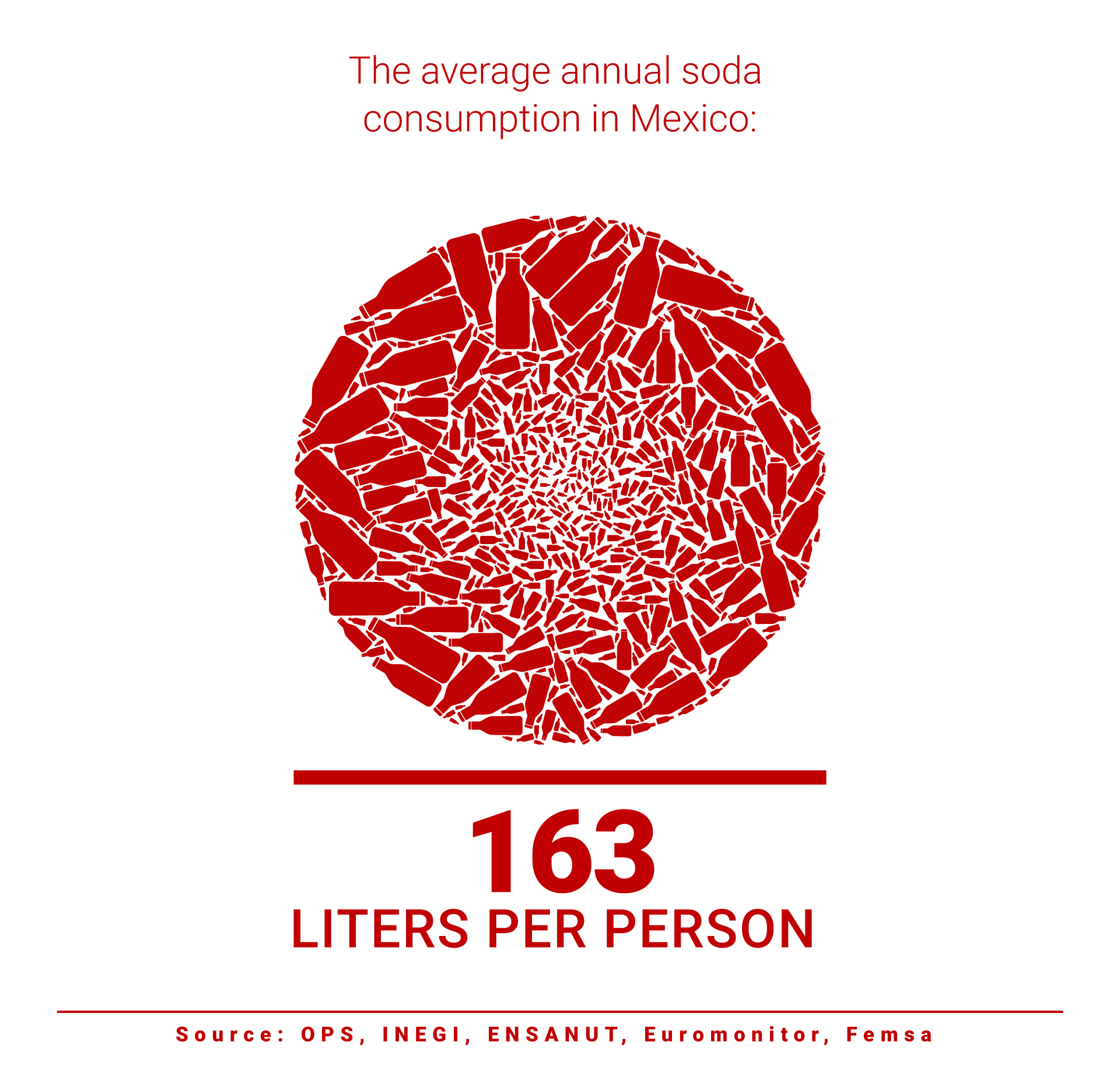

Mexico is the main sugar-sweetened beverages consumer in the world, with an annual average consumption of 163 liters per inhabitant, according to the National Public Health Institute. One of the reasons is that different federal administrations have allowed these products to be distributed in schools, hospitals and sporting events, among others, and have failed to adequately inform the population about the health risks in their consumption.

