By Grisha Vera

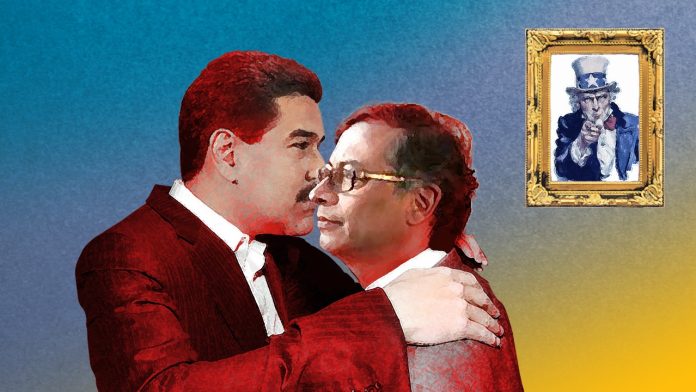

Last week’s move by Gustavo Petro to reestablish ties with the government of Nicolas Maduro entailed a radical swerve for Colombia’s foreign policy. Venezuela and Colombia’s pending issues in terms of security and trade led many –the moderate ones– to believe that the decision was long overdue.

At the time, diplomatic ties were severed because Colombia’s former President questioned the Venezuelan elections in 2019, deeming the process as fraudulent and refusing to acknowledge the legitimacy of Nicolas Maduro. The decision, which was backed by fifty more countries, was meant to isolate the current government and oust it. But the strategy backfired and, nowadays, Maduro has gained more recognition and Duque’s term has ended.

Petro played his hand. His first decisions pertaining to foreign policy have aligned him with the leftist governments of Latin America (whose presence is mounting) and that fact could distance Colombia from Washington, its historical ally. In particular, if Republicans win the senate elections in November and attain greater influence in terms of the United States’ ties with its neighbors.

But it would be naive to believe that Latin America’s current leftist block is as cohesive as it was decades ago. Adam Isacson, Director for Defense Foresight at the Washington Office on Latin America, points out significant differences: “There is no Hugo Chavez this time around. There is no overly charismatic president with lots of resources and pushing others. Leftist presidents come in many flavors nowadays. In fact, Gabriel Boric and Daniel Ortega have very little in common, but they may attend the same meetings, we need to get used to that. Yet, they lack the resources that Lula had in Brazil’s boom back in the 2000s, and that Hugo Chavez had in the oil boom in the same decade. They are more varied and also poorer. But they are more than in the past.”

Based on that, Isacson considers that Petro will keep his distance from Maduro, despite acknowledging him. He does not think this recognition will turn into a fraternal embrace because it is driven by pragmatic interest.

🧵#Colombia y #Venezuela: Anuncio de quiénes serán los embajadores (Armando Benedetti designado por #Petro y Felix Plasencia por #Maduro) revela cuál es la perspectiva de ambos gobiernos al tratar de normalizar las relaciones. El intercambio comercial adquiere preferencia. 1/

— Mariano de Alba (@marianodealba) August 12, 2022

Similarly, the American expert explains the United States’ stances: “There are two trends about Venezuela. The first one is very realistic and is followed by Biden’s government and the Democratic Party. It regards that the United States has interests in South America concerning oil and the region’s safety. Thus isolating Venezuela is not convenient, in fact, it strengthens the dictatorship. Communication channels need to be open. They don’t disapprove of what Petro is doing because they are being pragmatic. While Republicans are much more circumspect and prefer to continue isolating Venezuela, they even have the support of some centrist democrats. They intend to keep the isolation, blockage and sanctions policy, disregarding the acknowledgement of Maduro. It’s hard to shift this mentality, and in some cases they consider pragmatism to be a weakness and in others treason.”

That is why Isacson considers November’s senate elections in the United States to be decisive: Republicans may get the majority of Congress. He adds that attention must be paid to the preelection political game with which Democratic candidates intend to hold on to Florida, a State where the votes of Venezuelans, Colombians and nationalized Cubans are mostly Republican and have significant weight. So, most Democrats may adhere to the critical stance regarding Petro’s decisions.

Win-Win

On August 11th, Petro and Maduro appointed their ambassadors, Armando Benedetti and Felix Plasencia, respectively. According to an analysis posted in a Twitter thread by Mariano de Alba, senior advisor of the International Crisis Group NGO, the process of normalizing relations was triggered by a pragmatic issue: trade. According to him: “Benedetti was pivotal for Petro to sit down with the Colombian private sector with the aim of building trust.” He added in his thread: “Encouraging economic recovery is still key for Maduro. Colombia could be relevant in this outlook and Plasencia’s experience includes having seeked opportunities in the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Nigeria and Serbia, and tightening bonds with Russia, Turkey, Iran and China.”