The World Health Organization recommends the reduction of the daily intake of free sugars to less than 10% of a person’s total energy intake; nevertheless, in Mexico between 66 and 91% of the population consumes a far higher percentage through added sugars. Sugar-sweetened beverages are responsible for, at least, 70% of that overconsumption. As a consequence, 7% of the annual death toll in adults is attributed to these products, according to the National Health Public Institute.

Concerned over this growing public health problem, the Peña Nieto administration implemented the National Strategy for Obesity and Diabetes Prevention and Control (see here). The program was fronted by the then incumbent Secretary of Health, Mercedes Juan López. As part of the work plan, she announced in 2015 that a special labeling for ultra processed foods and drinks would be implemented.

Nevertheless, the World Health Organization recommended not to apply such labeling, as it directly contradicted the government’s strategy as it posed “the risk of misinformation to consumers”; the tagging promoted the consumption of added sugars, even though the human body does not really require them. “In Mexico, one can find these types of sugars in soft drinks, bottled “fruit” juices and fruit premixes”, reads a letter sent by the WHO to the Secretary. “Those products directly cause obesity and health damage”. The Organization even offered technical support by specialists for the design of said labels.

Mercedes Juan rejected the proposition and opted to commission two lawyers and an environmental sciences teacher to design the label, all of them COFEPRIS employees; the main responsible was Patricio Caso Prado, who at the time was a legal adviser for said federal dependency.

The labeling only pointed out the amount of total sugars with no further explanations, which could of course confuse the consuming population as Javier Zúñiga, lawyer for El Poder del Consumidor (The Consumer’s Power), explains. In his opinion, this can particularly benefit companies like Coca Cola, as it allows them to report a lesser percentage of sugar than their products really contain.

The National Public Health Institute also insisted on not going forward with the labeling. “We were vocal about the fact that it was a system created by their same industry, based on deceptive criteria, difficult to understand clearly, and that had proven no impact whatsoever over nutrition and did not help the consumers to choose wisely; the measure could not protect people who consumed less healthy foods”, says Simón Barquera, head of the Nutrition Policies and Programs Investigation Department of the Institute.

But, even in the face of criticism, Patricio Caso defended the labels, and COFEPRIS dismissed guidelines by the World Health Organization, as Barquera points out. Furthermore, nutrition academics were excluded from the meetings where the norm and labeling were discussed and only people belonging to soft drinks companies were allowed.

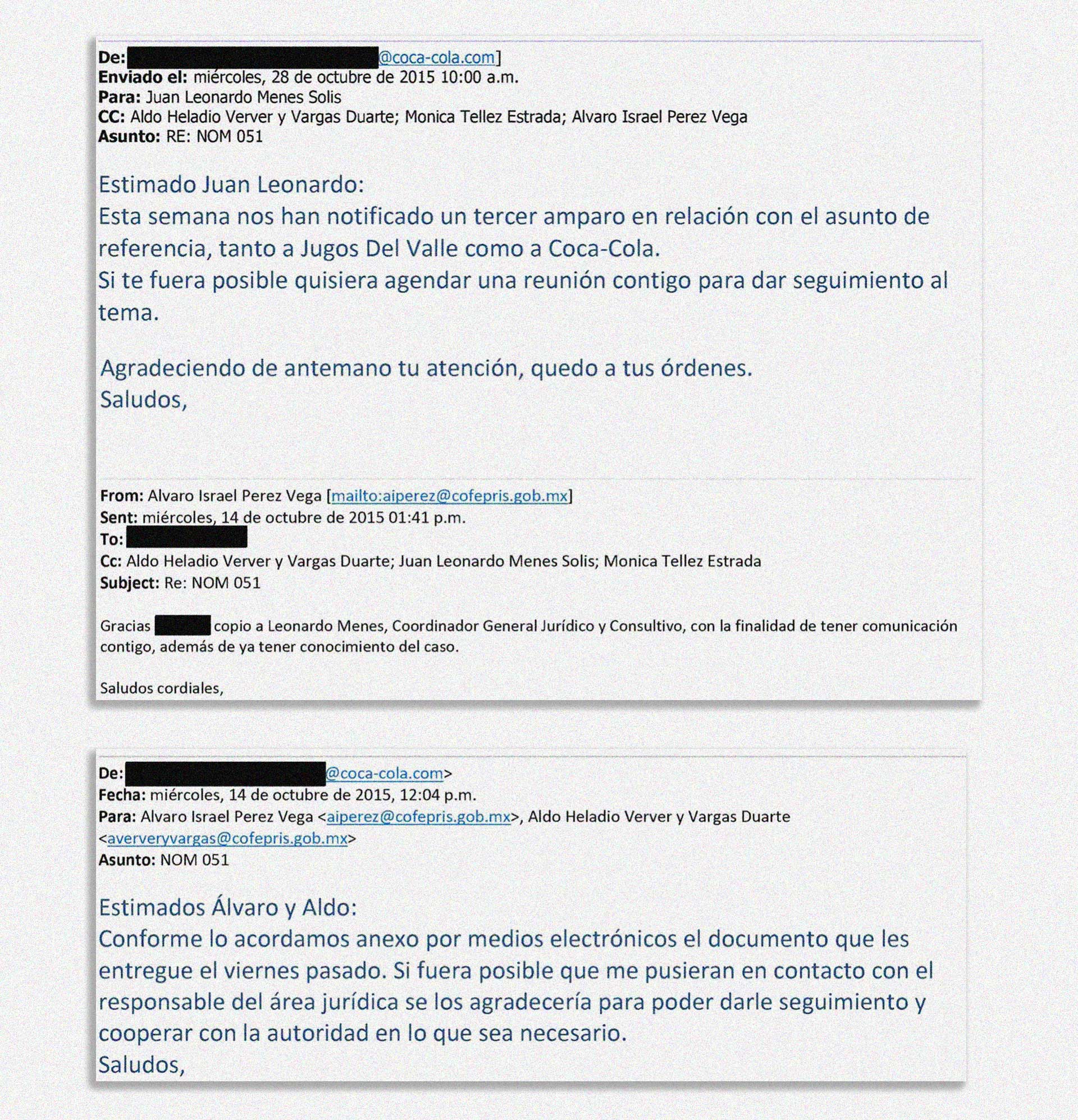

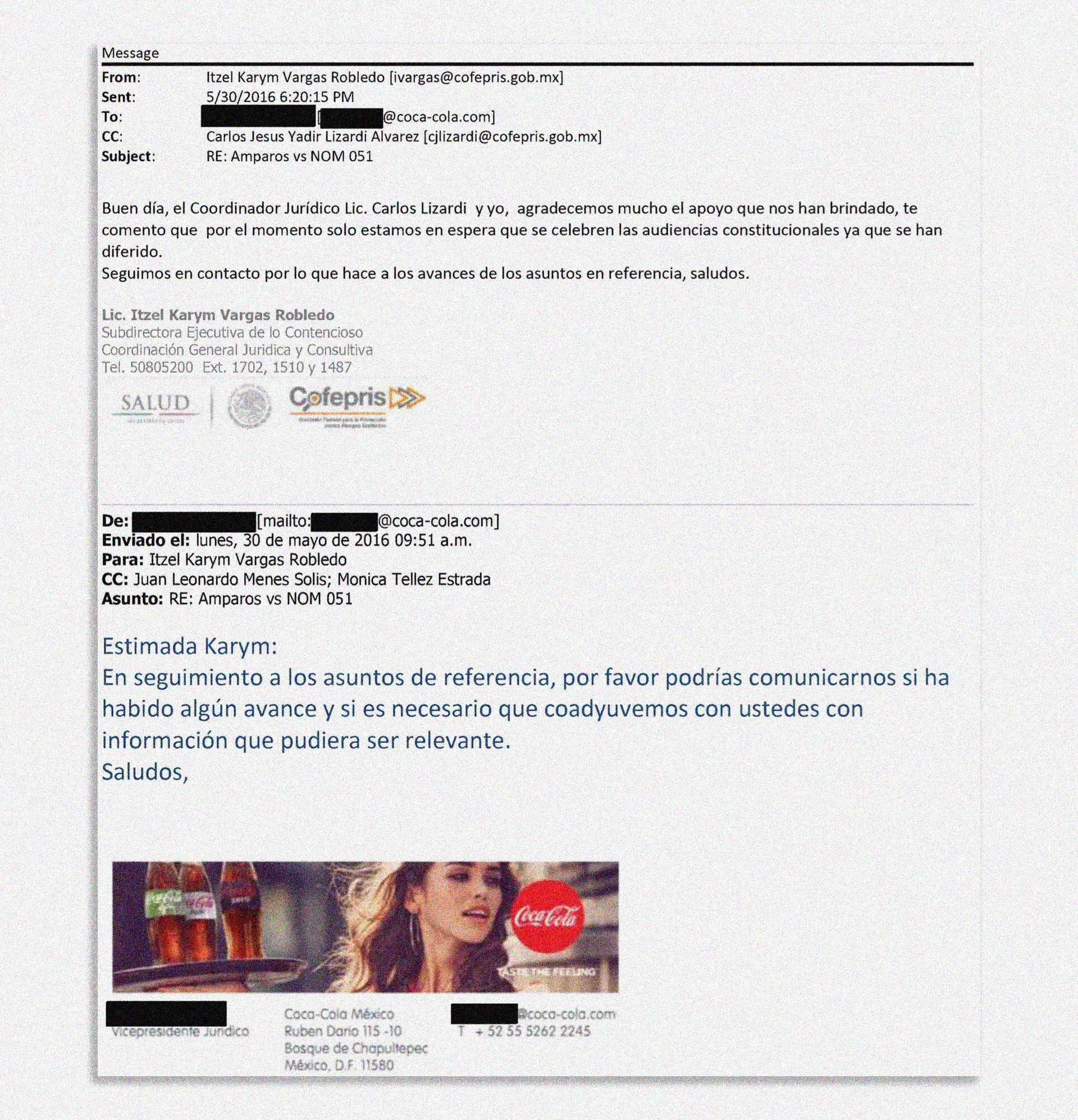

Coca Cola’s intrusion in the label design was documented in a series of emails exchanged by COFEPRIS officers and company executives in May 2016. The subject of those emails was “Appeals against NOM 051”, the name of the official Mexican norm that establishes all food and drink labels specifications.

These emails were obtained by El Poder del Consumidor under the statute of the Foreign Legal Assistance, a resource that allows to request data and testimonies from federal courts in the United States as long as those cases involve American persons and enterprises, and only if the information is deemed relevant for a foreign trial process.

In the messages, the legal vice president of Coca Cola Mexico (whose name is suppressed from the documents) contacts Itzel Karim Vargas Robledo, legal subdirector at COFEPRIS. The former asks the latter if there were any advances in the “reference business” so as to “help with any relevant information”.

The officer replies hours later and greatly thanks him “for the support given” and informs that they have to wait for the constitutional hearings to take place. Reunions to discuss NOM 051 (on foods and non-alcoholic drinks) among executives are also mentioned in those messages.

Some emails are directed to Juan Leonardo Meses Solís, who then was general legal and consultative coordinator for COFEPRIS; he was the other responsible lawyer, along with Patricio Caso, in the label design discussed above. In one of those mails, a Coca Cola employee requests a reunion to “follow up” the legal protection topic, as a third notification for legal action was received by Jugos Del Valle (a Mexican bottled and canned juices company) and by the soft drinks corporation.