Benedetti immediately responded to his appointment with a tweet assuring that he will surprise Petro reaching the amount of 10 billion dollars in commercial exchange, although he failed to mention the deadline for this achievement.

Presidente @petrogustavo, lo sorprenderé cuando lleguemos a 10 mil mill de dólares en intercambio comercial, cuando beneficiemos a los más de 8 mill de colombianos que viven en la frontera. Ninguna línea imaginaria nos volverá a separar como hermanos.

¡GRACIAS POR SU CONFIANZA!— Armando Benedetti (@AABenedetti) August 12, 2022

German Umaña, Colombia’s Ministry of Trade, seemed more moderate. He explained that trade between both countries is expected to reach 4.5 billion dollars by 2026.

Still, the feeling of euphoria is justified. Following the border closures in 2015 and severed relations in 2019, trade between both nations was reduced to informality. Luis Alberto Russian, President of the Board of Directors of CAVECOL (Camara de Integracion Economica Venezolano Colombiana) illustrates: “The border closed as a result of lack of trust. That border is one of the most active and it has the greatest level of exchange. That has had an important commercial impact because 60% of the trade between both countries moved via these borders as formal trade and through customs. Exports from Venezuela to Peru, Ecuador and most Andean countries used to be by land.”

Russian explains that formalizing the current trade would lead to a significant increase in exchange. It will also entail the recovery of infrastructure in border crossing points, drive employment and tax revenue on both sides. “It is a signal at regional level, it is sending the message that two significant medium-sized economies (in Latin America) will engage in coordinated efforts. (There used to be) a distancing in terms of development models.”

Consequently, Russian is positive that Caracas and Bogota will resume their communication, opening up spaces to discuss gaps and disagreements, and defining opportunities for both nations. However, he emphasizes on the importance of examining and agreeing on the foundations of trade, and addressing ways to solve future conflicts. He warns that for this measure to be successful, it must be sustained in time and generate trust in the business sector.

Essential Topics, Opposed Interests

Colombia and Venezuela reestablished their diplomatic ties but some side-effects remain after years of political divergence. Several leaders of the opposition are exiled in Colombia, e.g., Julio Borges, a member of the Primero Justicia opposing party who has been accused by the Venezuelan government of an alleged assassination attempt against Maduro. On the other hand, Colombia has requested its neighbor to extradite Aida Merlano, a former senator who fled to Venezuela in order to evade a jail conviction of fifteen years for electoral fraud.

Security topics also drive animosity. Venezuela is an ally of Iran, China and Russia –enemy powers of the United States– and it undertakes military exercises with troops of those countries. That is the reason why pragmatism by the United States “will become weak if China or Russia’s presence or influence increases. In fact, one of the reasons why pragmatists choose to carry on the exchange and contact with Maduro and Petro is to try to close spaces for those countries,” Isacson explains.

Tras asunción de Gustavo Petro, #Venezuela anunció que restablecerá“relaciones militares”con #Colombia.

“Dado el nuevo escenario nacional que vive Colombia es momento ya de retomar responsabilidades y de trabajar en conjunto” Min Defensa Vladimir Padrino..https://t.co/HpW4Beh5GX— CarlosSanchezBerzain (@Csanchezberzain) August 10, 2022

Moreover, there is the issue of the presence of Colombian armed groups in at least six states of Venezuela, these groups have turned their backs on the peace process and include dissidences of the FARC, or the ELN (which has not started dialogues). The latter, as Isacson says, is practically a “binational guerrilla” nowadays, so if Petro’s government intends to materialize a policy of total peace, it will need Maduro’s support.

Nevertheless, experts and former presidents have denounced that those groups have the protection of the Chavista government. Isacson concurs: “There is not a lot of political will and I think many officials and members of the ruling class in Venezuela are leveraging the status quo, taking advantage of corruption and collusion. Despite this, there are criminal groups in Venezuelan territory and insecurity is reaching dreadful levels. But now, for the first time, a nicer Colombian government is asking Venezuela to please do something about it. Unlike Uribe or Duque, this government is not rebuking them. A leftist government is asking for help. That may change the whole dynamic.”

Time will tell how pragmatic and new left will Petro act in acknowledging a regime whose democratic credentials have been as dubious as Venezuela’s. Time will also tell how Maduro will act in matters of security that are of interest for Colombia and the United States. Although Maduro’s discourse leans towards the traditional left and he is hugely indebted to China and Russia, he has distanced himself from Russia to explore the opportunity to restart oil negotiations with the United States amidst the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In the end, Maduro himself has proven to be pragmatic.