The participation of Mónica Téllez Estrada can be proven in other messages. She was, until recently, the general legal and consultative coordinator for COFEPRIS and the entity’s Transparency Committee president.

For this research, a copy of the NOM 051 modifications file was requested, but COFEPRIS assures they are not in its possession. It has not been possible either to know more about conversations between COFEPRIS officers and Coca Cola employees or to read the meetings log; the institution denied having this information, which was requested via the National Transparency Platform.

In 2019 the Andrés Manuel López Obrador administration suppressed the Patricio Caso-designed label on foods and drinks. A new warning labeling was proposed, one that follows the Chilean and Peruvian models; it was fully supported by UNICEF, the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization, as well as food security advocates and promoters. A first study by the National Public Health Institute estimates that this could reduce obesity cases in around 1.3 million and save 1.8 billion dollars in ailment costs.

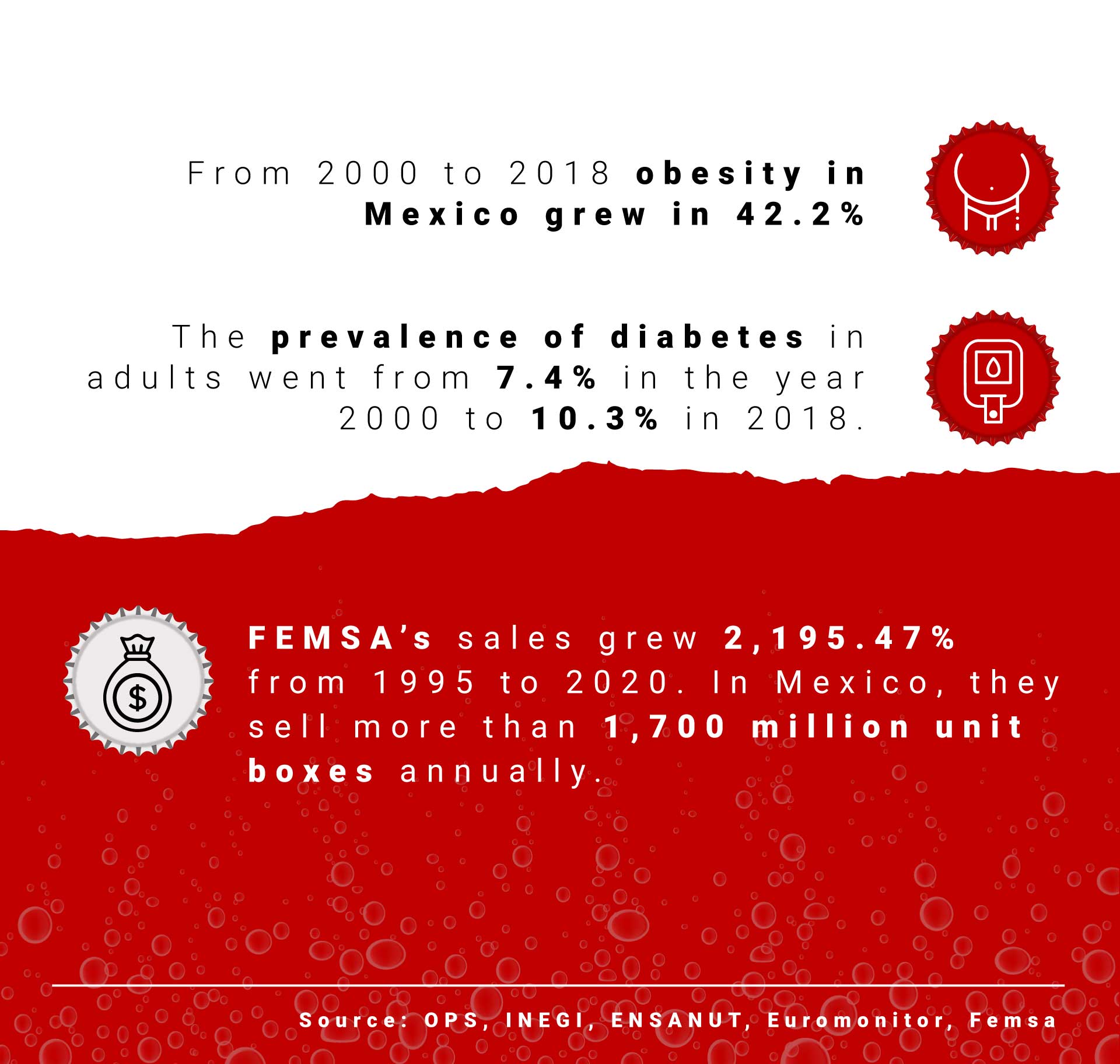

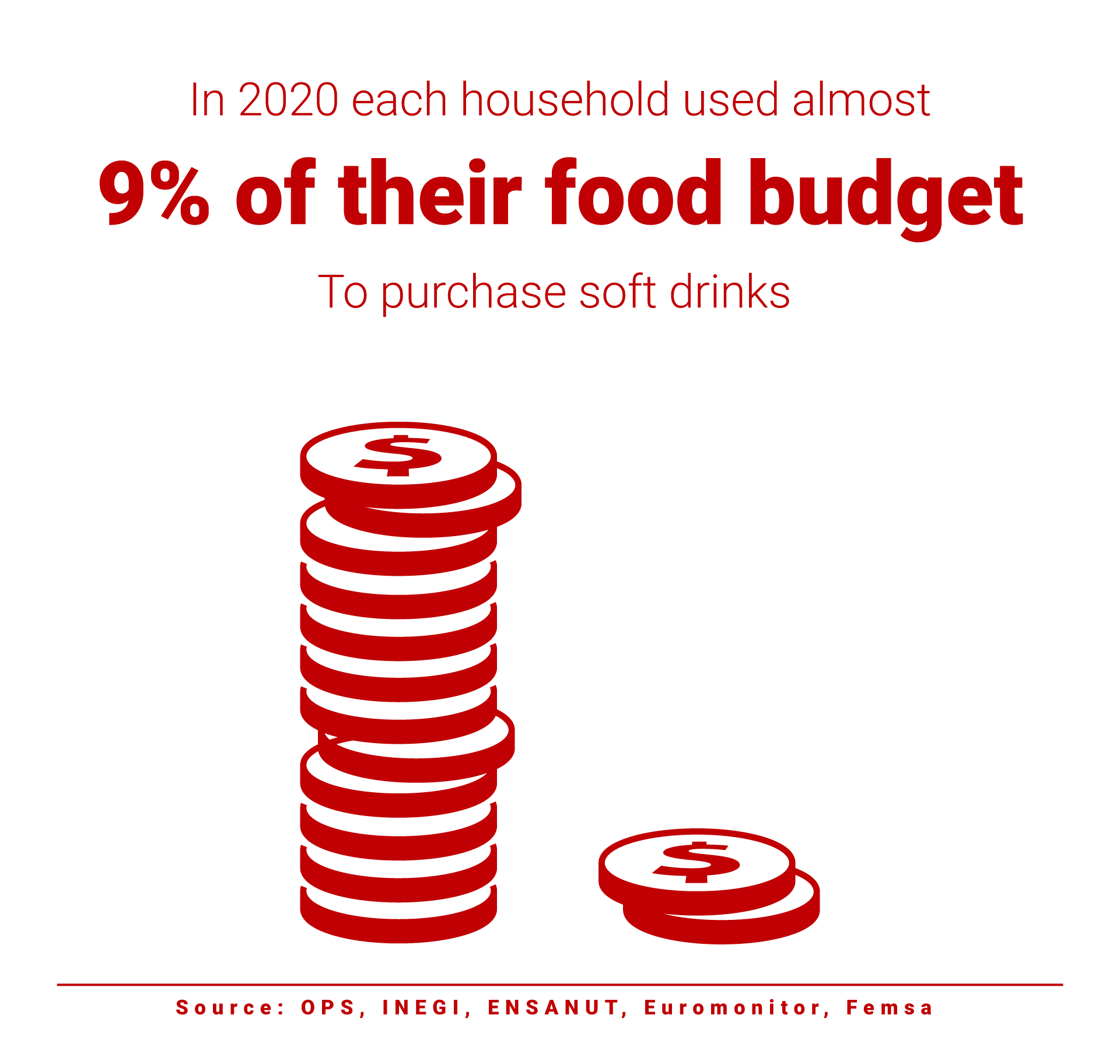

Another measure awaiting implementation is the taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages, aiming to reduce their nocive effects on the Mexican people’s health. The Vicente Fox administration (2000-2006) had first suggested this, but the proposal was repealed by the president himself. During this period, the prevalence of obesity increased 1% every year.

The Peña Nieto administration achieved in approving a tax of $1 Mexican peso for each sugar-sweetened beverage liter, but it was just an economic measure, taken to compensate for the decline of oil prices in 2014. Academics and activists demanded to destine the money levied to the prevention and attention of obesity and diabetes; the government used the money for other undisclosed means.

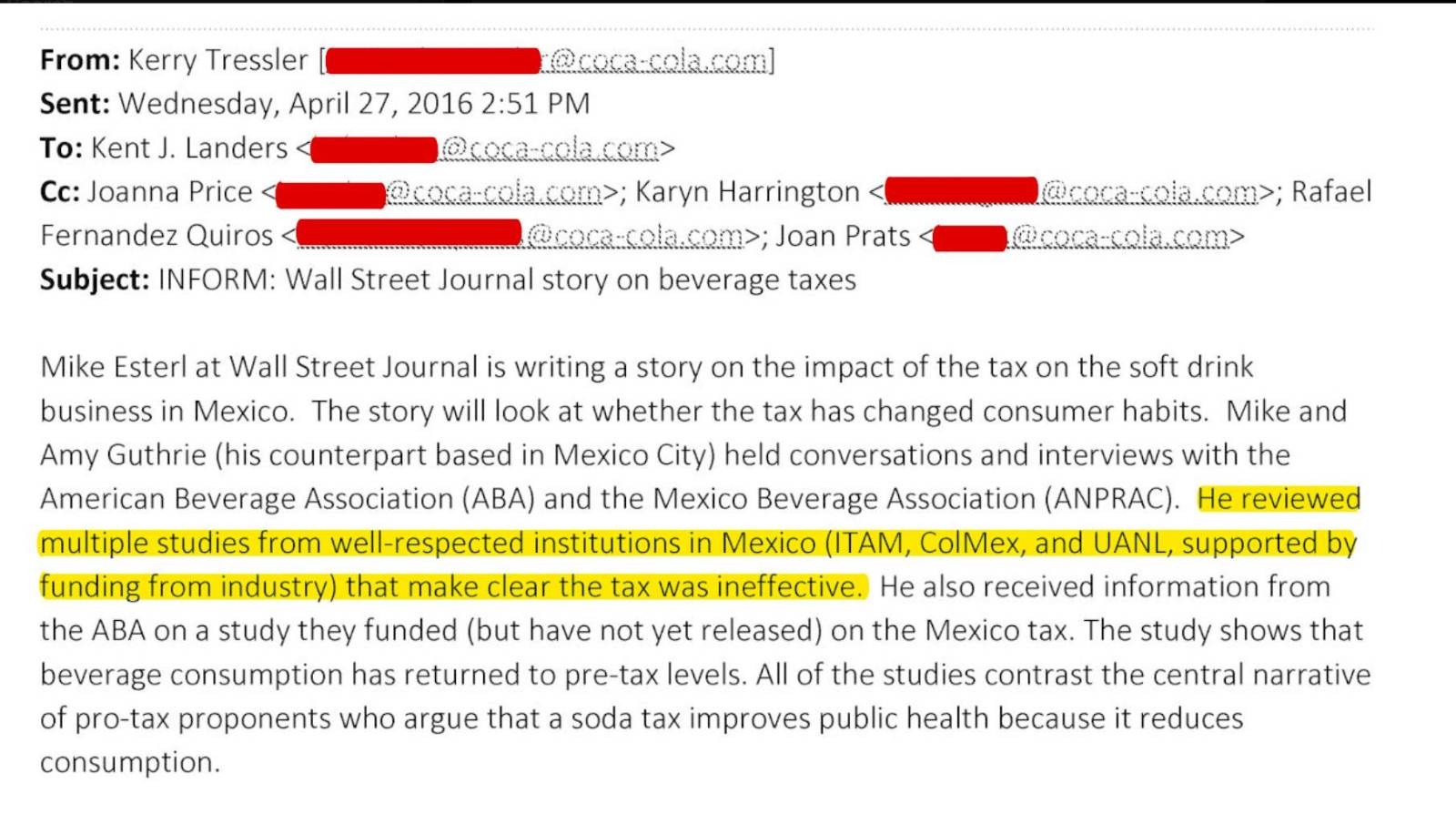

To delegitimize the impost, the National Association of Producers of Soft Drinks and Carbonated Waters published three researches by the Nuevo León Autonomous University, the College of Mexico and the Technological Autonomous Institute of Mexico. The arguments were that the sugar-sweetened beverages consumption was not the main cause for obesity in the country, that there were no “conclusive evidences of the effectiveness of taxation as an instrument for changing the patterns of consumption of health related goods” and that taxes “did not produce any effect on the total caloric intake”.

In an internal email sent 27 April 2016 Kerry Tresler, spokesperson for the Coca Cola Company, states that the researches performed by these three institutions were possible thanks to soft drinks industry funding. Besides, Coca Cola leaked the papers to international press outlets as part of a campaign to discourage taxing on their beverages in other countries, as evidenced in other internal corporate emails made public by the University of California in San Francisco.

Detail of the internal mail of Coca Cola made public by the University of California in San Francisco

“What those documents really reveal is the concerns that Coca Cola executives had about the diffusion of soda taxation beyond Mexico and how to stifle that diffusion. The concern was not just with the Mexican market, but also about other markets in Latin America doing taxation”, says Laura Schmidt, professor at the UCSF Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy studies, who along with a special team did an analysis of said communications.

The topic reached a high level reunion about non-communicable diseases in 2017: “It was the first time that the World Health Organization and other stakeholders in the United Nations started to really talk seriously about taxation as a strategy for obesity and diabetes prevention” states Schmidt. “And it was really the research conducted on Mexico that got that conversation going”.

The new labeling and other regulations adopted by the López Obrador administration have not been free of political pressures. For instance, Alliance for Trade Enforcement, a coalition of commercial associations and business groups who lobby to prevent unloyal commercial practices that may damage the United States industry, requested vice president Kamala Harris to intercede in front of López Obrador; they consider that they hold a disadvantaged position within the USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement). Other organizations have accused that commercial treaties are violated through these measures.

For Coca Cola FEMSA, the concerns go beyond the new labeling in foods and drinks as, starting in 2020, Mexico is effectively implementing labeling that affects all of their products, except for pure bottled water.

For instance, this year, the Mexican state of Oaxaca reformed a law that prohibits the distribution, donation, gift, sale and supply of any drinks with added sugars and any packaged foods with high caloric contents to underage minors; it also forbids the sale and supply of these products in schools, hospitals and clinics. At the same time, the state of Tabasco prohibited sugar-sweetened beverages advertising near schools and clinics and increased in 25% the collection of advertising rights.

In reply, Coca Cola FEMSA filed a series of appeals against all these measures, and in their annual 2020 report indicated that, if their legal resource did not succeed, said reforms could have “an adverse effect” on their Mexican operation results. In their 2020 report, the Coca Cola Company considered local regulations and warning labels as a risk factor for their operations; the firm also admitted “a 4% decrease in the volume of product boxes per business unit in Mexico”.

FEMSA did not reply to our requests for an interview.